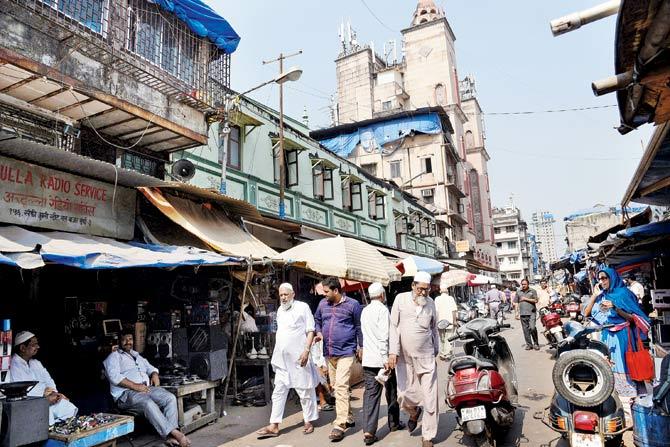

Old residents and shopkeepers of Bhendi Bazaar, now on the cusp of redevelopment, trace its heyday

Long view of Saifee Jubilee Street with the Handiwala Masjid (green facade) and Qutbi Masjid (pink facade) on the left. Pics/Shadab Khan

But what's left there?" astonished voices ask. I get incredulous looks when I share that Bhendi Bazaar holds a still amazing, if disappearing, universe. Over half its vast population waits in transit MHADA flats for what is touted as the city's most ambitious cluster rehabilitation. The dense precinct has long suffered appalling infrastructure, from no waste disposal system to rickety homes crashing with tragic regularity.

But what's left there?" astonished voices ask. I get incredulous looks when I share that Bhendi Bazaar holds a still amazing, if disappearing, universe. Over half its vast population waits in transit MHADA flats for what is touted as the city's most ambitious cluster rehabilitation. The dense precinct has long suffered appalling infrastructure, from no waste disposal system to rickety homes crashing with tragic regularity.

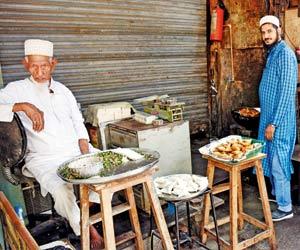

At their Diamond Samosawala shop, Hakimuddin and his son Burhanuddin have sold samosa pattis for 65 years, along with assorted kebabs, cutlets and kachoris

A multi-million makeover announced by the Saifee Burhani Upliftment Trust currently redevelops 250 buildings that are close to 80-100 years old. Returning residents are promised bigger homes with ownership and sanitation (tenant families squeeze into 150-square feet chawl rooms with a common toilet per floor).

A typical plate prepared by Diamond Samosawala

Stretching from the tail of Khetwadi along SVP Road till multitudinous Mohammedali Road, this precinct's proximity to the port and Crawford Market raised business hopes in the 1800s. Planned by colonial powers to decongest Fort district, it was the "native town", strewn with horse stables by 1840. Scaling culture with commerce, the 1890s birthed the Bhendi Bazaar music gharana, Manna Dey, Begum Akhtar, Lata Mangeshkar and Asha Bhosle among its exponents.

Hatimbhai sits at his Pakmodia Street medicine shop, Mulla Abdulhusain Bakri Malampatiwala, established by his ancestors in 1860. Pics/Atul Kamble

Bhendi Bazar isn't only a nod to Indian tulip tree groves (Thespesia populnea), locally called bhendi. Southside Brits described the area "behind the bazaar", which people colloquially slurred to Bhendi Bazaar. Dawoodi Bohras form its majority, tracing their original lineage to Yemenis trading with 11th-century India. From itinerant peddlers bearing bags of knick-knacks dubbed "chow-chow", the vicinity thrived as a wholesale, retail and antique market - Chor Bazaar famously opposite.

Nasreen Sayed and her brother Zafar Ahmed at Hamza Perfumers, the fragrance store they converted from their grandfather's Unani dawakhana

Nasreen Sayed and her brother Zafar Ahmed at Hamza Perfumers, the fragrance store they converted from their grandfather's Unani dawakhana

Gas lamps cropped up in the tenure of first Municipal Commissioner, Arthur Crawford, after whom the market is named. On October 7, 1865, Bhendi Bazaar migrants gasped at the novelty of sighting a lamp-lighter and trailed him through the warren of lanes. Conjuring the scene, I walk the Saifee Jubilee Street-Dhaboo Street-Pakmodia Street-Tokra Gully grid.

In this heartland of fasting and feasting, the faithful imbibe the purity of Ramzan, the piety of Muharram. Thousands rooted in tough conditions seek the infinite comfort of five mosques and the magnificent Raudat Tahera mausoleum. Within rest the present 53rd Syedna Mufaddal Saifuddin's grandfather, Syedna Taher Saifuddin, and father, Syedna Mohammed Burhanuddin. The 51st and 52nd Da'i al-Mutlaqs of the Bohras are so revered, a daily trip to their tombs is de rigueur honour.

A 772-page handwritten Quran from which Syedna Taher Saifuddin recited is entirely copied on marble slabs. Verses inlaid with gold leaf, significant revelations like "Bismillah" are bejewelled. Raudat Tahera is distinctive for this unique calligraphic feat - the world's sole site embedding a complete sacred book in its sanctum sanctorum. The dome proclaims: "Allah holds the sky and earth together which none else can."

In his 1863 book, Mumbaiche Varnan, the Marathi writer GN Madgaokar observed that at Bhendi Bazaar inns called bhatiyarkhanas, "Arabs, Mughals and other Muslim travellers buy food worth two to four annas each day". Washing down shami kababs with sherbet, my Bhendi Bazaar thoroughbred friend Rashida Johar says, "The gastronomic delights of Pakmodia Street gave us iron-lined stomachs. Ripping whole sugarcane with our teeth, we gorged on chana-batata, ragda, kulfi, baraf gola, candy floss. For a few extra paise, the man pulling sticky, multi-coloured candy off a pole swirled intricate designs with it, the favourite being a watch of candy around the wrist which we licked off."

Rashida's mother often lowered a basket, called jambil, from Gandhi Building, for A.T. Bakery to fill. After feeding folks their staple bread, butter and biscuits, Hasan Pavwala reinvented the trade of his father Abdeali and grandfather Taiyabali (the A and T) from 1958. He stocks typical Bohra paraphernalia, kunli - the support a meal thaal rests on, to chaakhri - knob-toe plastic or steel bathroom clogs resembling Buddhist paduka sandals.

At 96-year-old Noor Sweets on Saifee Jubilee Street, Rashida's maternal uncle Abdiali Hasanali Mithaiwala promptly packs us boxes of soft doodhi halwa. With brothers Nooruddin and Yunus, he carries on after father Hasanali Alibhai, who fled Kotda Sangani village in Gujarat as a lad of 13 to work in Bombay. Just across, Hakimuddin and son Burhanuddin, of Diamond Samosawala, oblige customers who bring home-mixed mince and onion stuffing for them to fold neat patti strips around. "We've done this for 65 years, even supplied to the Taj," says Hakimuddin, wizened face flushed happy.

Stepping into parallel Pakmodia Street, I see 1860-established Mulla Abdulhusain Bakri Malampatiwala. Pointing to powders, tinctures and creams, Hatimbhai (the "Bakri" attached because founder-proprietor grandfather Abdulhusain was gentle as a lamb) assures me and Rashida's tourist guide cousin Tasneem Chitalwala that he has sure cures for boils, ulcers, psoriasis, piles and menopause problems. Fifth-generation nephews helping on the job, he says, "This is God's gift."

Past Taiyebiyah School, Lallubhai Mali Suratwala Florist has decorated wedding halls for long, beside Fakhri Farsan Mart from 1952. Twinkle-eyed Mohammed Dhorajiwala, of Taherally Peppermintwala, talks about the tiny thimble of a stall opened 80 years ago by his father Taherally. "It was crammed with 1001 items, A to Z," he says, as children lisp orders for stationery and sweets at "Taherkaka Pippermeet ni Dukaan".

Further in, Shabbir Paghdiwala and his son Tamim specialise in headgear for exalted elders "including His Holiness". Patronised by royal clans, they create the Al Mashaekh paghdi and Yemeni pheta. Adamji Paghdiwala's 1902 initiative was followed by his son Dawoodbhai, Shabbir's father. "Safai - neatness - is the quality to stay ahead in our work," Shabbir says.

Above the Paghdiwalas was the road's whisper-hushed address. The lane's charms were subdued by shor-sharaaba and shootouts stemming from the 33 Pakmodia Street pad of mafia don Dawood Ibrahim. Witnessing enough wars in D Gang territory, an elderly gent says, "Pizza chains refused deliveries and our girls weren't offered good marriage proposals." Tax consultant Ali Asghar Rangwala agrees the barricades and bandobast were too bad to tolerate - "Anyone entering the lane was suspected a killer. We have lived with fear, filth and encroachment. These issues must improve."

Leaving the blistering innards of Bhendi Bazaar, I spend a calmer afternoon with Abdiali Mithaiwala's sisters in their temporary quarters at Ghodapdeo near Cotton Green station (Mazgaon and Chunabhatti have other transit apartments). Sarah Mithaiwala, Fizza Dhariwala and Bilkis Chitalwala swap mohalla memories. "Sarafalibhai tangawala would ask us to throw down a chaddar as our veil-screen when his Victoria curtain was missing," says Dhariwala. "The only ones with a grinding stone, we were always pounding masalas for Parekh Building neighbours," remembers Chitalwala. Mithaiwala, the Corporator of Bhendi Bazaar from 1992-'97, says spiritedly, "I was the pucca tomboy of a conservative society, climbing trees, cycling and flying kites in pants beneath my dress, to our mother's despair." The sisters mention an interesting social gathering around the peti, a two-sectioned box outside front doors. Containing half ash and half sawdust to clean kitchen vessels, petis formed cheery meeting points. Men caught up with each other in long loo queues.

Back in Bhendi Bazaar alleys, I hear more women's stories from Agha Building and Patkar Manzil. Feisty 82-year-old Salf Bibi changes three buses from Juhu Koliwada to reach her gems store. Born in Bandar Abbas in south Iran, she sits at this counter her father-in-law Usman Zaveri introduced her to 60 years ago. "We match stones to astral fortunes. This is a bad phase for dhandha paani," she says, brown eyes flashing to the glint of her nose ring.

At Hamza Perfumers, clients of Nasreen Sayed and her brother Zafar Ahmed sniff flamboyant fragrances from cut-glass bottles. This was the Unani dawakhana of their grandfather Ghulam Nabi Ahmed, zamindar and hakim from Unnao in Uttar Pradesh. His son Manzoor practised till the 1980s when his children used the space to sell scents.

Nasreen's neighbour Tarannum Khan claims a sliver of cinema history. Dilip Kumar grew up next door to her mother Farida. Her father, Mohammed Ilyas Khan of Bhopal, became Saira Banu's secretary. Farida's father, Urdu theatre doyen Dr Abdul Alim Nami, was also Censor Board president. "Raj Kapoor visited my Nana, pleading he shouldn't cut Bol Radha Bol from Sangam," Tarannum says. That 1964 film song showed Kapoor woo Vyjayanthimala in a red swimming costume. Leading ladies did don wetsuits but this perhaps struck a colour era first. Retained, the number proved a Shankar-Jaikishan hit.

Dust flies thick from cranes at the spot where it all began for Adamis of Colaba Causeway. Ishaq and Yakoob Chamdawala are in their Gujar Street head office a week after their home round the corner was razed. Leaving ancestral Ujjain around 1910, their father Rasulbhai Adamji dabbled in hardware before selling leather. "Wallets and bags we marketed from 1965 were popular with foreign airline crews, particularly Alitalia and Iberia," says Ishaq, explaining why they speak Italian and Spanish. "As boys we enjoyed inter-lane cricket and kabaddi" Yakoob recalls. Quickly adding, "But, sentiment shouldn't count in the new development scheme."

Will community intimacy be buried by renovation rubble? Won't the project axe traditional trades best plied on open roads? Will Pakmodia Street shed notoriety with towers shining it unrecognisable? Its romantic Arabian Nights mosaic cracks day by day. Yet, Bhendi Bazaar could breathe once more.

Author-publisher Meher Marfatia writes fortnightly on everything that makes her love Mumbai and adore Bombay. You can reach her at mehermarfatia@gmail.com

Catch up on all the latest Mumbai, National and International news here

Download the new mid-day Android and iOS apps to get updates on all the latest and trending stories on the go

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!