Why journalist Neerja Chowdhury tells you all that you don’t wanna know about How Prime Ministers Decide!

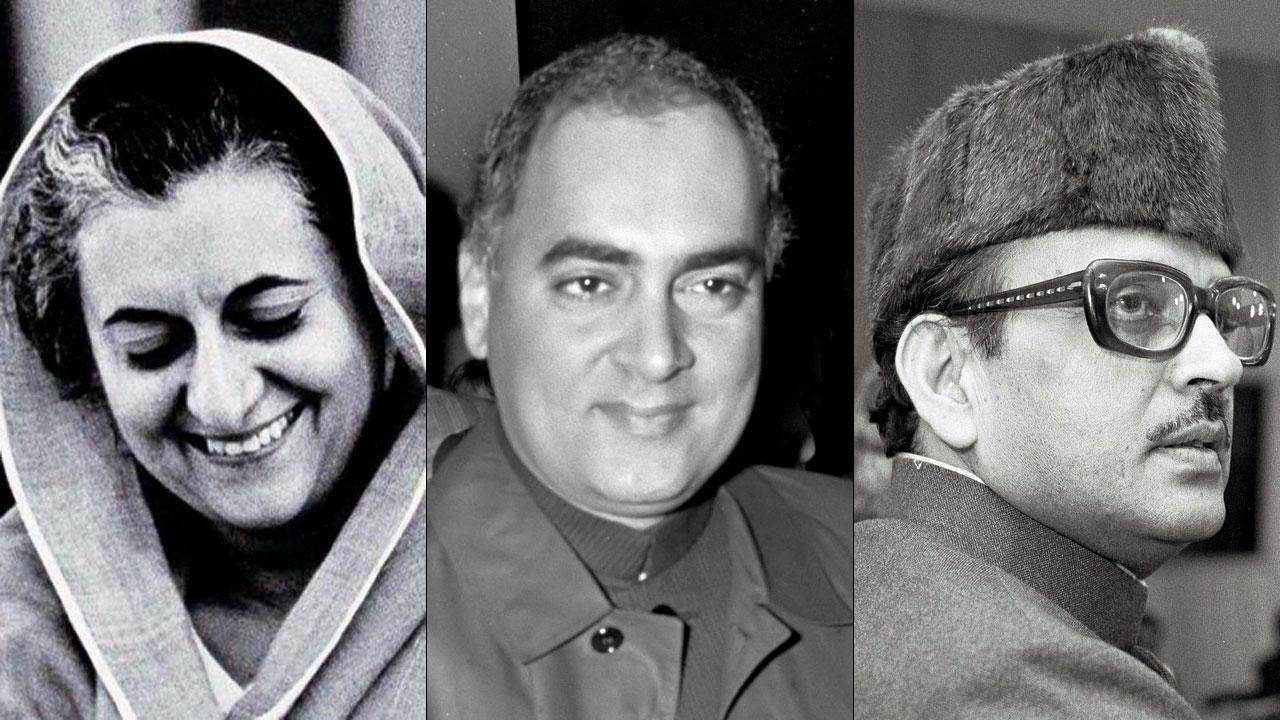

Former Prime Ministers Indira Gandhi, Rajiv Gandhi and V P Singh

An understated reason for Indira Gandhi calling the Emergency in 1975—I learnt from journalist Neerja Chowdhury’s book How Prime Ministers Decide—was to rewrite India’s Constitution.

An understated reason for Indira Gandhi calling the Emergency in 1975—I learnt from journalist Neerja Chowdhury’s book How Prime Ministers Decide—was to rewrite India’s Constitution.

An objective to pause the parliament was apparently to arrange a new Constituent Assembly, that would put in place a presidential form of government in India. Much like the US; only, without the sufficient checks on the US Prez (Senate, Congress, courts, etc).

If you look back at personality cults that have dominated India’s collective, Westminster-style parliamentary system, adopted since independence—doesn’t the role of the Indian PM already seem presidential enough?

Consider the Pokhran nuclear test of 1998, greenlit by PM Atal Bihari Vajpayee. No politician knew about it, until Vajpayee informed them, once the cat had pretty much hopped off the bag.

When Chowdhury met L K Advani, Vajpayee’s number two in cabinet, he sounded melancholic, rather than ecstatic—as he should’ve been, shortly after successful testing of an annihilative bomb, his party was wedded to.

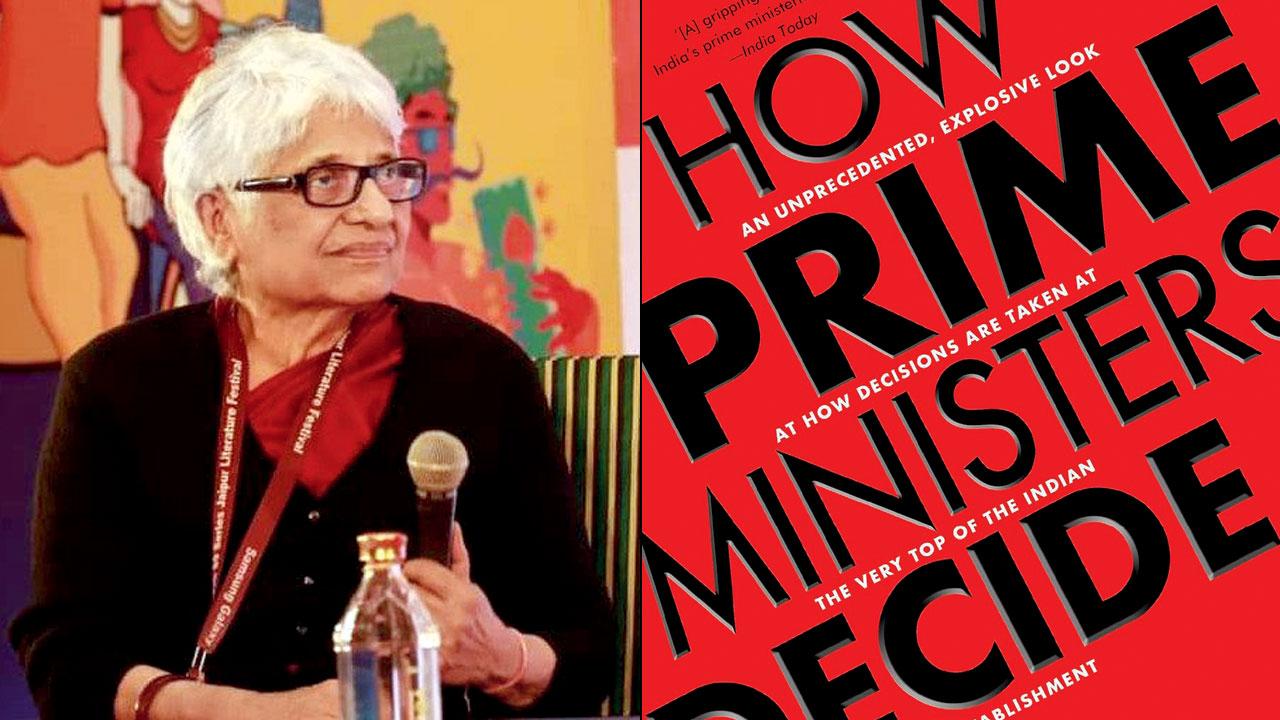

Neerja Chowdhury, veteran journalist and the author of How Prime Ministers Decide

Vajpayee had routinely changed his stance on nuclear testing, throughout his career, as per Chowdhury’s book—so tightly spread over 500 pages, shining a penetrative light on six decisions taken by India’s PMs that could form their legacy.

What they reveal instead is how politics is often triggered by crises so personal, that you’re amazed anybody had the whole country in mind, let alone history, into the future!

Responses are intrinsically to the moment. Decisions remain. Trivia fades over time. For instance, how many will remember the name, Yashpal Kapoor, from PM Indira’s secretariat. He got employed as an election agent on Indira’s Rae Bareilly seat in 1971.

One, Justice Jaganmohan Sinha, at Allahabad High Court, hence, found PM Indira guilty of electoral impropriety—banning her from parliament for six frickin’ years! Pushed to the corner, she imposed Emergency.

Take PM V P Singh, who implemented the Mandal Commission Report in 1990—gathering dust for a decade—because his deputy, Devi Lal, had walked out on him.

Introducing reservations for lower castes in government jobs, before Devi Lal’s anti-VP public rally, gave him just that distraction/upper-hand.

VP knew there would be public opposition to Mandal. He hadn’t anticipated scores of young men dousing themselves in fire. Self-immolation on streets became the rage. Indian politics got centred on caste reservations thereafter.

Or, witness Rajiv Gandhi opening locks of the disputed Babri Masjid in Ayodhya in 1986. This unlocked temple politics in India. The BJP politically skyrocketed from it. Why would Rajiv field so well for his rivals?

Because he’d enacted the Muslim Women’s Bill, right before—effectively denying Muslim divorcees alimony for life; bringing the term ‘minority appeasement’ into popular lexicon.

Liberal Muslims, indeed the women, must’ve felt let down by Rajiv. He simultaneously eyed the Hindu religious votes, therefore, opening up Babri!

Power, the drug, being an end in itself; defined by constant ‘politicking’—leaders looking over head, shoulder, backside, for desperate competitors, making one wonder when any well-meaning work gets done at all. That’s the reason a lot of people identify themselves as ‘apolitical’. What they mean is they aren’t into partisan politics—chiefly, dirty gossip around the not-so-good-looking people. Apathy is also a political act.

Those in politics get immune to bloodstained daggers, I suppose. VP knifed Rajiv’s personal image, dislodged him in 1989. No one from Gandhi family has been a PM since.

When Rajiv’s wife, Sonia, had to cobble together a coalition government in 2004, she approached VP for assistance. Evidently, nothing is permanently personal at the top!

What kinda people become PMs in India? There’ve been 14 since independence. Notable exceptions apart, most seem to be practically single people, either by circumstance or choice. Which is in contrast to western heads of states (say, US, UK), who must parade their spouses to come across to voters as the ‘family type’.

P V Narasimha Rao was a quiet PM, who kept everyone guessing his next Machiavellian move. Contrary to popular perception, Chowdhury, who’s covered politics over four decades, writes, Manmohan Singh had a short temper. The coterie that surround PMs—tantriks, fixers, bureaucrats, businessmen—are inevitably the more interesting characters.

How Prime Ministers Decide is packed with them—as a biography/anthology on contemporary Indian politics, it’s up there with the best I’ve read: Vinay Sitapati’s two books, on Rao, Vajpayee-Advani; Tariq Ali’s The Nehrus and The Gandhis; Ramchandra Guha’s India After Gandhi.

Also, I particularly enjoy non-fiction by journalists because they are, by nature, prone to anecdotes. Whether apocryphal or not, you’re certain the story is from a source no further than a degree of separation from the subject.

My favourite from Chowdhury’s tell-all relates to political rivals, PM Jawaharlal Nehru, and his deputy, Vallabhbhai Patel. Patel wanted a particular candidate as Congress president. Nehru had his own choice. Canvassing for support, Patel went over to Fakhruddin Ali Ahmed (later to become India’s President).

Ahmed told Patel, he’ll go with Nehru. To which, Patel retorted, “Fakhruddin, do exactly what you like. But remember, Jawaharlal can never help a friend, nor ever harm an enemy. I never forget a friend, and never forgive an enemy!”

In her book, Chowdhury doesn’t touch on the current PM, Narendra Modi. You can see why. He’s, of course, yet to be judged, by history.

Mayank Shekhar attempts to make sense of mass culture. He tweets @mayankw14

Send your feedback to mailbag@mid-day.com

The views expressed in this column are the individual’s and don’t represent those of the paper.

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!