mid-day newsroom stalwarts rewind to life in the '90s when the Internet was alien, the cell phone non-existent, a newsbreak did not depend on Twitter and journalists hadn't turned corporate

ADVERTISEMENT

The telephone book was an object of desire

Looking back at the mid-day newsroom of the '90s is poignant but not without pain, simply because turning back so far behind gives me a crick in the neck. It was a time of no mobile phones, and that meant the newsroom's one telephone book contained numbers of every famous and controversial person there was.

This book was frayed of cover, dog-eared and chai-stained. It was a yellowing piece of treasure, and zealously guarded. Colleagues about to leave the workplace for a competition paper would whisk it away for an hour when nobody was likely to feel its absence, to photocopy it in entirety.

Meanwhile, the shrill trill of landlines created a din all day. Photographs that we now access in our digital image archive used to be physical prints stored in brown folders in a musty library. The photographers had a 'dark' room where they developed their prints. It was a little hideaway for the men with the lens who used to quaff chai there, occasionally catnap too.

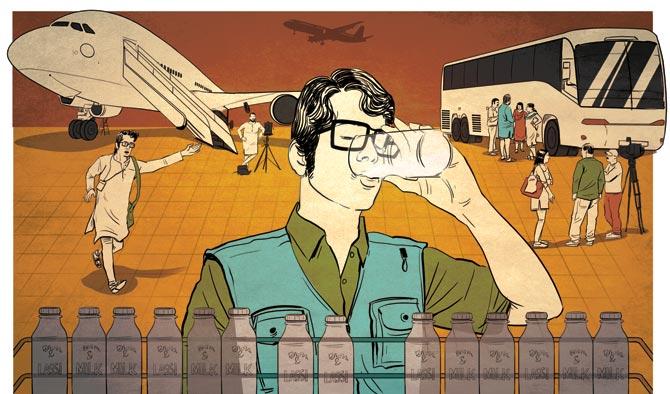

In the no tech era, it was about hits and misses. A reporter was once sent to the international airport late at night to talk to the Indian cricket team players returning from an international tour. Security was not as tight as it is now, and players, far more accessible. The team landed and exited from the airport but the reporter was not on scene. The team got into the team bus and the vehicle chugged. A young man was seen haring after the India bus for a few seconds before giving up the chase. The reporter was drinking lassi at a milk booth and the team had got away!

The result: a barging by the boss, peppered with cuss words, and other unprintables, which were all part of the newsroom lingo then.

- Hemal Ashar

No bigger newsbreak source than a person

I began my career as a cub reporter for mid-day in 1997, when the office landline or a PCO was your only tool of communication.

Since the telephone was a journalist's lifeline, that metallic one rupee orb was valued and I learnt never to leave home without it.

Once, I was told I had to 'cover a fire'. Excited and bushy tailed, I landed at a tea stall in Vikroli Parksite. The stall was gutted, but the casualty was nothing more than a sugar bag weighing 25 kg!

Rushing to Vikhroli in an autorickshaw was a luxury since I was on a monthly stipend of R300. Nevertheless, I filed the story and faxed it to the newsroom. It was never published.

The '90s taught me lessons for life — that there is no substitute for being on field. You have to earn your byline the hard way. Bylines were a luxury those days and only the city head or chief sub editor took the call on whether the story merited a byline.

A Page One story was both an adrenalin pumping achievement and a morale booster. This was the ultimate feather in the cap, since Page One would get displayed on the newsroom notice board.

We were constantly told about upholding the ethics and remembering the basics of journalism — the five Ws (What, When, Where, Why, Who) and the one H (How). Visuals were a 'must' for all stories and we had to have a Kodak camera with the roll. I learnt to take pictures for my own stories.

These were the bread 'n' butter basics that we were supposed to brand on our heart. Meanwhile, I have realised that hours spent doing seemingly “nothing” at hospitals, morgues and police stations help build contacts that one can dip into years after. Even chaiwallahs and shoe shine boys can give you a clue or two for your next big story. Technology may race ahead, but it is this human angle to journalism that has, and will continue to survive the digital age.

- Vinod Kumar Menon

mid-day was published from... was that an office?

Writers banging away at their word processors with a cigarette in between their lips; the chaiwalla leaving a glass of tea on your table every 45 minutes; galleys (bromides) scattered all over; choosing a different seat every day because we weren't privileged to have a designated work station -- we witnessed all of this in the newsroom of the 1990s, the last years of the hip era of journalism.

We are in Bandra today; back then, the mid-day newsroom was in Tardeo, a blink and you could miss it, one-storey structure, tucked away to the side of a taller office building. This was before newspaper offices began resembling swank, corporate hubs. We reached our unpretentious abode by climbing an iron staircase. Below the stairwell, boys were arranging papers into bundles.

We had to hop, skip 'n' jump over them to access the staircase. Once inside, the smell of ink from the printing press below wafted up.

There was humour, a lot of it caused by leg-pulling. And every mid-dayite who stayed long enough with the organisation was the target of a prank.

My favourite anecdote is about a sports reporter managing to fool his colleague with a memo from the Managing Director (MD) for a blunder. A few minutes later, the MD walked in and my disconsolate colleague apologised profusely. MD had no idea what she was talking about, but there was one pale person in the room — the prankster. That heart-in-the-mouth moment though, did not stop him from landing his next prey.

- Clayton Murzello

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!