Scholar Prachi Deshpande positions the ancient cursive script as an unusual but enriching vantage point to understand Maharashtra’s history and regional identity

Prachi Deshpande’s new book examines how the usage of scripts like Modi, fallen out of everyday use, can tell us a lively history of language practice

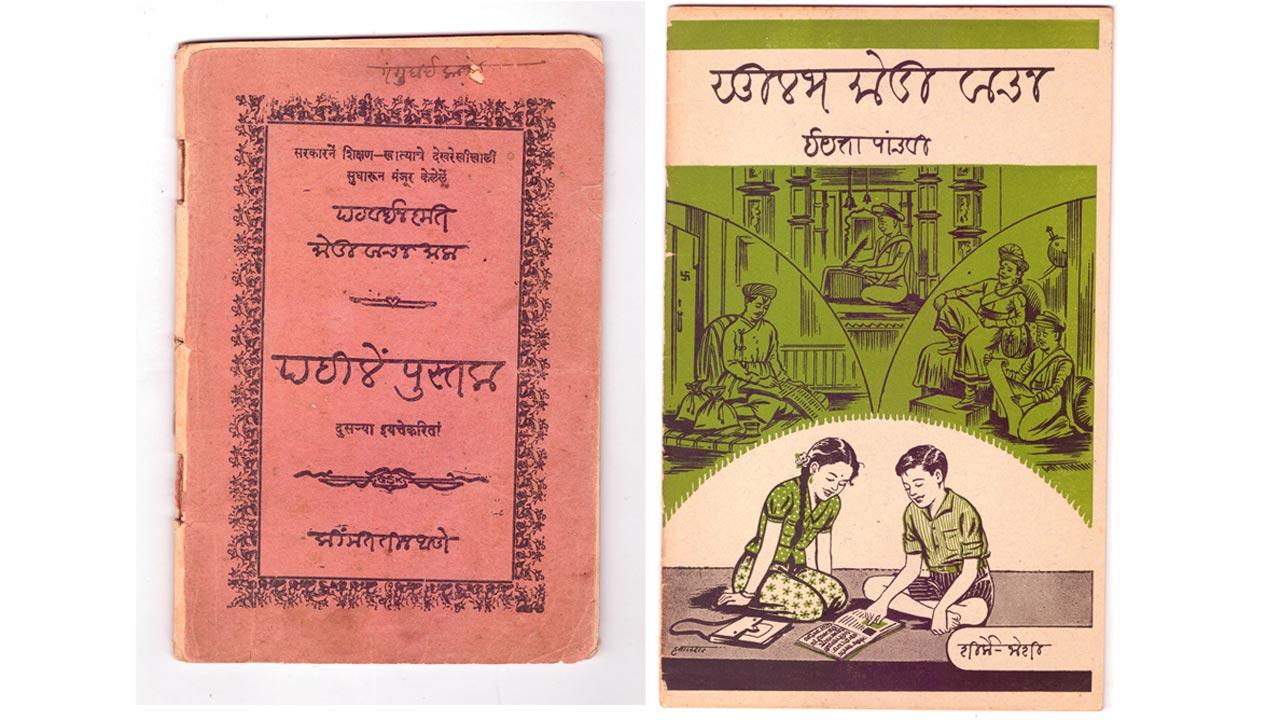

![]() Thirteenth-century polymath-scholar Hemadpant is said to have given birth to the Modi script. Medieval scribes believed that he received the lipi as a gift from the king of Lanka, Vibhishana, for saving the former from a difficult ailment. However, Modi, as per some scholars, goes close to the cursive Mudiya in Rajasthani, as well as the Mahajani in Gujarati writing. The Modi script, key to Marathi record-keeping for centuries, was modelled on the broken-bent-cursive form out of the Perso-Arabic writing system prevalent in South Asia.

Thirteenth-century polymath-scholar Hemadpant is said to have given birth to the Modi script. Medieval scribes believed that he received the lipi as a gift from the king of Lanka, Vibhishana, for saving the former from a difficult ailment. However, Modi, as per some scholars, goes close to the cursive Mudiya in Rajasthani, as well as the Mahajani in Gujarati writing. The Modi script, key to Marathi record-keeping for centuries, was modelled on the broken-bent-cursive form out of the Perso-Arabic writing system prevalent in South Asia.

Academic-scholar-author Prachi Deshpande’s new book Scripts of Power follows the trajectory of the Modi lipi. More than its legendary origins—folklore and trivia served as finger food to the main course—she is interested in how and where people used the script, and their attitudes to it. Deshpande, associate professor of history at the Centre for Studies in Social Sciences, Kolkata, calls Modi “an opaque text” which is present as well as absent in the larger story of Maharashtra’s history. So many Modi records are available in archives and in print, but the script itself is no longer in regular use. She urges the reader—not necessarily a Maharashtrian, but anyone curious about the history of change—to see the different ways in which a visually symbolic script can alert us to historical processes.

Deshpande maps key documents (in Modi and Balbodh), and also how different shorthand scripts came into regular usage in offices and police surveillance

Deshpande maps key documents (in Modi and Balbodh), and also how different shorthand scripts came into regular usage in offices and police surveillance

In contemporary Maharashtra, such a big deal is made of the glorious Maratha past; an even bigger political deal is made of the usage of Marathi in the power corridors. Admittedly, the political leadership of a linguistically-formed state should lobby for its “own” language. But a fresh look at how Modi and other scripts have been used and talked about over time—in essence a cultural history of scripts—can make us aware and sensitive to a more layered history of that language and its interactions with other languages?

Like every year, February 27 will be celebrated with aplomb as the Marathi language day in Maharashtra. Deshpande, in one sense, pulls us much behind current time to show how the claims for the linguistic state were preceded by decades of debate about an appropriate script, orthography, and standard language. These debates and reforms were crucial to claims made about the viability and efficiency of Marathi as a language of administration. Similar claims were made in many linguistic state movements in India, which the book puts in perspective for the reader.

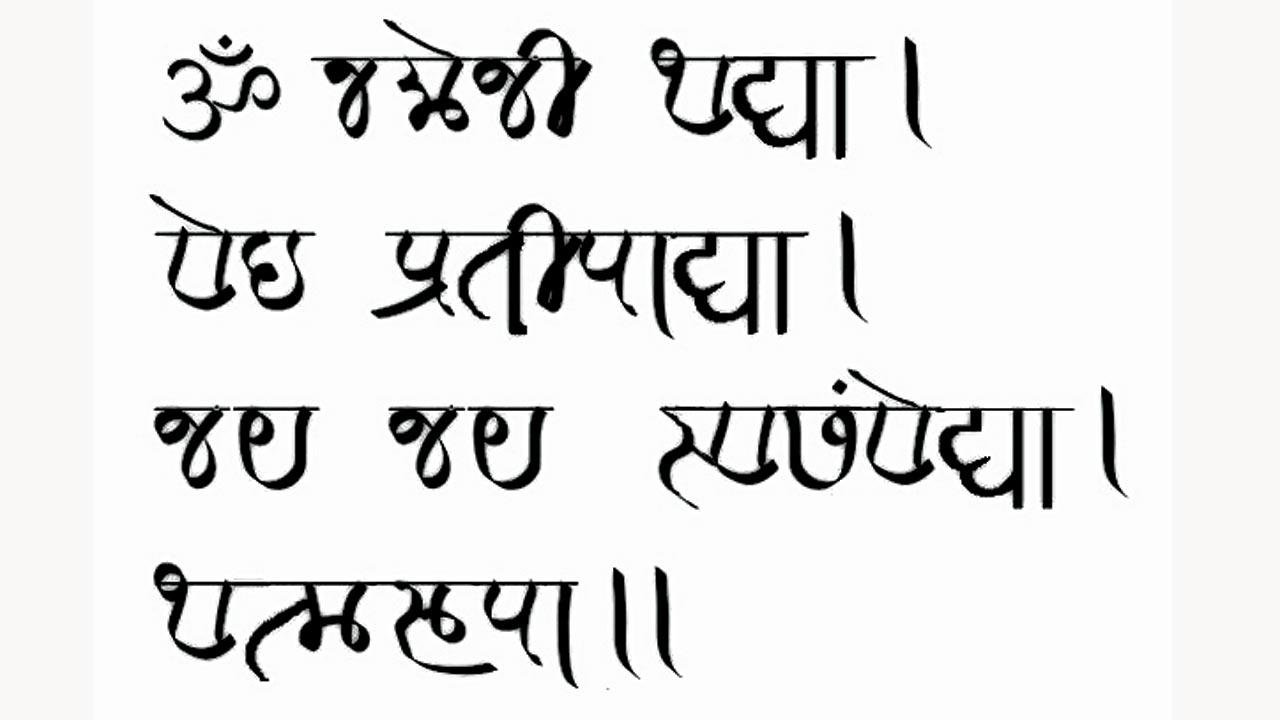

A verse of Dnyaneshwari in Modi script. Pic/Wikicommons

A verse of Dnyaneshwari in Modi script. Pic/Wikicommons

“A study like this one on how a script like Modi was used and debated, allows us to see the linguistic and cultural cohesion ‘produced’ over time from previously multilingual spaces, in order to make our postcolonial linguistic states possible. So Modi’s trajectory is a starting point—a framework to investigate the political models we inhabit,” says Deshpande, 51, who lives in Kolkata, but travels across the length and breadth of India as a speaker on niche research areas like language histories, cultures of documentation, multi-linguality, historiography and memory. She is also the recipient of the Infosys Prize 2020 in Humanities for her nuanced and sophisticated treatment of South Asian historiography.

Her first book, Creative Pasts, dwells on the Maratha period as a defining era in the history of Western India. She shows the links between historical and literary narratives, which impacted history-writing practices and the making of “a modern Marathi regional consciousness”. Deshpande’s sound fact-based presentation, marked by academic rigour, is valuable in today’s emotionally-charged times when Maharashtra, the second-most populous Indian state, has been a perpetual hotbed of identity politics.

Deshpande is from a multilingual family herself. She was born in Pune and raised in Panchgani. Her family is from Bagalkot in north Karnataka. She was raised speaking both Kannada and Marathi at home. She was educated in Pune, New Delhi and the United States, where she taught for many years before returning to India. Living and teaching in Kolkata for over a decade has enabled her to become a fluent Bengali speaker. In many ways, she says, her study of language and script usage is an effort to give the deep-rooted Indian multi-linguality, “which is more common than rare”, a concrete history.

Deshpande’s book on Modi lipi opens many windows. “I was intrigued by the fact that although there is such a huge bureaucratic archive in Marathi in Modi script spanning over eight centuries, the body of writing has never really figured in any discussion of Marathi language history.”

Deshpande’s book breaks the notion of language history as only the history of literature. She shows how the usage of different scripts, even those like Modi which have fallen out of everyday use, can tell us a lively history of language practice, which in turn speaks about social relations and power.

Modi, at one point, was seen as not “complete enough” for print because it didn’t have separate signs for all vowels. Similarly, it had abbreviations of frequently appearing words, which quickened the writing for the scribe, but reduced the readability for the general public. After the advent of typewriters (1950s), Modi lost its currency. But Deshpande argues that Modi’s calligraphic characteristics cannot be the reason to overlook its archival worth. She advises scholars to relook at an everyday history of the Marathi language through the lens of the cursive script, whose earliest available samples date back to the time when the Deccan sultanates incorporated local languages in record-keeping alongside Persian.

Also read: The surgical neck

Scripts of Power awakens the reader to the pace of change in the state. She maps the key documents (in Modi and Balbodh), which were produced by scribes, and also how different shorthand scripts came into regular usage in offices and police surveillance. She shows how this world of writing changed when the Maratha karkun became the clerk in the British colonial office, and Devanagari eventually became the official script.

Scripts of Power is an exhaustive read in all senses of the term—its bibliography runs into 40 pages. The book references texts as varied as A Grammar of the Mahratta Language to Which Are Added Dialogues on Familiar Subjects (1805) and University of Bombay Examination Papers dating back to the 1920s. There are times when it provides Modi documentation in micro-details, some of which speaks only to academic peers. For instance, the chapter on Scribal Worlds: Writerly Selves outlines the paper, stylus and ink used by the lekhak/karkun in the daftar space. In yet another instance, the author delves into the infinite assemblage of speech, script, norms and practices that the Pishacchalipika (Modi was given that demonic epithet) manual articulated. In fact the manual admits that erudition of an unimaginable level is required in the scribe to decode nana deshi nana riti nana lekhan nana yukti (different practices of different lands).

If there is one point that Scripts of Power underlines to the hilt, it is the coexistence of Modi lipi with other writing systems across the Maratha imperial domains. Marathi, in the Modi script, was in currency in Kannada-speaking areas of the Krishna-Tungabhadra doab, in the 16th century. In fact Kannada writings of the period were full of Marathi and Persian revenue terms. Deshpande states that, whatever nationalists and language puritans thought, India is blessed with a rich, contradictory and polyglot history of language practice. It defies the monolingualism imposed by formal state boundaries and archival structures. It is here—in the healthy space of cultural give and take mapped by the historian—that we Indians, including Maharashtrians, should see the future of our languages.

Sumedha Raikar-Mhatre is a culture columnist in search of the sub-text. You can reach her at sumedha.raikar@mid-day.com

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!