Celebrating some rare exhibits in the special collections of the Asiatic Society of Mumbai, which completes 220 years this week

The iconic facade of the Town Hall, which houses the Asiatic Society of Mumbai. File pic

The most magnificent structure that taste and munificence combined have as yet erected in India.” So declared Sir John Malcolm, Governor of Bombay, in 1930, describing the Neoclassical architectural marvel that is the Town Hall at Horniman Circle, which houses the State Central Library and the Asiatic Society of Mumbai (ASM). The landmark marble edifice, designed by Colonel Thomas Cowper of the Bombay Engineers, makes an imposing sight, with its dramatic flight of 30 massively expansive steps ascending to meet a pedimented portico with eight iconic Doric columns. Inside, a beautiful wrought iron staircase rises to the vestibule.

The most magnificent structure that taste and munificence combined have as yet erected in India.” So declared Sir John Malcolm, Governor of Bombay, in 1930, describing the Neoclassical architectural marvel that is the Town Hall at Horniman Circle, which houses the State Central Library and the Asiatic Society of Mumbai (ASM). The landmark marble edifice, designed by Colonel Thomas Cowper of the Bombay Engineers, makes an imposing sight, with its dramatic flight of 30 massively expansive steps ascending to meet a pedimented portico with eight iconic Doric columns. Inside, a beautiful wrought iron staircase rises to the vestibule.

Originally known as the Literary Society of Bombay, the Asiatic Society of Bombay was founded by Sir James Mackintosh, a distinguished lawyer who became the Recorder or the King’s Judge for Bombay. When it first met on November 26, 1804, with the intention of “promoting useful knowledge, particularly such as is immediately connected with India”, the formally quoted objective was investigation and encouragement of the Oriental Arts, Sciences and Literature. The Literary Society purchased the collections of the private Medical and Literary Library, which formed the nucleus of the vast present library boasting well over three lakh books and bound volumes.

After the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland was introduced in London in 1823, the Literary Society of Bombay became affiliated and known as the Bombay Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society from 1830, the year it moved into the Town Hall building. The Bombay Geographical Society merged with it in 1873, followed by the Anthropological Society of Bombay in 1896. In 1954, it separated from the Royal Asiatic Society and was renamed the Asiatic Society of Bombay, before acquiring its present name in 2002.

This short administrative history sets the scene for discussing some rare holdings within the hallowed walls. In consultation with the quietly dynamic ASM President Vispi Balaporia, Vice President Shehernaz Nalwalla and Honorary Secretary Mangala Sirdeshpande, we shine the light on a fistful of treasures with interesting stories of origin.

Stunning in stone

The Sopara relics: five caskets from the stupa and a bronze image of Maitreya, the Future Buddha. Pics Courtesy Asiatic Society Of Mumbai/Anurag Ahire

The Sopara relics: five caskets from the stupa and a bronze image of Maitreya, the Future Buddha. Pics Courtesy Asiatic Society Of Mumbai/Anurag Ahire

Ranking high among the Society’s prized antiquities are eighth to ninth-century relics excavated in 1882 at Nala Sopara, north of Bombay, by Pandit Bhagvanlal Indraji, archaeologist, numismatist, epigraphist and Honorary Fellow of the Society. Having received notes on these remains from the Bombay Gazetteer compiler James Campbell, Pandit Bhagvanlal visited the spot with Campbell. They were able to dig, in situ, a large stone coffer of a stupa.

“When nothing was previously known or written on the subject, it was Pandit Bhagvanlal who identified the site of Sopara with ancient Surparaka or Soparaka mentioned in Buddhist, Brahmanical and Jaina texts, and in the inscriptions of Western Indian caves,” writes Devangana Desai in the essay “Sopara—Pandit Bhagvanlal Indraji and After”.

The stupa centre contained eight significant bronzes—the Seven Buddhas and Maitreya the Future Buddha—seated around a copper casket, which in turn encased four more caskets. Placed one within the other, these were of silver, jade, crystal and, finally, gold. Evidenced from relevant Buddhist texts, Pandit Bhagvanlal suggested the 13 tiny fragmented earthenware pieces in the gold casket, with gold flowers, were relics of Gautama Buddha’s begging bowl.

His novel finds fanned an expected stir in India, Sri Lanka and Europe. The Bombay Government presented the Sopara relics to the Society, which displays the coffer in the vestibule, while the relics are retained in safe custody.

‘She sells more than she buys from us’

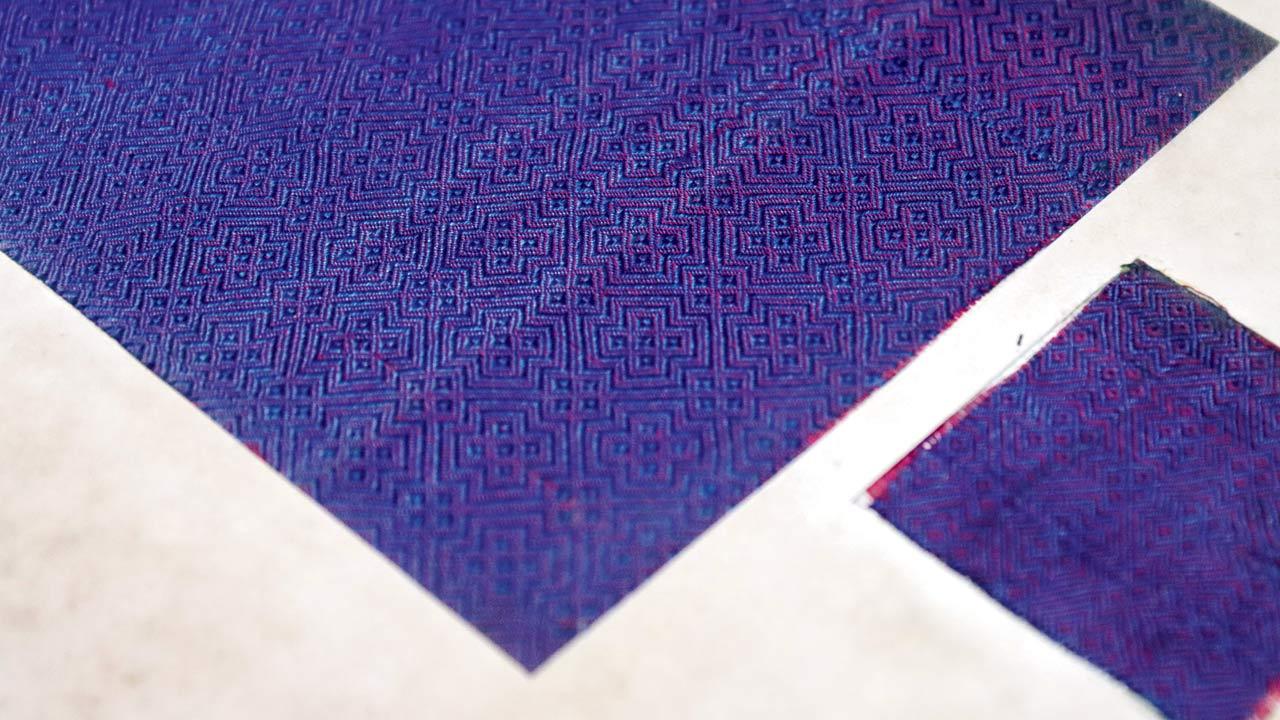

Thana silk swatches from Watson’s volumes documenting Indian textiles

Thana silk swatches from Watson’s volumes documenting Indian textiles

This telling line opening John Forbes Watson’s in-depth publication, The Textile Manufactures of India, summarises the economically expedient plan the Raj masterminded to cripple the production of hand-woven Indian cloth. The 18-volume compendium over two editions, in 1866 and mid-1870s, was published by the India Office, which became the India Museum when the Crown took over.

Watson was a surgeon by training, briefly working at Bombay’s Grant Medical College till he returned to London. Officially designated Director of the India Museum and Reporter on the Products of India for the Secretary of State, he was strategically assigned this meticulous chronicling. The project findings circulated among Lancashire and Manchester mill owners who copied these textiles on their machines. Using about 700 samples available at the India Office, Watson categorised the detailed entries of the set by utility, fabric and ornamentation.

“Twenty sets of 18 volumes each were produced, 17 distributed in England and three to India,” explains textile researcher and curator Savitha Suri. “The India Office served as a huge repository of information on the subcontinent, documenting whatever could be replicated with ease. As the Town Hall at Urbs Prima in Indus, the ASM may have been one of the beneficiaries of the ‘largesse’.”

With textile factories mushrooming after Cowasji Nanabhai Davar started the Bombay Spinning Mill in 1854, the set enabled more mill owners here to readily avail of its contents.

“Bombay’s fine history of hand block printing fused traditional and contemporary design languages,” says Suri. “The East Indians had their ‘lugra’, whose documentation has gained traction after centuries of neglect. Brocades from Ahmedabad and centres like Chanderi, Maheshwar and Pune made their mark on the Bombay landscape.”

Thana, or Sristhanaka, the North Konkan capital for the Chalukyas of Vatapi (now Badami), enjoyed flourishing trade activity routed through it as early as the first century. Consequently, crafts thrived around the region, with access to markets and higher revenues possible. Even the Pope’s vestments were woven from Thana silk. The city’s status as such a vital commercial hub continued till the British took over the seven islands.

“Shock, awe, despair” is how Suri chooses to share reactions to cloth swatches displayed at the Textile Manufacturers of India exhibition she presented last year in the Durbar Hall of the ASM. “Shock that hand-weaving existed until 100 years ago in Thana, unbelievable in today’s public imagination. Awe at the quality of work. Despair at the tragic loss of it all. The loss is greater for textile historians. Most of this remains undocumented. Till we saw the swatches in Watson’s catalogue, we did not know or take it seriously.”

A Mahabharata jewel

Aranyaka Parvan of the Mahabharata, the 16th-century illustrated Sanskrit manuscript

Aranyaka Parvan of the Mahabharata, the 16th-century illustrated Sanskrit manuscript

Another lustrous gem of a manuscript, among several of its kind in the ASM, is the Aranyaka Parvan of the Mahabharata. Valuable despite nearly one-third of the folios missing, its contextual focus traces the events during the Pandavas’ twelve years of exile following Yudhishthira’s defeat at the game of dice.

In a monograph published by the Society in 1974—An Illustrated Aranyaka Parvan in the Asiatic Society of Bombay—authors Karl Khandalavala, then Chairman of the Prince of Wales Museum, and Moti Chandra, Director of the Museum, write: “The Aranyaka Parvan has proved to be the most outstanding discovery of recent times for the study of sixteenth-century Indian miniature paintings of the pre-Mughal school. This manuscript belongs to a separate collection in possession of the Asiatic Society of Bombay known as ‘the Dr Bhau Daji Memorial Collection’.”

Master of the “Great Game”

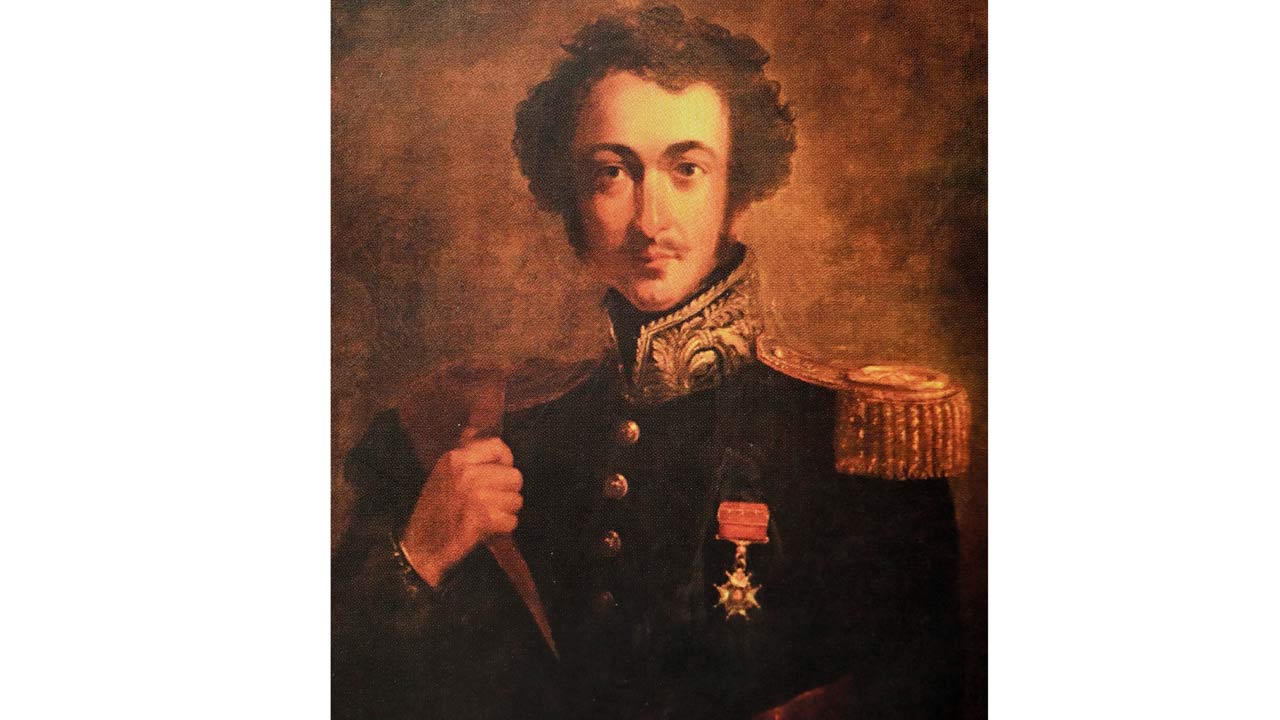

A rare portrait of Sir Alexander Burnes in uniform

A rare portrait of Sir Alexander Burnes in uniform

A unique portrait of military man, diplomat, secret agent and explorer Sir Alexander Burnes (1805-1841) was gifted to the Mumbai branch of the Royal Asiatic Society by the Bombay Geographical Society. Considered the only image in uniform of the extraordinarily charismatic—if controversial—officer, the painter-inventor William Brockedon’s unusual frame shows Burnes about to remove his red-lined Bokharan robe to reveal the British uniform underneath.

Associated with the “Great Game” confrontation between Britain and Russia over Afghanistan and neighbouring territories, in 1834 Burnes published his Map of Central Asia and Travels into Bokhara. “His skill was political insight; he was able to understand complex situations and grasp salient points,” writes Craig Murray in Sikunder Burnes: Master of the Great Game—a book historian William Dalrymple hails as “an important re-evaluation of this most intriguing figure”.

Burnes was the proverbial bad boy, universally attractive to women. With adventures less condemned in racy fiction than in sober biography, he appears to have consistently indulged in rather reckless sexual peccadilloes. Hacked to death by a mob in Kabul, he has neither a grave nor a memorial.

Manuscript magnificence

The original manuscript of Dante’s 14th-century epic, Divine Comedy

The original manuscript of Dante’s 14th-century epic, Divine Comedy

The shining star among the ASM collections is one of two oldest surviving manuscripts of a classic European text; the other lies in Milan. The Italian poet Dante Alighieri’s epic La Divina Commedia (Divine Comedy) dated 1350, a silk-wrapped medieval tome richly studded with 450 illustrated pages, very occasionally goes on display.

Ishaan Tharoor wrote, in a January 2009 issue of Time magazine, of how the evocative verses featuring the passage of man’s soul through the three after-death stages of Inferno (Hell), Purgatorio (Purgatory) and Paradiso (Heaven), “came to Mumbai in the possession of a 19th-century British antiquarian grandee, the imperially named Mountstuart Elphinstone, and has stayed in the city, despite numerous attempts by the Italian government to repatriate it.”

It is widely reported that in the 1930s, trying to cultivate a “cultured” impression to counter his fascist persona, dictator Benito Mussolini promised the Society one million pounds for the return of this priceless first edition copy. The offer was politely declined.

Author-publisher Meher Marfatia writes fortnightly on everything that makes her love Mumbai and adore Bombay. You can reach her at meher.marfatia@mid-day.com/www.meher marfatia.com

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!