Branding pandit Kiran Khalap maps the intersections where Mumbaiu00c3u00a2u00c2u0080u00c2u0099s working class unites with its English-speaking elite

Author Kiran Khalap throws light on chawl inmates in his third work of fiction. Pic/Bipin Kokate

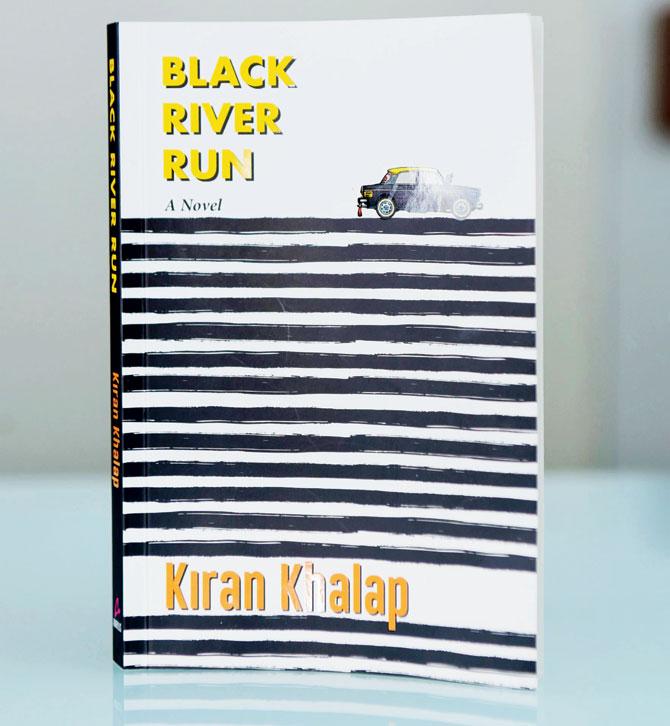

Actor Dev Anand singing Jayen To Jayen Kahan, in Navketan's film Taxi Driver, came to mind while leafing through branding expert Kiran Khalap's newly released Black River Run (Amaryllis publishers, R299, 184 pages) which is centered around a nearing 60 cabbie, driving a kaali peeli in a Mumbai pre-dating the advent of Olas and Ubers. Anand's Mangal and Khalap's Buva both mean well and try to lead positive lives, but get trapped in big city excesses. At the outset, both protagonists are comparable; they evoke respect. But, as Buva's narrative unfolds and his violent caste-ridden past is bared, his allegiance to 17th century saint Samarth Ramdas becomes a bit of a riddle. This columnist appreciates Buva's present, but is unable to envision the possibility of his deep identification with a saint.

Actor Dev Anand singing Jayen To Jayen Kahan, in Navketan's film Taxi Driver, came to mind while leafing through branding expert Kiran Khalap's newly released Black River Run (Amaryllis publishers, R299, 184 pages) which is centered around a nearing 60 cabbie, driving a kaali peeli in a Mumbai pre-dating the advent of Olas and Ubers. Anand's Mangal and Khalap's Buva both mean well and try to lead positive lives, but get trapped in big city excesses. At the outset, both protagonists are comparable; they evoke respect. But, as Buva's narrative unfolds and his violent caste-ridden past is bared, his allegiance to 17th century saint Samarth Ramdas becomes a bit of a riddle. This columnist appreciates Buva's present, but is unable to envision the possibility of his deep identification with a saint.

ADVERTISEMENT

Buva is a BDD Worli chawl resident who has migrated from remote Khairlanji; his pregnant mother was killed by upper caste men; he is haunted by bad memories; but he relies on Ramdas Swami's treatise Dasbodh (a manual for life) for answers to tricky situations. As a journalist, who has followed state caste politics and the 2006 Khairlanji massacre, I was wondering about the likely guides-mentors an untouchable orphan (who has fled to Mumbai in tense conditions) would fall back on in the contemporary context. I was looking for a more convincing backdrop for Buva's unlikely fondness for a known upper caste idol. While one acknowledges the fact that saints rise above parochial considerations, there is always a reason why their disciple base flourishes in respective social circles and geographies. In Buva's case, the reason is not clear. It is another fact that, even as a riddle, Buva is likeable. When jailed for a murder that he did not commit, he lives up to the quintessence of mokshabhimaan… ya naav bhram (the pride associated with the idea of liberation is an illusion). Like his mentor, he pays extreme importance to physical fitness, doing Surya Namaskars at the crack of dawn, even in prison. Khalap's fluid prose catches each namaskar with exemplary elasticity.

Black River Run looks at Mumbai through the lens of a Kaali Peeli taxi driver

Black River Run is an oblique gaze at Mumbai's manifold facets, riveting locales and colorful sub-cultures, shown through the lens of a taxi driver who yearns for detachment. In reality, Buva is attached to fellow chawl mates, needy passengers, trafficked minors, riot-affected victims and a cat which notices his absence. Without his own realisation, he is attached to his violent caste-ridden past and is unable to forgive upper caste forces. The novel is about the deep underlying animosity fuelled by religious and caste divisions that Indians have not been able to address. Even the seemingly peace-loving types, like Buva, explode with hatred at critical junctures. The black river, a symbol of irrational thinking, runs through usual and unfamiliar suspects—the less-educated, the well-to-do, the seemingly-enlightened and also

the underprivileged.

At the core of Khalap's third work of fiction—earlier titles are Halfway Up the Mountain, Two Pronouns And A Verb—lies his favourite theory about the disconnect (and connect) between India's working class and its English-speaking elite. For him, beauty lies in the manner in which dissimilar individuals and groups navigate their lives despite the cultural divide. Either as the founder of the chlorophyll branding-communications firm or as a speaker at London's Indie Summit, Khalap recurrently deliberates on the Eye Nation Versus Ear Nation. The Eye Nation pitches business proposals, replies via email, is seduced by Beethoven and M F Husain and wears spring-flower fragrances; the Ear Nation prefers heady attars. It has no patience for instruction manuals, it accepts communication in routine rhymed patterns—be it polio vaccine or tax reminders.

Khalap separates the Ear and the Eye in Black River Run. Buva, an endorsed resident of the Ear Nation, which represents 1.2 billion Indians, speaks in the mother tongue, follows the Indian calendar which prescribes days for vegetarian food, and determines driving speed and route as per the urgency (not Google maps) of the passengers. His life is inextricably linked to residents of English India, like olfactory scientist Jeroo Jeejebhoy or playwright Ramesh Joshi. Khalap shows how two 'Indias' intersect despite divisions.

Kiran Khalap, 61, is a great believer in intersections, he has joined distant dots that seem amusing in retrospect. On the day he finished the BSc course (chemistry) from Mumbai's SIES College in 1979, he took off to Benares to teach at a residential school run by the J Krishnamurti Foundation as he wanted to propagate the seer's values. After four years, he relocated to Mumbai and joined Lintas as a trainee copywriter and then became one of its youngest creative directors. He was later chosen to lead advertising agency Bates Clarion. In chlorophyll, the firm he founded, he has worked on 250-odd brands, from Meru Cabs to Infosys. He was part of the team that

created the brand strategy for the Unique Identification Authority of India. "The UIDAI is a rock-solid aadhaar for reaching maximum beneficiaries for any pro-people programme. For me, it was a sheer joy to be working on the world's largest biometric database."

Writing is another cathartic joy for the branding veteran. He catches up with his writing whenever he is alone, even on flights. His weekend pursuit of rock climbing, which he is very passionate about, never hinders writing deadlines. In fact, it is not the writing process, but the research, that took him four years to finish Black River Run. He interacted with 50-odd taxi drivers, accompanied them to their leisure addas, took to the routes on which they ferried members of the English Nation, and also inspected the innards of Fiat cars which house the cabbies. Understanding the world of khabris to sculpt his character Pakya was another exploration. Interestingly, it was real-life inspector Yeshwant Banda Phatak (acknowledged in the book) who reasoned out Buva's acquittal from the prison. A lawyer had concluded that Buva couldn't escape a lifelong term. "I didn't want to leave Buva trapped in a gory murder located in an ice cream freezer."

It is a coincidence that Black River Run is released at a time when the BDD Chawls are being demolished, but Kiran Khalap has been fascinated for long with the "amphitheater of arson and assassination." The chawl, a disappearing species of residence, is close to Khalap's heart since he was born in a 50-square feet room in Girgaum and later spent his childhood in a chawl at Prabhadevi. His cousins lived in Khotachiwadi which strengthened the 'chawl' bonding and became the hummus of his life. He was particularly introduced to BDD Worli by adman-friend Sekhar Chandrasekhar who lived there and whom Khalap dropped home after late night booze parties.

Originally designed as prisons for Indian freedom fighters, these converted residential tenements at Worli (a cluster of 121 buildings housing 1120 families) offer a puzzling variety—communal harmony and festivities (dahi handi) along with violence and caste riots since the 1970s. In terms of demographics too, the chawls' lower middle class constituents are varied—from the humble patrolman to the malkhamb enthusiast to the migrant labourer to the student studying under a streetlight.

For Khalap, literature is directed towards unification—bridging gaps in a world that is torn apart by divisions. He wants to be the unifier—somewhat echoing the Dasbodh essence of Nana Jananche Hriday, Mrudu Shabde Ukalave—through soothing words, unravel and alleviate diverse people's hearts.

Sumedha Raikar-Mhatre is a culture columnist in search of the sub-text. You can reach her at sumedha.raikar@gmail.com

Catch up on all the latest Crime, National, International and Hatke news here. Also download the new mid-day Android and iOS apps to get latest updates

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!