Four newly released books reiterate a post-pandemic reality—women’s work is underpaid and unrecognised across societies and nations

During the pandemic, the participation of women in the national workforce in India, which was among the lowest in developing countries, has plummeted to an abysmal 16.1 per cent as against the global average of 46.9 per cent. Pic/Getty Images

![]() Reading is a pleasure, but the pleasure cohabits with pain, when figures and facts draw a not-so-hopeful picture. As four new research-based publications underline new normals of the post-COVID world, the vulnerability of women across the globe is undeniable. It is evident that an infectious disease outbreak impacts all segments. But women face the harsher edge of the axe, as they are subject to an existing patriarchal social order and practices, irrespective of the health-humanitarian crises. With or without plague, HIV, Ebola, Zika or COVID, women’s lives-choices run greater risks, as reflected in the four new publications. While the books were put together after the first COVID wave, they refer to deeper structural problems and gender norms predating the pandemic. These books are guiding lights for policy makers, planners, economists or rather anyone who contributes to nation building.

Reading is a pleasure, but the pleasure cohabits with pain, when figures and facts draw a not-so-hopeful picture. As four new research-based publications underline new normals of the post-COVID world, the vulnerability of women across the globe is undeniable. It is evident that an infectious disease outbreak impacts all segments. But women face the harsher edge of the axe, as they are subject to an existing patriarchal social order and practices, irrespective of the health-humanitarian crises. With or without plague, HIV, Ebola, Zika or COVID, women’s lives-choices run greater risks, as reflected in the four new publications. While the books were put together after the first COVID wave, they refer to deeper structural problems and gender norms predating the pandemic. These books are guiding lights for policy makers, planners, economists or rather anyone who contributes to nation building.

The research on lockdown and violence against women and children is particularly eye-opening for this columnist. It is part of the book, The Girl in the Pandemic: Transnational Perspectives edited by Claudia Mitchell and Ann Smith (Berghahn Books). It collates work from eight countries across four continents, as varied as Argentina, Ethiopia, India, Poland and Thailand; researchers present vignettes from schools, hospitals, universities and streets. The book is part of the Girlhood Studies—an area of interdisciplinary research and activism—and draws on a cohesive network of girlhood scholars from North America, Europe, Russia, Oceania, and Africa, aiming at building new activist and scholarly communities.

One of the key chapters in The Girl in the Pandemic presents insights from hospital-based crisis intervention centres in Mumbai. The focus is on the increase in domestic violence and in intimate partner violence against women and girls. Three Mumbai-based researchers associated with Centre for Enquiry into Health and Allied Themes (CEHAT), a non-profit working on health, human rights and psychosocial support to violence survivors—Anupriya Singh, Sangeeta Rege, and Anagha Pradhan—state that “pandemic-related food shortages, uncertainty about the future... psychological stress from isolation and quarantine are known to increase the frequency and intensity of violence against women and children”. While admittedly reporting of violence is not the only indicator of rise in violence, but CEHAT’s findings show disturbing trends in the lockdown.

Prof Vibhuti Patel and Sangeeta Rege

Prof Vibhuti Patel and Sangeeta Rege

CEHAT presents 11 case studies from across Maharashtra, in which adolescent girls and young women suffered abuse in the family and also could not access counselling/shelter services. An 18-year-old Nitya, raped by her father for years, called the helpline after the frequency of abuse increased during the lockdown. She had tolerated the father because she was scheduled to go abroad for her higher education. But the pandemic dispelled the hopes of relocation. While she agreed with the counsellor about moving out of the house, she didn’t want police action.

The research demonstrates that violence was perpetrated by different male figures (brothers and fathers included) in the COVID crisis. In the case of Jaya, 16, home became a prison. As she longed for a connection with schoolmates and hated the piling household chores; she ran away from home even as the pandemic raged. After she was traced by the police, she admitted to the stress caused by her mother’s nagging. In other cases too, women spoke against the excesses in their parental family.

Anonymity is key to reportage of abuse and denial of access cases in The Girl in the Pandemic. Names of survivors are fictitious and time-locational indicators are deliberately blurred. For instance, young girls like Meeta, 20, faced a no-entry in Mumbai hospitals. As the hospitals treated only COVID-19 patients, Meeta’s request for an abortion was turned down. Dilaasa counsellors intervened to explain how the eight-week pregnant woman couldn’t be waitlisted as per Ministry of Health and Family Welfare guidelines. Finally, an NGO service provider was located to resolve Meeta’s medical condition.

As CEHAT’s coordinator, Sangeeta Rege, says: “Such case studies only prove how active-alert the NGO and civil society actors were at a time when the government machinery had ‘deprioritised’ women’s sexual-reproductive-mental health issues, as if COVID was the only problem to deal with.”

Dr Vibhuti Patel, the editor-contributor of Gendered Inequalities in Paid and Unpaid Work of Women in India (Springer publication) couldn’t have agreed more. “The entire nation seemed to be on hold due to the COVID-19 response. Our research showcases the immense long-term damage suffered by women in their homes and workplaces—either due to non-recognition of their home commitments or denial of wages and employee benefits in workplaces which perceive women as soft targets.” Dr Patel calls it “wage theft” as giant MNC and TNC companies failed to pay overtime; violated minimum-wage laws; and misclassified female employees as independent contractors.

Dr Patel says women were affected three times more, when compared to their male counterparts, in the COVID health crisis. Also, the participation of women in the national workforce in India, which was anyway the lowest in developing countries, plummeted to an abysmal 16.1 per cent as against the global average of 46.9 per cent. “Women were praised and deified as the frontline face of care work. But they absorbed the most negative consequences of austerity measures of the neo-liberal state... corporations treat women workforce as a precariat and an auxiliary labour that can be hired and fired as per the needs of the employers.”

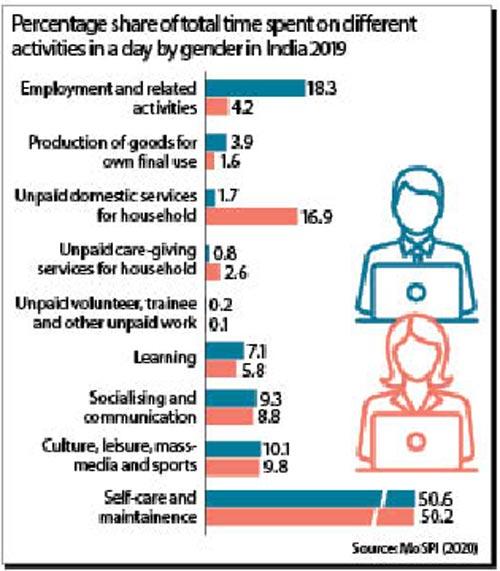

Co-editor Nandita Mondal echoes the sentiment about the “invisible” workforce of women in India. In her chapter titled, Women’s Work: Worker’s Agency and Dignity of Labour Under Lens, Mondal says unless India comes out of the “binary” of paid and unpaid work, we will be blind to the diversified, hidden and unknown work situations where women are “working”.

The pandemic, unfortunately, did not awaken us to the invisible women—dusters, cooks, sweepers, gardeners, tutors, courier receivers, embroiderers, knitters, storytellers—in our homes/ lives. Dr Patel, in another book titled Women and Work in Asia and the Pacific: Experiences, Challenges and Ways Forward (Massey University Press), concludes in no uncertain words: Total employment in India for November 2020 was 2.4 per cent lower than in November 2019, but among urban women it was down by 22.8 per cent. Of the 6.7 million women displaced from the labour force during this period, 2.3 million were rural women, while 4.4 million were urban women. Urban women faced the deepest losses with a labour force contraction of 27.2 per cent.

A policy brief released by the United Nations, The Impact of COVID-19 on Women, observes categorically that the pandemic will likely reverse many of the limited gains made in achieving gender equality in the past decades (UN Women, 2020). The book, Women and Work in Asia and the Pacific, addresses this reality in different scenarios. It’s a long overdue assessment of working women’s challenges and opportunities during the COVID-19 pandemic in 10 countries in Asia Pacific— Aotearoa New Zealand, Australia, Japan, China, Cambodia, India, Sri Lanka, Fiji, Pakistan and the Philippines. These countries symbolise Asia Pacific’s diversity in terms of scale, development stage, economics, religion, politics and history. Despite the differences, they are unfortunately comparable in one aspect: discriminatory regulations-practices, and unfair behaviours, attitudes towards women.

Many researchers point at “a rapid masculinisation” of the Indian workforce under pandemic conditions, at all levels and in all sectors of the economy. It is found that industries are pushing women out of careers like team managers, entrepreneurs, beauticians, fitness trainers, tourist guides and restaurant owners. As per a study on the unorganised sector—only eight per cent of women workers/employees in India have permanent jobs and protection of labour legislation—women were worse off after the announcement of lockdown, because their work (even in normal circumstances) lacks dignity of labour, social security, decent and timely wages, and, in some cases, even the right to be called a “worker”. Migrant women workers who are at the bottom of the informal employment pyramid, work as part-time, contract, unregistered, and

home-based workers.

Patel elaborates on a similar point about migrant female workers in a chapter in the new volume, Reimagining Prosperity: Social and Economic Development in Post-COVID India (Palgrave Macmillan). She says women pushed into poverty due to the pandemic outnumber men, especially since a larger number of small and nano women’s enterprises shut down. These female daily wage labourers, head-loaders, construction workers, street vendors, domestic workers, small-scale manufacturing wor-kers in recycling, scrap and garment industries, remain undocumented due to the absence of gender-segregated data.

In an ideal world, the COVID-triggered crisis could have been a good start for additional state support to women. This was also a wake-up call to initiate gender-responsive budgeting to reduce women’s burden of poverty; and remove systemic discrimination in education, skill training, healthcare and employment. But ours is a different world in which women have to move mountains for minor mercies like seeking entry to a public shrine or gaining access to potable water.

Sumedha Raikar-Mhatre is a culture columnist in search of the sub-text. You can reach her at sumedha.raikar@mid-day.com

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!