As Mumbai rounds off four days of Fashion Week, conversations hinged on endless showstopper twirls and looks more than a wardrobe of personal usership. Sigh. Somebody please remind them, with sartorial power comes great responsibility

Kriti Tula’s label Doodlage invoked ’90s nostalgia of circularity practiced in Indian households when every garment was loved, cared and repaired

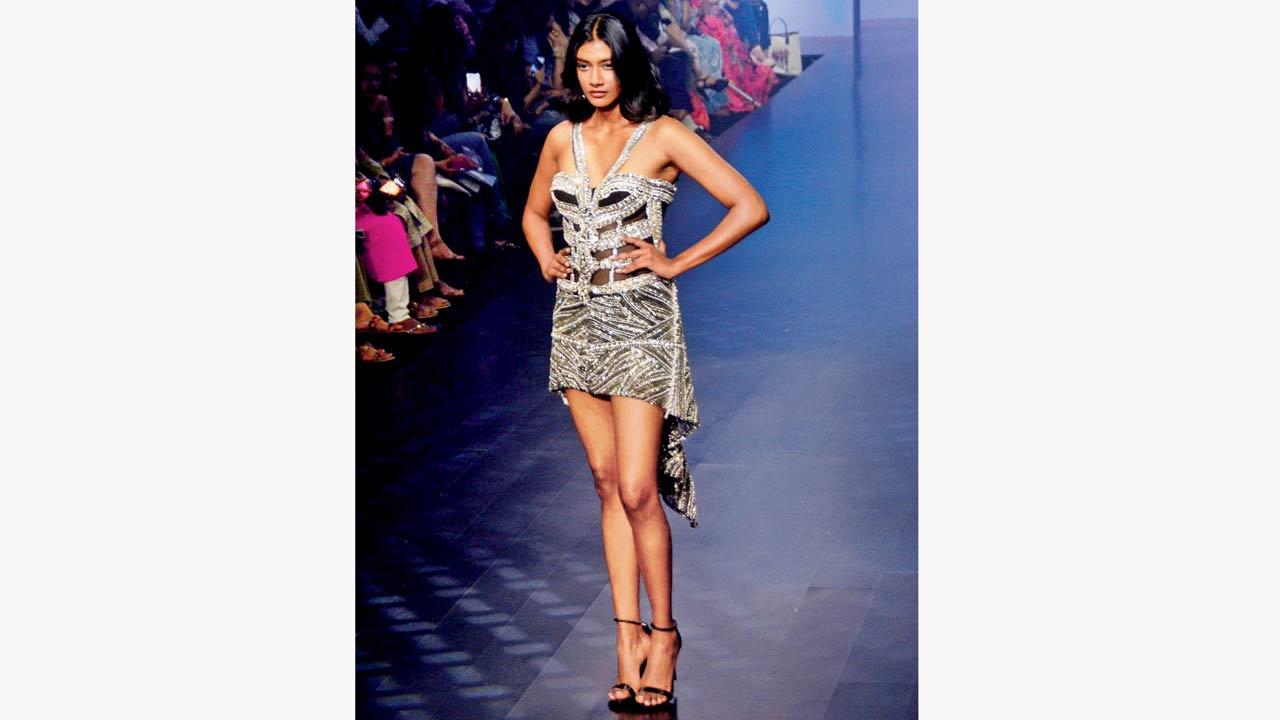

You can tell that fashion week has changed, because the people in its vicinity look different. Lakmé Fashion Week in partnership with FDCI, is a biannual event when designers showcase their collections and set the big, wild mood for the season ahead. Also in the spotlight are concerns about the environmental impact of clothing.

You can tell that fashion week has changed, because the people in its vicinity look different. Lakmé Fashion Week in partnership with FDCI, is a biannual event when designers showcase their collections and set the big, wild mood for the season ahead. Also in the spotlight are concerns about the environmental impact of clothing.

ADVERTISEMENT

But as realities of the climate crisis become more real—the event was held during unusually warm and humid days of early March—the takeaways from the recently concluded season signalled mixed flags. After positioning itself as a “catalyst of conscious fashion ecosystem” for over a decade, the event’s commitment to “sustainability” faced a strange repudiation when highlights from the collections, especially by senior designers, hinged largely on a display of excess—in form, content and social entertainment.

Pic Courtesy/Maria Issa

Pic Courtesy/Maria Issa

One person’s sustainable style is another’s unethical outrage. What is shown on the runway directly influences what you wear. That is the whole point. That is literally what makes fashion. Otherwise, we are just talking about clothes. Wouldn’t a little pruning, prudence, a little more discretion with regards to “not everyone who designs a hoodie or lehenga should have a runway show” have solved the quandary of how to make and wear fashion with low-environmental impact?

“Ten years ago, we were timid about talking about creating clothes from deadstock. Today, it is a conversation starter. The idea of repurposing waste fabrics that would otherwise clog landfills is now appreciated,” says Kriti Tula, creative director at Doodlage, a label founded on the principles of recycle, repair and rewear. Her collection titled, Nostalgia, showcased on Sustainable Fashion Day combined practical and civilised shapes of shift dresses, trench coats, drawstring shirts and jackets in recycled denim and deadstock handloom fabrics with child-like floral prints, influencing the uniqueness of each piece. Although the collection was structured as a dialogue on circular design, its strength was its simplicity.

Mumbai designer Saisha Shinde finds lateral thinking a promising business model. Along with utilising excess stock, she is also rethinking how to extend the lifespan of the existing garments, because “designing is fundamentally problem-solving”. This was seen in the range of 20 occasion wear pieces, including billowing empire-line gowns, full-skirted cocktail-hour dresses, and particularly in the upcycling of an “unsold” outfit from 2020—an embellished jacket and trousers which she turned into an evening wear ensemble for her show last week. It was simple but ingenious. “For all the excitement around fashion week, the strain on both budgets and designers to make sense of this endless rush of the new, sensational and special [in retail jargon] leads to excess. The wardrobe fantasies of real women with jobs and families, who buy and not borrow clothes, are centred on well-designed and long-lasting clothes. And they are definitely not buying on whim or looking at garments to empower them,” says the designer.

While most star designers are still trying to hold a celebrity showstoppers’ hand in the newly accountable fashion industry, a generation of relatively younger and non-starry brands are offering pointed answers to what it means to be a person living in 2023. Designers like Anavila Misra, Gaurav Jai Gupta of Akaaro, Anvita Sharma of Two Point Two, Ujjawal Dubey of Antar-Agni, Iro Iro and Ruchika Sachdeva of Bodice focused on the real business of offering garments for the body and for the client’s life. It is thanks to them that fashion week touches the crux of today’s person. It is where the spotlight pivots to something more imaginative than a culture of transient looks. Maybe the best cutting-edge position to take today is that each of us can make fashion sustainable if we develop a personal style.

Saisha Shinde repurposed an “unsold” jacket-trousers outfit from a 2020 collection into an evening wear ensemble for her show last week. Pic/Satej Shinde

Saisha Shinde repurposed an “unsold” jacket-trousers outfit from a 2020 collection into an evening wear ensemble for her show last week. Pic/Satej Shinde

Ninety-million tons of textile waste is created every year, and the global fashion industry is responsible for 10 per cent of humanity’s carbon emissions, says the UN. Such shocking stats rightly highlight an urgent problem, but they don’t tell the whole story. Telling the stories of how it is cool to put the ethical onus on designers; we are letting ourselves, the consumers, off too easily if we shrug and expect event organisers to shoulder responsibility for the environmental consequences of our consumption. To make sense of the sustainability conundrum, you have to adopt Dame Vivienne Westwood’s “buy better, buy less” mantra, and then extend it as far as you can. “Philosophically, on a deeper level, it [sustainability] is all about the age-old jugaad culture. Make do with what you have,” journalist and sustainability activist Bandana Tewari says, describing her own personal style as “repeat chic”. “Every wardrobe is unique to its owner, containing a collection of clothes that acts as records of who we are. It is therefore deeply connected to individual sense of self and values.”

Fashion can be about many things but in the end it is always a space at the heart of contemporary culture and communication, and one that provides employment. “We are not saying don’t buy new things but ask yourself, how much do you really need each season?”

Gaurav Jai Gupta’s Sky is Mine Vol 2 is a continuation of his label Akaaro’s study of International Klein Blue. Pic/Anurag Ahire

Gaurav Jai Gupta’s Sky is Mine Vol 2 is a continuation of his label Akaaro’s study of International Klein Blue. Pic/Anurag Ahire

Trust your instincts instead of hustling over to Instagram and driving yourself nuts with influenced serial “lewks”. (To those as yet unenlightened, a lot of people you see on social platforms and those lining the front-row are either borrowing or endorsing trophy items rather than actually owning, wearing or loving them.)

The most attention-seeking statement you can make with your outfit is to signal that you have chosen it with a view of sending out vibes of who you are, and not because it is paid and pushed as super-trendy. If you are looking for a good place to start, Tewari suggests: “Ask yourself, how dependent are you on external validation of how you look, and whether it reflects who you are from the inside. Am I my own person, or am I about a look?”

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!