Mumbai non-profit helmed by Magsaysay winner helps unite missing man with family in Bhutan 13 years after he was presumed dead and gone

Social workers Samar Basak and Nikhilesh Sangad flank Phuntsho Wangdi and his father Namgay at the India Bhutan international border office

Tshewang Dorji alias Phuntsho Wangdi, 39, has been presumed dead by the local administration of his village in Thimpu, Bhutan, since December 2011. According to the law of the land, a person is presumed dead if gone missing for 12 years or more. His name was dropped from the voters list and the family’s ration card.

In a strange twist to the tale, Wangdi was repatriated back to his home country thanks to the efforts of Shraddha Rehabilitation Foundation which works for the welfare of mental health patients and is run by Magsaysay Award winning psychiatrist Dr Bharat Vatwani. This is the first repatriation of a mental health patient of Bhutanese nationality from India.

Not less than ‘God’ for us

“We all are very happy that our son is back home. The doctor is no less than ‘god’ for us. We are poor; we couldn’t offer anything to the doctor to express our gratitude, other than prayers and blessings,” Namgay Wangdi, 72, his father, told Mid-day on a call from Thimpu. According to him, his son, who quit school after class five, would help him run a bakery.

He is believed to have developed a mental health disorder as an adult when according to some reports he experienced a failed love affair. At the end of the year 2011, Wangdi left home suddenly. The Royal Bhutan police had in the past raised a false alarm. “So, when we received a call about his whereabouts this time, we weren’t sure whether to believe it or not.” On reaching the immigration office close to the India-Bhutan border, a few men and immigration officials were waiting for the family with Wangdi.

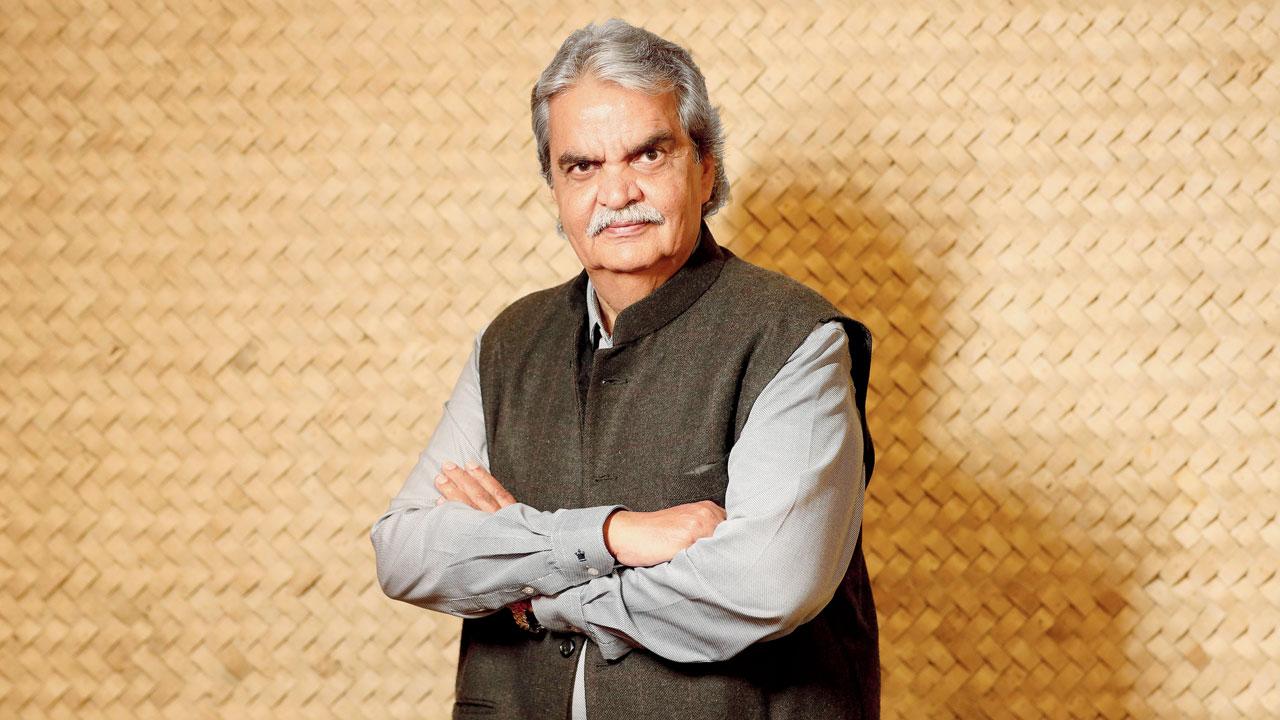

Dr Vatwani

Samar Basak and Nikhilesh Sangad, social workers attached to the Mumbai-based non-profit, who accompanied Wangdi to Bhutan, faced a challenge because the man had no legal documents to prove that he was a citizen of Bhutan. “It was only after we convinced the senior Border Security Force (BSF) officials at the international border, who spoke to their Bhutanese counterparts, the police and immigration officers, that they were able to track the family which had moved to Thimpu from an earlier location that Wangdi remembered. Tracing a family in a population of 8 lakh would have been tough, especially in the absence of documents to prove his nationality,” the social workers told this writer.

Where was Phuntsho?

Wangdi was handed over to the Shraddha Rehabilitation by the government-run Institute of Mental Health (IMH) in Chennai on June 25, 2023. He was at IMH since January 27, 2023 and was identified as Fayaz, a name that he had given at the time of admission. He was diagnosed with possible Schizoaffective disorder. Persons with the disorder could experience depression and psychosis. Schizoaffective disorder treatment can include therapy and medication. Under the care of Dr Vatwani at the NGO’s Karjat centre, Wangdi showed an improvement and began to gradually reveal little details about his past.

Basak told mid-day that during a counselling session, Wangdi had said that he used to help his father in baking bread, and was always keen to visit India. “He would also have arguments with his father and brothers. In December 2011, he left, without informing anybody.”

Wangdi is said to have done odd jobs in hotels near the India-Bhutan border and crossed over illegally sometime between 2011 and 2012. He then worked in hotels in Assam, moved to Meghalaya, then Darjeeling, before he boarded a train to Chennai in 2013 and worked in a hotel there. It was during the COVID-19 lockdown that he lost his job and was roaming the streets of Chennai before he was sent to IMH by a social worker group. Chennai posed for Wangdi the problem of language, Basak said.

“Humans seek emotionality and subconscious security which we receive in our homes, with our families, friends, through community, culture and food preferences. International boundaries should not prevent us from allowing someone this emotional cocoon,” Dr Vatwani told mid-day.

Dec 2011

The year Phuntsho Wangdi left his home in Thimpu

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!