Inspired by the late Urdu scholar-poet Naiyer Masud’s stories, a film school graduate sets out to capture the historic city of Lucknow in his debut docu-fiction

Shahi AJ (right), assistant director Naazir Khan, seen with Naiyer Masud’s youngest brother Azad (centre) at the family’s ancestral residence in Lucknow

![]() The are some moments of stillness, silence and pitch darkness in Shahi AJ’s film, Letters Unwritten To Naiyer Masud. It’s as if Shahi is trying to make sense of the difference between the modern-day crammed, chaotic Lucknow in front of his eyes, as against the aristocratic Adabistan he read about in Masud’s stories. Shahi’s appreciation of the urban change reflects in blackouts on the screen. What happened to the epitome of etiquette? How did Masudsaab perceive the decline at the end of his life? Questions mount and make their way on to the screen.

The are some moments of stillness, silence and pitch darkness in Shahi AJ’s film, Letters Unwritten To Naiyer Masud. It’s as if Shahi is trying to make sense of the difference between the modern-day crammed, chaotic Lucknow in front of his eyes, as against the aristocratic Adabistan he read about in Masud’s stories. Shahi’s appreciation of the urban change reflects in blackouts on the screen. What happened to the epitome of etiquette? How did Masudsaab perceive the decline at the end of his life? Questions mount and make their way on to the screen.

Shahi AJ’s hour-long docu-fiction merges animation sequences with documentary footage. It unfolds as a series of visual letters written to a literary figure by members of his fan club who—while making a film on the writer’s worldview—are looking for quaint Lucknow locales and mansions evoked in Masud’s writings.

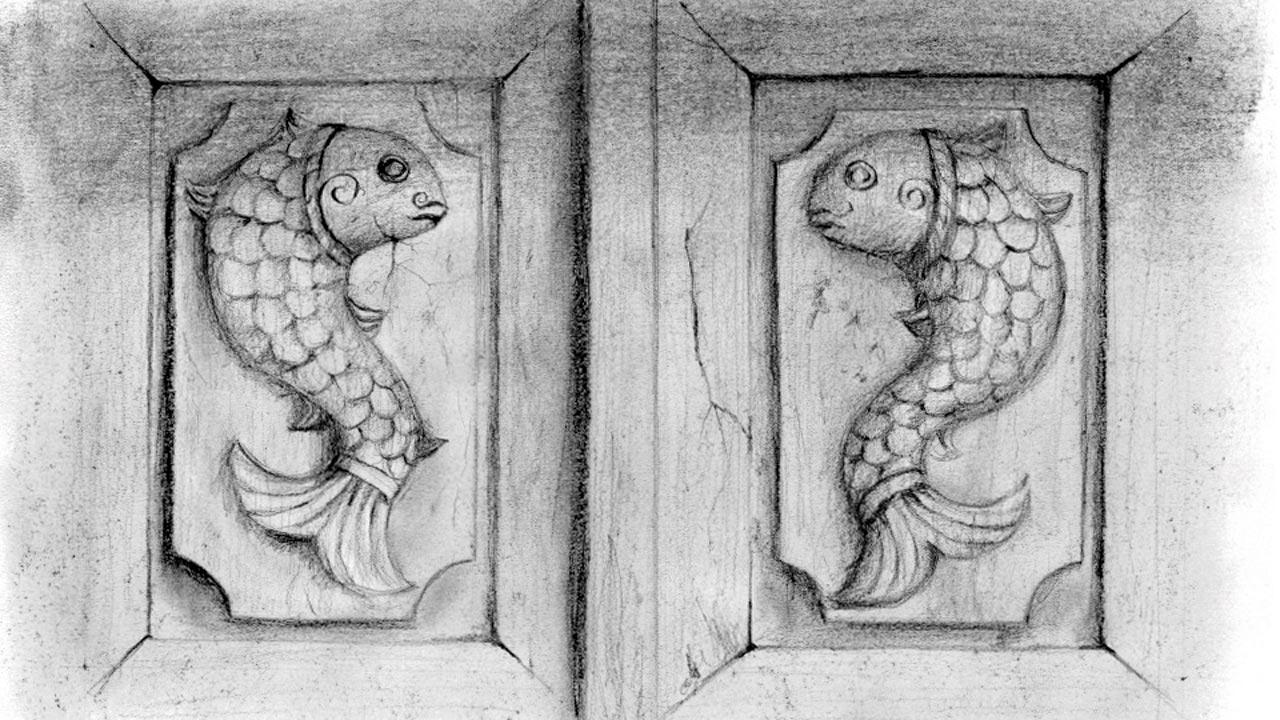

Shahi AJ’s film follows Lucknow’s broken arches, pulpits, old verandahs and facades with fish insignia that came alive in Naiyer Masud’s stories

Shahi AJ’s film follows Lucknow’s broken arches, pulpits, old verandahs and facades with fish insignia that came alive in Naiyer Masud’s stories

The film crew is alive to the curios scattered around the city, Lakhori bricks peeping out of foreign plaster, dilapidated but ornate structures born out of the desires of nawabs, and most importantly, the twin fish insignia found in artefacts and facades. As the film crew navigates through the chaotic and polluted Lucknow, they talk to the litterateur’s friends, fellow Lucknow residents, who provide further clues to the magical world in Masud’s stories. Friends and fans piece together a hidden obscure universe.

Also Read: Oxus between Harappans and Aryans

This is Shahi’s debut feature—it just screened at the 2023 International Film Festival Rotterdam—after graduating from the Film And Television Institute in Pune in 2018. But much before he set out to do a recce for his project in Lucknow, he became an ardent fan of the Urdu writer, who also taught Persian at the Lucknow University. Shahi was influenced by the translated English stories. “It was like an instant bond with a bygone soul. As I read the Essence of Camphor, Weathervane, The Colour of Nothingness, Interregnum and The Occult, I sensed the universal truths in each story. Though geographically set in yesteryear decadent spaces,

they spoke to me and my batchmates,” says Shahi. Masud reminded him of great writers like OV Vijayan and Vaikom Muhammad Basheer who retained their regional ethos, and underlined contemporary realities.

Shahi, who grew up in Kollam, Kerala, and currently teaches at St Joseph Communication College in Changanassery, needed a translator to appreciate Masud’s nuanced world of Lucknowi tehzeeb. He found one in fellow student Naazir Khan who doubled up as the film’s assistant director; Ashwin Ameri, another FTII fellow, took on cinematography. The trio did a recce in 2018, before the project received grant support from the India Foundation For The Arts. The film demanded four extensive Lucknow trips, since interviews of Masud’s friends (senior citizens) were essentially reflective. A shooting schedule in a pandemic-impacted Lucknow was a risk in itself, considering the high death rates, lockdown protocols and a delicate law and order situation.

Also Read: The moon’s a balloon

Interestingly, Shahi weaves in the low-budget filmmaker’s anxiety into the film fabric. While Masud’s fans are writing letters to the litterateur about the decaying cityscape, Shahi’s Amma makes tense phone calls about the raging Coronavirus and scary breaking news. Viewers are privy to that conversation too. The film assumes an epistolary form in which actual letters (text) become visuals, and voiceovers become vehicles of angst. The narrative is not driven by one single voice—different fans are trying to reach a departed mystical figure; two letters are addressed to an “Ibru” who couldn’t join the unit in Lucknow.

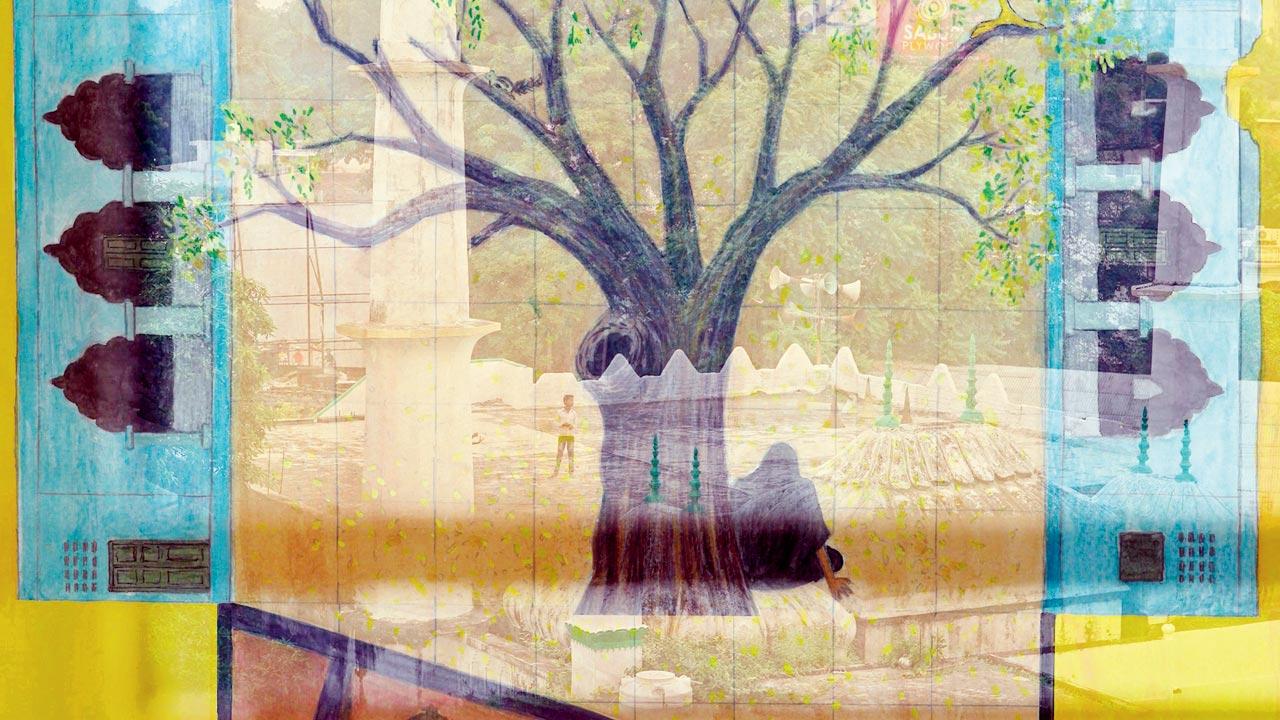

Bharath Murthy imagines Urdu writer Naiyer Masud’s abode Adabistan. The old style aristocratic mansion is a metaphor for Lucknow

Bharath Murthy imagines Urdu writer Naiyer Masud’s abode Adabistan. The old style aristocratic mansion is a metaphor for Lucknow

The film is a collective exploration of a real versus fictional world, at the heart of which stands the imagined Adabistan, the abode of Naiyer Masud. One of the members of the fan club, Bharath Murthy, maps Adabistan in charcoal animation drawings, which come alive when Azad Masud—the writer’s youngest brother—throws open the ancestral residence; similarly, Timsal Masud, his son and academic, opens another window when the family album locates the writer’s younger self amid siblings. The most interesting voice is that of the caretaker of Murd Maidan, the cemetery where Masud is laid to rest, who does Chikan embroidery in his spare time. He seems like a strange, but likeable figure who “has written a sequel to Umrao Jaan”.

Interestingly, Naiyer Masud never spelled out the Lucknow backdrop in his stories in plain simple terms. His subtle mentions were more of mood setters—the miniature palace made of tiny stone bricks placed in the reception room; the palanquin sitting atop an octagonal table; layers of curtains fashioned out of fine colourful fabric. Shahi says the atmospherics transport the reader to a peculiar milieu and architecture. Similarly, in Interregnum, Masud paints a large room with long wooden shelves of neatly arranged books. Shahi says Masud’s constructions and settings were so unique and provoking—“Amid the scent of old papers, he appeared no more than an old dog-eared book himself!”

In an earlier interview Naiyer Masud was questioned about why he didn’t explicitly pin down the time and place specificity, though the glimpses of a decadent Lucknow are evident. Masud said his wondrous birthplace is in his consciousness. The city’s arches exert a hypnotic pull over him. “Formerly there were quite a few arches in Lucknow, standing hushed in a landscape of decay. Today, only a few of them remain. If you have the time, come along with me.” Masud was intrigued by a lone arch with broken brick walls stretching for several furlongs in all directions. He said “whenever I see an arch, a verandah, a passageway... those in the background as well as those which I was able to see before they were swept away... they begin to crowd before me.”

Shahi’s film also follows the same broken arches, pulpits, verandahs which today stand amid dish antennas, clickety rickshaws-tempos, and billboard ads of vests and paan masala. The street is in fact one of the main characters in Letters Unwritten To Naiyer Masud. The filmmaker senses the pulse of the city by capturing the people on the streets—those bathing under a roadside tap, hand-cart vegetable vendors, pavement hawkers, chikankari store owners. As Samir Kher, Lucknow chronicler-storyteller puts it: The current state of Lucknow cannot be assessed only in its glorious past. But the present too, in every way, is a part of Lucknow. “There are people who look at Lakhori bricks and appreciate it. There are others who will just see a plot to build a mall, and it is fair.” Kher plays a guide in the film; he advises the Lucknow explorers to lose themselves in the city’s nooks and crannies.

Finding the old dilapidated, discarded ruined part of Lucknow is an educational journey. It opens the viewers’ eyes to the gems hiding in plain sight, possibly more apparent to the outsider than the insider.

Sumedha Raikar-Mhatre is a culture columnist in search of the sub-text. You can reach her at sumedha.raikar@mid-day.com

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!