Moving a few cricket matches out of Maharashtra might ease our conscience but won’t make up for years of water misuse in the state

Water, said a notorious CEO of a large multinational corporation, is not a human right and it should not be free. Much as his comments received — and rightly so — much anger and disgust, the fact is that the way we are going, water is no longer going to be either free or a right. It is going to be an expensive, elusive commodity.

Water, said a notorious CEO of a large multinational corporation, is not a human right and it should not be free. Much as his comments received — and rightly so — much anger and disgust, the fact is that the way we are going, water is no longer going to be either free or a right. It is going to be an expensive, elusive commodity.

ADVERTISEMENT

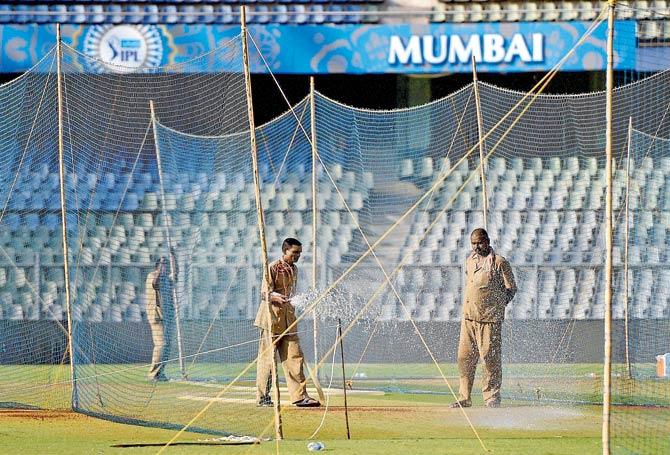

Groundsmen water the pitch at the Wankhede stadium ahead of the opening IPL match that took place on April 9 in Mumbai. The Bombay High Court is currently hearing a PIL over the wastage of water for the tournament. Pic/PTI

The current fight in India of a cricket tournament versus a drought may be well-meaning but it is bogus. Whether the IPL is held or not, whether it is moved out of the state or not, Maharashtra’s water problems will not vanish and nor will the current drought conditions. We are looking at years of sustained water misuse, of flawed water policies, of bad irrigation ideas and under-implementation of irrigation schemes. Moving a few cricket matches out to other parts of India may assuage a few consciences that feel water is being wasted on a cricket ground but far more than that is required.

Many experts are now pointing to how sugarcane as a crop is partly to blame for Maharashtra’s problems or those of any area in India that grows sugarcane. Some suggest growing pulses or vegetables instead. Another option is sugar beet which apparently grows in less time and uses much less water than sugarcane. It also leaves fields usable for other crops the rest of the time. We have heard how sugar lobbies are to blame for going slow on this and we all know how sugar lobbies practically control politics in Maharashtra at least.

But even this is just one part of the problem. Studies published last year using NASA satellite data revealed that India showed the largest ground water depletion in the world after the Arabian aquifer. Groundwater was disappearing without being recharged. This is a pattern being repeated across the planet. The problem is much bigger than an annual cricket tournament. A real fear is that once the IPL issue dies down, we will forget about the disaster around water and move on.

And yet, how lackadaisical are we and our governments about simple things like rooftop rainwater harvesting. It takes an initial investment, yes, but it pays back quite fast. All that water that flows down along concretised roads and into drains and into the sea — it is water that is lost for use. All it takes on an even simpler level is not to pave every bit of open ground. To leave some earth around trees and around roads and even more importantly, to stop building over existing water bodies.

Small sewage treatment plants in building complexes and neighbourhoods may help so that retreated water can be used to water plants — as happens in many sports grounds across the world. Human activity is water-intensive. And yet, sometimes it’s as simple as not cutting down so many trees, not turning all of nature into a concrete pile and not cementing every single bit of open land.

The fight is not just in big cities, it is not just in drought-prone areas, it has even spread to areas which were once water-rich. And in a country like India, which depends so heavily on the monsoon, the past three years of insufficient rainfall have been disastrous as we can see. But in spite of all the environmental awareness around us and information being thrown at us, we seem unable to be strong enough to buckle down and indeed, buckle up.

My childhood in Mumbai, I remember being about that welcome gurgle of water from a dry tap. Now we are so used to flowing water that we have forgotten the horrors of hand pumps and dry wells that still plague our fellow citizens. In some ways, you have to agree with the Shiv Sena when it says sarcastically that people have to be alive to chant ‘Bharat Mata ki jai’.

And yet, even with the Kerala temple fire — over 100 dead for a fireworks competition held without permission — we are more worried about popular sentiment than public safety. It’s as if symbolism and gimmickry are our escape routes when the problems around us are too big to handle. One can only hope that we do not have to wait for the next big water disaster to come to our senses.

Ranjona Banerji is a senior journalist. You can follow her on Twitter @ranjona

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!