Linguist-writer Sachin Ketkar contributes to a new book which outlines the aesthetic infused by Eliot’s defining poem into the Marathi literary cosmos

TS Eliot’s The Waste Land is imbued with Sanskrit references. Apart from ending with the refrain Shantih Shantih Shantih, Eliot also refers to three other alliterative Sanskrit terms—datta (charity), damyata (compassion) and dayadvam (self-control) in the masterpiece. Pic/Getty Images

![]() The final section of TS Eliot’s 434-line epoch-making poem The Waste Land ends with a reference to a thunder crack and the Sanskrit refrain Shantih Shantih Shantih. Eliot refers to three other alliterative Sanskrit terms—datta (charity), damyata (compassion) and dayadvam (self-control), which give rise to the “Da Da Da” sound of thunderous rain. These references have evoked curiosity about Eliot’s study of Sanskrit texts.

The final section of TS Eliot’s 434-line epoch-making poem The Waste Land ends with a reference to a thunder crack and the Sanskrit refrain Shantih Shantih Shantih. Eliot refers to three other alliterative Sanskrit terms—datta (charity), damyata (compassion) and dayadvam (self-control), which give rise to the “Da Da Da” sound of thunderous rain. These references have evoked curiosity about Eliot’s study of Sanskrit texts.

ADVERTISEMENT

It triggered in depth critical analysis ever since the modernist poem was published in 1922—four years after the end of World War I. Indian critics and academia were particularly appreciative of the influence of Bhagavad Gita and Upanishads on Eliot. The newly-released slim volume, 100 Years of The Waste Land: Indian Responses (Orient BlackSwan), captures the Indian excitement over Eliot’s recourse to Hindu texts in his search for ultimate durable peace (shantih) in a landscape marked by post-war loss, desolation and urban chaos.

The first chapter by the Baroda-based linguist-translator-poet Sachin Ketkar outlines the social context in which Marathi literati reacted to Eliot’s canon. Ketkar is the editor of the acclaimed Live Update: An Anthology of Recent Marathi Poetry (2004); winner of the Indian Literature Poetry Translation Prize (2000); and professor of English in MSU Baroda. His contribution to 100 Years of The Waste Land is crucial because as a critic and a poet, he has a nuanced understanding of “the effective life” enjoyed by Eliot’s ideas in Marathi poetry spanning eight decades. He presents an eclectic mix of poets, who were impacted by Eliot’s imagery and free verse; three litterateurs (PS Rege, Vilas Sarang, and Mahesh Elkunchwar—credited with dissimilar works) explicitly expressed their debt to Eliot (1888-1965). Playwright Elkunchwar says it with immense gratitude: The Waste Land is less of a pastiche, a complex and sublime philosophical poem with many levels of meanings that unfold as we re-read it... it stands like a pillar of light in the bloody and tempestuous history of the 20th century.

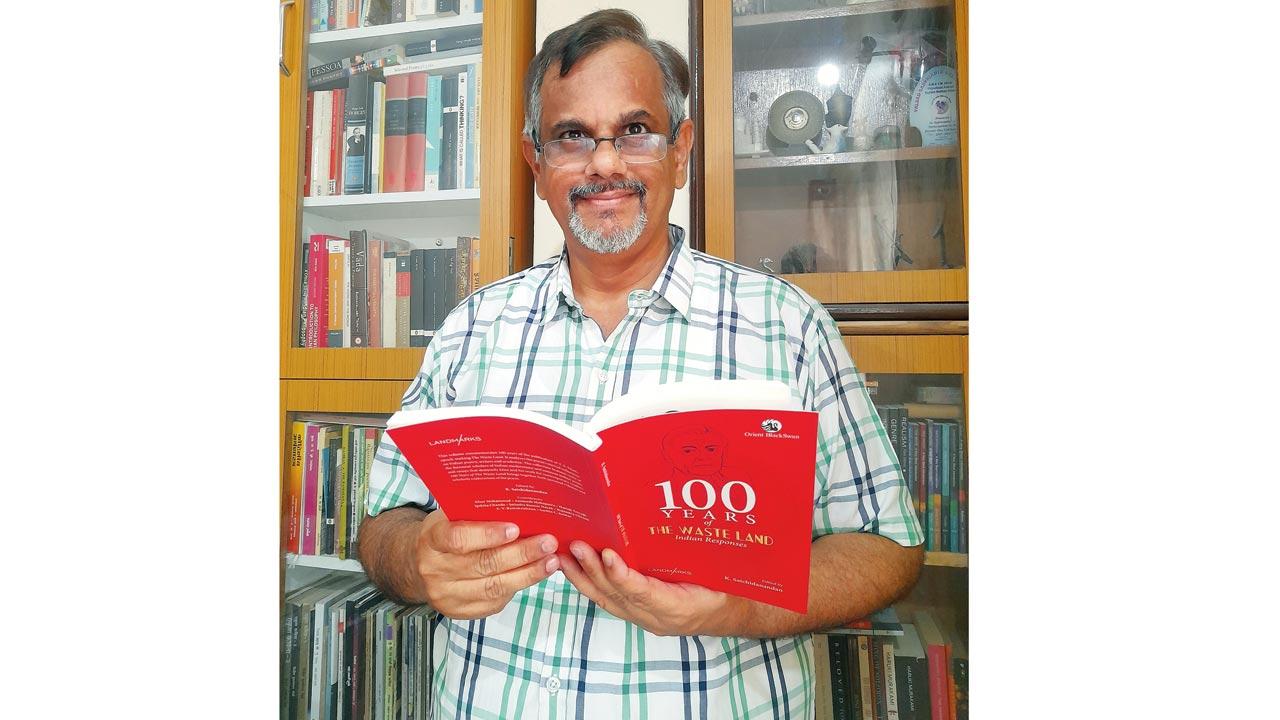

Sachin Ketkar

Sachin Ketkar

Ketkar zeroes in on an interesting untranslatable aspect of The Waste Land’s complex idiom—In this decayed hole among the mountains/In the faint moonlight, the grass is singing. A full-fledged Marathi translation of the poem came as late as 2019 by Purshottam Deshmukh; which many term as annotated explanatory text than a translation. Vilas Sarang, who translated select Eliot pieces for his book Bhashantar Ani Bhasha, says the poet’s primary accomplishment is the invention of the non-rational logic of imagination as against logical tight structures of the preceding poets. Sarang elaborates on Eliot’s peculiar word order, subject-verb-object, while subject-object-verb is the norm in Marathi. For instance, “He, the young man carbuncular, arrives/A small house agent’s clerk, with one bold stare, One of the low on whom assurance sits. As a silk hat on a Bradford millionaire.” Eliot is referring to a pimply-faced kid, way too self-assured, with a pathetic job and a boring girlfriend. It is not just difficult to adapt the poetic texture in the Marathi lingo, but it is difficult to process the pop-culture references strewn in every line. What does one make of Mr Eugenides, the Smyrna merchant Unshaven... and the demotic French.

While Indian cultural equivalent phrases for Eliot’s London references are difficult to locate, his themes of urban despair, absurdity and destruction, however, find an echo. The works of Marathi writers of the early 20th century, specifically Bal Sitaram Mardhekar, who died young at 46, comes closest to Eliot’s idea of avant-garde modernist writing. In his short eventful life, Mardhekar spent four years in England. In an earlier paper titled, Laughing Skeletons and Aging Metaphors: Theorising the Modernist Avant-Garde in Marathi, Ketkar writes about “the dark surreal imagery” of Mardhekar’s Laughing Skeletons (refers to the Marathi title Haadanche Saaple Haasati).

Mardhekar, in a poem, is very unsentimental about the excitement of lovemaking. The poem points to “the gaping holes where their genitals would have been”. It is the language of western avant-garde. Mardhekar was pulled in a court of law on obscenity charges, though also declared innocent later.

In fact Mardhekar’s “explicit evocation of sexual frustration, hybridised Marathi and rather quaint use of the traditional Bhakti poetics” later reflected in the works of Arun Kolatkar, Dilip Chitre and Namdeo Dhasal. Mardhekar, therefore, is a defining poet with links not just to Eliot’s canon, but also other Marathi poets who overthrew clichés. It is reported that Mardhekar met Eliot; some say he shared an English manuscript with the latter. But the documented evidence of the meeting is unavailable; yet that does not take away from the fact that Mardhekar’s works underscore the phenomenon of English-Marathi bilingualism and its relationship with modernism. Ketkar points to bilingual writers such as Arun Kolatkar (1932-2004), Dilip Chitre (1938-2009), Vilas Sarang (1942-2015), Gauri Deshpande (1942-2003) and Kiran Nagarkar (1942-2019) who played a considerable role in establishing modernism in Marathi literature as well as in Indian writing in English. “These writers, Mardhekar included, are deeply connected to the urban metropolitan setting of Mumbai. The pervasive and decisive presence of urban life in the avant-gardes across the world can also be understood in cultural semiotic terms,” Ketkar explains.

Ketkar makes a special mention of Arun Kolatkar’s early Marathi poetry, which was “intensely dark, unsettlingly subjective, and surreal” termed as “kalya kavita”. These dark poems are the types which Eliot, in his essay Three Voices of Poetry (1953), termed as the poems of the first voice—the one that is addressed to no one in particular, and is a result of the intense struggle between the poet and his unknown dark psychic material. Metaphysical angst, depression, and existential sense of absurdity found in the early modernist poetry in India are abundantly found here, Ketkar feels.

He further adds that for Eliot the poetry of the second voice is that of the poet addressing an audience, and the poetry of the third voice is when the poet creates an imaginary dramatic character addressing another imaginary dramatic character. Kolatkar’s poetry of Sarpa Satra, Kala Ghoda Poems, Bhijki Vahi, Chirimiri and Jejuri belong to these voices.

Apart from the Marathi poets’ responses, 100 Years Of The Waste Land (edited by critic-playwright-poet K Satchidanandan), also factors in other Indian language responses. For instance, Odia poets like Guruprasad Mohanty and Bhanuji Rao reinvented their idiom due to the influence of Baudelaire and Eliot. The Odia translation of The Waste Land (Poda Bhuin) came in 1956, and carried Eliot’s letter of appreciation. It is another story that some Odia critics felt the rendering didn’t carry the culture of the original.

In Bangla, Eliot deepened and widened the understanding of pioneer poets who saw the reflection of the burgeoning London in a Calcutta of beggars and refugees. For many poets in Kannada, Eliot’s The Love Song of J Alfred Prufrock was “their rite of passage to modernity”. Poets like Gopalakrishna Adiga, who inaugurated the Navya literary modernist phase in Kannada, could be understood by students only “through an obligatory initiation into Eliot and Auden’s poetry”. In Telugu, senior poets like Pattabhi and Aluri Bairagi used free verse forms and unknown urban metaphors, much influenced by The Waste Land’s metric experiments.

Editor Satchidanandan admits The Waste Land impacted many Indian litterateurs who are unrepresented in the current discourse, like Sitanshu Yashaschandra (Gujarati) and Abdul Rehman Rahi (Kashmiri).

The Waste Land has a variety of Indian fans-poets who swear by each line of the epic poem. But Delhi University Professor-translator Harish Trivedi, who explores the work’s English-American dimensions, finds it pretentious. Trivedi feels Indians, still under a colonial hangover, are unduly impressed by Eliot’s superficial use of Sanskrit. It is amusing that Trivedi’s harsh critique of Eliot’s Orientalist-Sanskritic Indian references, goes close to Marathi writer PS Rege’s sarcasm over the Indian critic’s jubilation for Eliot’s reliance on the Oriental philosophies. Rege felt Eliot’s idea of tradition was not fluid, but marked by geo-cultural boundaries. His reliance on Upanishads, Bhagavad Gita and Buddhism are held as signs of cultural conservatism.

In 2023, over 100 years after the poem was written, we can reread it, to see if it guides us in any other way.

Sumedha Raikar-Mhatre is a culture columnist in search of the sub-text. You can reach her at sumedha.raikar@mid-day.com

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!