A groundbreaking book traces Indian men’s uneasy ties with the home, through figures like Ambedkar, Gandhi, and Premchand

Dr Babasaheb Ambedkar’s grandson Prakash Ambedkar in the study at Rajgruha, Dr Ambedkar’s residence, now his memorial, at Dadar East

![]()

Conduct yourself uprightly. Do not pick fights with anyone. Do not accept anything from anyone for safekeeping. Do not let anyone touch my books.” This was Dr BR Ambedkar writing to his wife Ramabai in July 1920 from London, where he had returned for further studies after a stint at Sydenham College. His Baroda state scholarship had ended, and he was struggling to survive on scarce funds. Ramabai, left behind in Bombay, faced illness, loss, and poverty alone. She pawned her bridal jewellery to support his education and shielded him from the toll of domestic grief, including the deaths of their children. By the time Ambedkar rose to prominence — representing the Depressed Classes at the Round Table Conference in London, becoming a force for Gandhi to reckon with — she herself was seriously ill.

In another letter, written a few months before his marriage to his second wife, Dr Sharda Kabir, an accomplished medical practitioner who was part of the team of doctors who treated Dr Ambedkar in Bombay, he declares honestly: “My companions have to bear the burden of my austerity and asceticism.”

These fragments appear in Men at Home: Imagining Liberation in Colonial and Postcolonial India (publisher Orient BlackSwan) by Gyanendra Pandey, a quietly radical study of Indian men’s private lives — where homes, kitchens, and courtyards become sites of uneasy masculinity. Ambedkar is one of several protagonists, along with Mahatma Gandhi, Rahul Sankrityayan, Premchand, and others, whose greatness rested on the quiet, unpaid labour of wives who remained in the shadows.

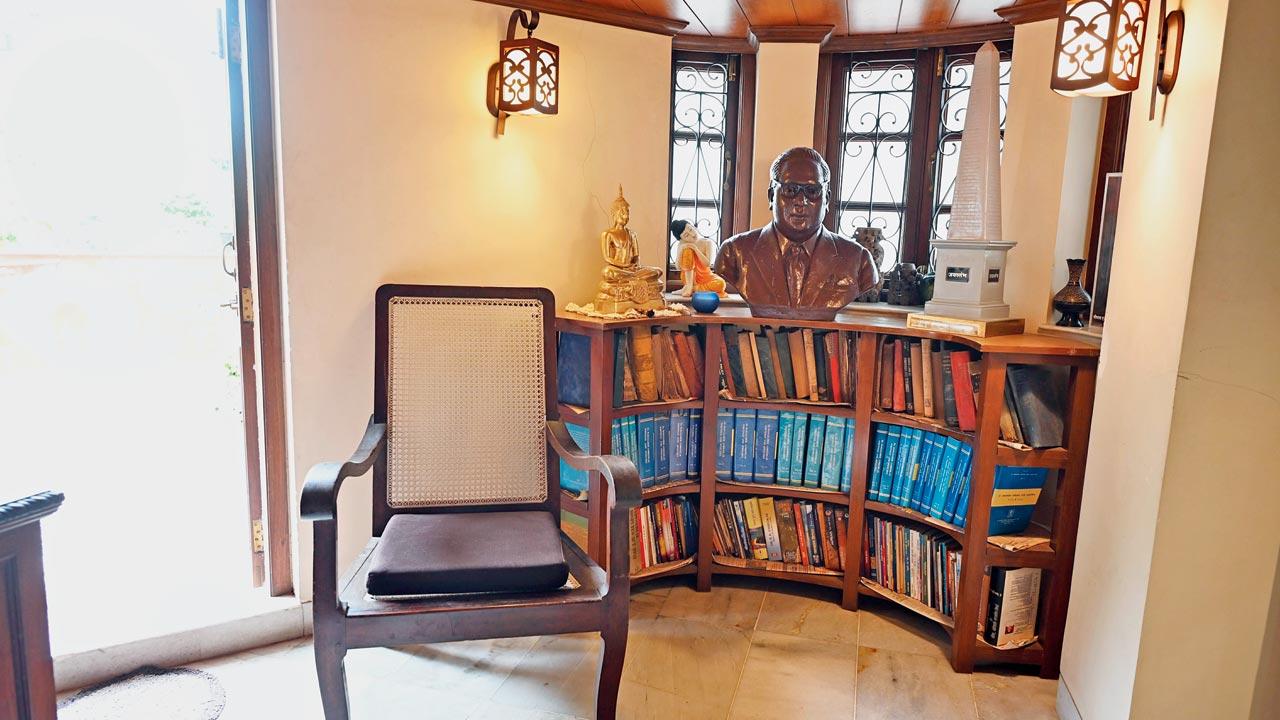

The library in Dr Ambedkar’s house. Pics/Kirti Surve Parade

The library in Dr Ambedkar’s house. Pics/Kirti Surve Parade

I found myself reading Men At Home on the cusp of Father’s Day, when images of involved, nurturing, woke work-from-home dads fill our timelines. But, as Pandey shows, the history of men at home in India — star husbands, distant fathers, traditional spouses, absent sons — is anything but simple.

Drawing on an unusual set of archives, Pandey examines the “new” man in modern India. He situates men firmly within the domestic world, revealing both their dependence and their failure to value marriage, intimacy, and conjugality, or to practice what they preached about gender, caste, and class.

Usually, men are studied through the lens of nation-building and institutional politics — that’s how old histories are framed. But Pandey’s unusual vantage point is to explore the lives of ordinary people from varied caste and class backgrounds — including many who believed in equality, wanted to change the narrative, and had the power to do so.

All these important men believed men belonged to the world, while women ruled the home — an intimate space built and nurtured through repetitive labour. They envisioned a resurgent, self-confident India, favoured education, and supported expanded opportunities for both sexes. They opposed child marriage, dowry, bigamy, widow mistreatment, and other inhumane practices, and held unorthodox views on girls’ schooling. Yet their marital histories reveal a failure to break, within family and kinship, from traditions they publicly opposed.

Despite an early failed marriage and a second idealistic union with a bal vidhwa, the famous Hindi litterateur Premchand remained deeply absorbed in his writing, often sidelining his wife. Though he shared drafts with Shivrani and read her reports in Urdu and English, he discouraged her wish to write professionally — asking why she should take on his “headache” too. In her tribute Premchand Ghar Mein, Shivrani paints a candid portrait of a reformist with fixed ideas.

A similar lack of domestic commitment marked the life of poet Harivansh Rai Bachchan, Allahabad resident and special officer in independent India’s central government, appointed by the country’s first prime minister. Despite two marriages — the second a fulfilling union with Teji Suri, an accomplished woman from an aristocratic Sikh family — Bachchan struggled to fully commit emotionally to the women in his life. He pleads helplessness and calls Teji “the man” in his life, because she managed everything. Teji, who once taught psychology in Lahore and engaged in theatre, gave up many creative pursuits to support Bachchan’s career. She handled the children and all household chores, as Bachchan admits being ignorant of domestic matters from 1941, when they married. His 1970 autobiography notes Teji bought everything — from coal and vegetables, to radios and cars.

Men at Home contextualises men’s family histories in relation to recurring features in the physical layouts of elite homes across colonial India. These layouts reflected entrenched hierarchies and gendered roles within the household. Whether in the case of Bachchan’s great-grandfather’s four-part house in Allahabad, the ancestral aristocratic haveli of Thakur Amar Singh’s princely family in Kanota, or the high-ceilinged, sprawling home of Prakash Tandon’s granduncle in the Gujarat district of Punjab, the zenana — the women’s quarters — remained out of public view. Interactions between the sexes were carefully regulated through architectural design, reinforcing the elevated status of men in family and home. Dr Ambedkar’s home, built in Bombay in the early 1930s on a 5000-square-foot plot in Dadar, also followed a certain established order: The ground floor housed rooms for his family and sister-in-law, while the upper floor was devoted entirely to his library and office, which also doubled as his bedroom — underscoring the primacy of his intellectual and political being.

I’m grateful to Men at Home — it introduced me to many men and women from Maharashtra and deepened my understanding of its gender dynamics. Four figures linked to Maharashtra stand out: Kausalya Baisantri, activist from Nagpur; economist Narendra Jadhav, who chronicled three generations of his family in Nashik and Mumbai; writer Baby Kamble, who captured life among the labouring poor in Western India; and Vasant Moon, civil servant and editor of Dr Ambedkar’s works, who lived in Nagpur before moving to Goregaon, where I was fortunate to be his neighbour.

Baby Kamble’s 1986 autobiography Jina Amucha uses the term navrepan (husbandness) to convey male privilege, power, and often unwelcome authority. Pandey observes it takes the courage and irony of an activist Dalit woman to use such a word to expose the banality of men’s assumed God-given power. The book deepened my understanding of Maharashtra and its insurrectionist language.

Reading Men at Home also gave me the privilege of engaging with Professor Gyanendra Pandey across continents. He referred to the Hindi version of the book, which he is now working on — a reimagining shaped by the language and inheritance of a different readership. He hopes the Hindi transcreation will speak to readers who are familiar with the Hindi autobiographies’ literary richness, but less so with their historical relevance. Both English and Hindi versions aim to reach a broad public, interested in domesticity and power, among them progressive scholars, radical about politics but hesitant to question family sanctity.

Sumedha Raikar-Mhatre is a culture columnist in search of the sub-text. You can reach her at sumedha.raikar@mid-day.com

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!