Is the selfie making high jewellery more coveted than designer clothes? Sabyasachi Mukherjee taps into the generational shift in jewellery’s traditional clientele

A tribute to the late actor, Leela Naidu, the Naidu Choker is an assortment of 92 carats of pigeon blood Burmese rubies, assembled with rose cut and brilliant cut diamonds. Pics Courtesy/Sabyasachi/Naina.Co

There’s a reason why Sabyasachi Mukherjee is known as the sort of disruptor who can set the tone for what a designer can and cannot do.

There’s a reason why Sabyasachi Mukherjee is known as the sort of disruptor who can set the tone for what a designer can and cannot do.

ADVERTISEMENT

He repackaged cultural nostalgia as the next big idea and celebrated Indian-ness to rise to success. The list of Sabyasachi x… high-profile collaborations include Christian Louboutin, Bergdorf Goodman, Pottery Barn and H&M. He changed the way brides, grooms and their families too, dressed on their big day with unabashed vitality. Instead of primetime slots at fashion weeks, he engaged in a direct dialogue with his 5.6 million Instagram followers to showcase high jewellery and wedding ensembles.

This deconstructed Jadau titled, the Maharani Necklace, inspires a sort of bohemian-royal personality wearing a languid assortment of uncut diamonds, sapphires, tourmalines and pearls

This deconstructed Jadau titled, the Maharani Necklace, inspires a sort of bohemian-royal personality wearing a languid assortment of uncut diamonds, sapphires, tourmalines and pearls

Now, the 49-year-old has his ambitions set on consolidating his brand’s position in India’s $60 billion jewellery market. Launched in 2017, Mukherjee expects the revenue from his jewellery line to reach Rs 150 crore in FY24. “The idea is to build a three-billion-dollar Sabyasachi Calcutta business by 2030. I am very systematic with planning, and I have immense patience,” says the designer, who sells India’s first branded mangalsutra (approx R1.5-2 lakh) as part of his fine jewellery line, with mang tikas, alligator and tiger cuffs and pendants.

For once, no one was looking at clothes. At an intimate salon-style high jewellery presentation in New Delhi recently, Mukherjee indulged the jewellery equivalent of sensory overload to unpack a story of “modern royalty” through precious gemstone-centric creations. To wit: The Minerva necklace featured an assembly of emeralds, rubies, tourmalines, morganites, surrounded in 18k gold and VVS-VS diamonds. He called it: “Sunday thrifting at Sudder Street, Calcutta...”

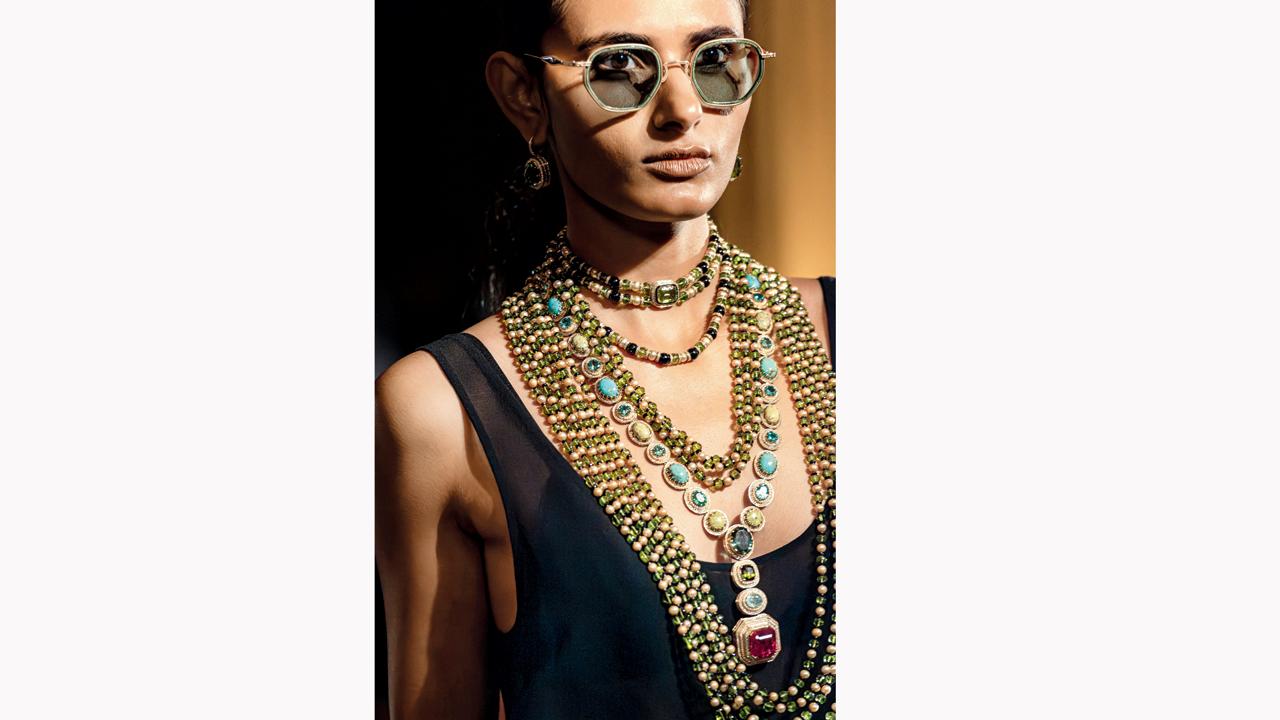

The Eden Suite is a collection of emeralds, tourmalines, peridots, opals, pearls and turquoises highlighted by a 41 carat rubellite, set in 18k gold with VVS-VS diamonds

The Eden Suite is a collection of emeralds, tourmalines, peridots, opals, pearls and turquoises highlighted by a 41 carat rubellite, set in 18k gold with VVS-VS diamonds

An abstract expressionist approach to the 24-piece collection foraged through the gamut of colours, gem families, origins and influences; each piece telling a story of bold, proportioned design and time-and-labour intensive craftsmanship and had that hey-look-at-me chutzpah that all but screamed modern heirlooms. Mukherjee, to his advantage, understands that high-design jewellery is at least as much about vanity as it is about art.

“I create businesses by trying to understand where the society is moving,” says Mukherjee in a phone interview. Specifically, he is interested in exploring the schism between high and fashion jewellery. “We are playful with stones; the styles are hyper-versatile and democratic. They are more personality driven, and not designed to match your clothes but to find its own point of view.”

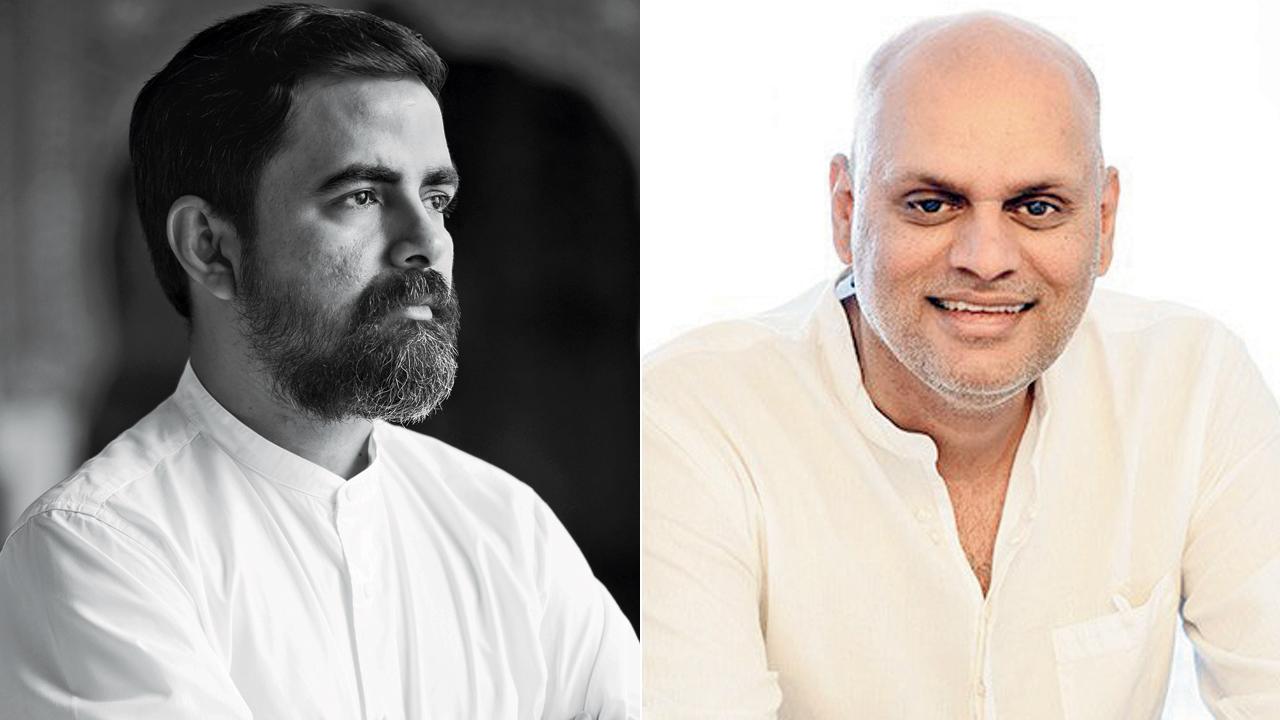

Our jewellery is disruptive in the sense that we combine the best of craftsmanship, aesthetic exuberance and rare gemstones for customers to invest in—with clean money, which is exactly the opposite of what has been happening in the jewellery industry, Sabyasachi Mukherjee; (right) When lab-grown diamonds started to lose their lustre, the desire for Polki jewellery exploded with Bollywood weddings. Jewellers in Jaipur, Bikaner and Hyderabad quickly caught up. Social media’s equalising force provided visibility to the gemstones, and it didn’t matter if most couldn’t afford them. Period dramas like Jodha Akbar and Padmaavat further fueled aspiration towards coloured stones, Pramod Kumar KG, co-founder of Eka Cultural Resources and Research

Our jewellery is disruptive in the sense that we combine the best of craftsmanship, aesthetic exuberance and rare gemstones for customers to invest in—with clean money, which is exactly the opposite of what has been happening in the jewellery industry, Sabyasachi Mukherjee; (right) When lab-grown diamonds started to lose their lustre, the desire for Polki jewellery exploded with Bollywood weddings. Jewellers in Jaipur, Bikaner and Hyderabad quickly caught up. Social media’s equalising force provided visibility to the gemstones, and it didn’t matter if most couldn’t afford them. Period dramas like Jodha Akbar and Padmaavat further fueled aspiration towards coloured stones, Pramod Kumar KG, co-founder of Eka Cultural Resources and Research

The history of gemstone trading and jewellery making in India goes back more than five millennia. Golconda diamonds from Hyderabad, sapphires from Kashmir, and pearls from the Gulf of Mannar were coveted. Jewellery embedded with precious stones was not only for the pleasure of adornment and sealed the social status of the wearer but also spoke of myths and legends. In the Mahabharata, Amrita (the immortality potion) consisted of water, herbal juice, liquid gold and dissolved gemstones. The 5th century Hindu text, the Ratnapariksha chronicles the symbolism of each birthstone to deities, planets, and days of the week. “The coloured stones are an intrinsic part of the Indian psyche. Their talismanic properties also played a role in some form or other,” says Pramod Kumar KG, co-founder of Eka Cultural Resources and Research, specialising in design archives, exhibitions and museums. Kumar recalls how two decades ago, when the owners of international jewellery houses known for their elegant diamond styles visited India, their wives went home purchasing coloured gemstones. “We are a country of colour,” he adds.

Sometime in the 1980s and 1990s, the demand for large, statement gemstones moved out to let the lighter, conservative designs take centre stage. Solitaires became the sparkling markers of significant celebrations and wealth, and self-gifting diamonds served as a symbol of achievement and empowerment for women. “In the past, a lot of people didn’t buy jewellery as an investment but to store unaccounted wealth, boosting the business of lab-grown solitaires. As it required minimal design and making charges, it was an easier option if you wanted to liquidate and get almost all the money back. This greed to store wealth obliterated the [coloured stones] market, taking away the role of a paramparik karigar; it is their expertise that brings real value to jewellery,” believes Mukherjee. “The secret to truly enjoying my jewellery is to turn it over. The back of the jewellery is intricately crafted with Bengal filigree work—a craft heritage—and studded with diamonds.”

In an industry where pricing traditionally has been dictated by the cost of precious materials, Mukherjee holds the heritage of craftsmanship more valuable. “What would become more rarefied than the rarest of stones is craftsmanship,” he asserts. According to a Bloomberg report in November 2023, LVMH forecasts a deficit of 22,000 workers by the end of 2025.

There’s also the changing face of the jewellery-buying customer. “In a selfie, the focus is on makeup and jewellery, not the clothes,” he quips. The new confident, fashion-conscious generation—which Mukherjee calls a “generation of startups”—is not shackled by the myth of jewellery as the once-in-a-lifetime investment to be stored in a bank locker. “I want to create jewellery that fulfills both, desire for wearability and investment. Jewellery like real estate appreciates no matter how many times you wear or inhabit it.”

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!