A recent tweet by a former editor of this newspaper, Abhijit Majumder, got me thinking about journalism, and what it has come to represent in an era of social media, the Internet, blogs and 24-hour television

A recent tweet by a former editor of this newspaper, Abhijit Majumder, got me thinking about journalism, and what it has come to represent in an era of social media, the Internet, blogs and 24-hour television.

A recent tweet by a former editor of this newspaper, Abhijit Majumder, got me thinking about journalism, and what it has come to represent in an era of social media, the Internet, blogs and 24-hour television.

ADVERTISEMENT

This is what he said: “Some journalists are behaving as if the world would end if Modi wins. Do journalists elect, run governments? Or work heedless of storm, sunshine or a party?”

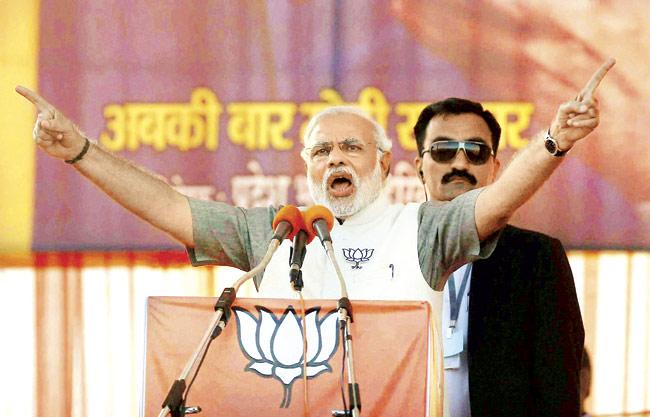

Abhijit is both wrong and right. Wrong because it is not just journalists who believe that a Narendra Modi-led government (with or without BJP’s NDA partners) will try to stifle the freedom of the press and expression.

There are instances where some editors have been asked to leave office on account of being ‘anti-Modi’, and these editors have gone on record saying the reason they were asked to leave was because the publishers ‘feared’ Modi.

And, of the former, there are instances where some editors have been asked to leave office on account of being “anti-Modi”. These editors have gone on record saying the reason they were asked to leave was because the publishers “feared” Modi.

But Abhijit is more right than wrong, because the strength of Indian journalism has never been slave to one person. Even during the Emergency (and there was no 24-hour television or the Internet at the time), some newspapers and magazines held out against a dictatorial prime minister.

We know, of course, what happened to Indira Gandhi and the Congress party in the 1977 elections. Democracy has a nagging habit of getting back at you if you try to violate its systems.

And so we come to 2014. Let’s assume, for the sake of argument, that Modi will form a BJP or a BJP-led NDA government after the election results are out in the third week of May. This is not a certainty, but indications are such that the Congress or a Congress-led government may not see the light of day next month.

Let us also assume that the arguments forwarded by some sections of the media — although we do not precisely know how Modi will behave once he becomes Prime Minister — that his government will try to stifle negative opinion may turn out to be true.

If both these scenarios play out in exactly the same way as predicted by some, then these two questions arise: Is Indian journalism so weak that it cannot withstand the forces of government suppression? Are our institutions so brittle that democracy may come to a standstill and no voice — bar the government’s, or Modi’s — will have any amplitude?

There is no gainsaying that Modi’s domination of administration in Gujarat has been near-absolute (try naming five of his cabinet ministers, for instance). It may not be the same in New Delhi, though. Democratic systems — and internal BJP dynamics — would most certainly prevent a domination of Modi, the person, over his cabinet and the rest of the administration.

The internal fissures in the BJP are not apparent right now because it is focused on winning the elections. We cannot predict what could happen once a Modi government is formed. If a Modi government does indeed attempt to stifle the press, it is up to the press to stymie that move and fight back.

There has hardly been any government anywhere in the world that has not tried to control the media. Even in countries such as the United States and the United Kingdom, there have been several instances where the administration has tried to force the hand of the media.

But they have consistently failed because the democratic institutions have been strong. In India, too, despite an absolute majority in the Lok Sabha, the Rajiv Gandhi government could not get the draconian Defamation Bill passed in 1988.

As recently as the last six months of 2013, the UPA government got more than 3,600 Facebook posts deleted presumably for being anti-government or because they criticised specific individuals.

But people kept writing more. Unlike 1988, in 2014, the Indian media (and the general public) has several options open to voice opposition to any form of censorship, the Internet being the prime platform. If it does not manage to do so, it will be as much a failure of journalism, as it will be a reflection of Modi’s desire to dominate.

In a recent interview to ANI editor and mid-day columnist Smita Prakash, Modi went on record to say that the media’s primary role in a democracy is ‘criticism’. This is important, because, if he becomes prime minister and indeed attempts to stifle opinion, journalists need to hold a mirror to him and ensure accountability.

Hand-wringing and complaining just won’t work. If the media cedes its independence, it will have no else to blame but itself, and in the process will damage not only the institution of the Press, but also weaken other democratic institutions.

Sachin Kalbag is editor, mid-day. He tweets at @SachinKalbag. He can be reached at sachin@mid-day.com

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!