Dahanu-based Warli artist, Rajesh Chaitya Vangad's work is finding increasing resonance in Mumbai. His recent assignment lends a healing touch to Tata Memorial Hospital

Warli artist Rajesh Chaitya Vangad's recent painting assignment demanded a four-hour commute to the Parel campus of Mumbai's Tata Memorial Hospital. For over two months, Vangad negotiated this distance of 145 kilometres from Ganjad, his village in Dahanu taluka.

Warli artist Rajesh Chaitya Vangad's recent painting assignment demanded a four-hour commute to the Parel campus of Mumbai's Tata Memorial Hospital. For over two months, Vangad negotiated this distance of 145 kilometres from Ganjad, his village in Dahanu taluka.

ADVERTISEMENT

The brief given to him was to sketch a tableau of India's iconic tourist spots, keeping in mind the hospital's cancer patients who hail from distant geographical zones of the country. Bright images on a red ochre background that exude positivity!

Vangad followed the brief and drew a collage of images , Amritsar's Golden Temple, Kolkata's Howrah Bridge, the Himalayan range that connote national unity and hope.

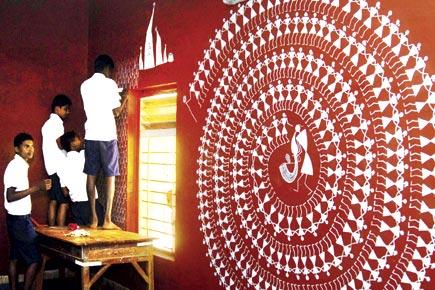

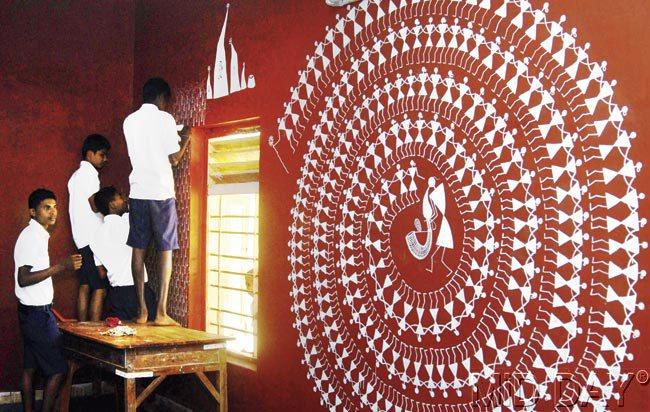

Students work on Warli painting by artist Rajesh Chaitya Vangad as part of Wall Art in Dahanu

Having finished the stint, Vangad was back to life in Ganjad, working on other wider canvases, which ask for his concentration on other thematic terrains. He will be unreachable on phone until he finishes eight major wall paintings commissioned by expatriate officials working in the Consulate of Switzerland in Mumbai.

A panel of Warli art done by Vangad at Tata Memorial Hospital

For a 40-year-old self-schooled (eighth standard passed) Warli artist operating from remote Ganjad, the diversity in Rajesh Chaitya Vangad's assignments is amazing. His paintings adorn the walls of Mumbai's new international airport terminal. His art displays greet you in the National Crafts Museum, New Delhi.

Warli painting demonstration

In June, later this year, he will hold a children's art workshop at Chennai as part of a SPIC MACAY convention on Indian cultural heritage. He is doing illustrations for a storybook on Warlis for the Delhi-based Katha publishing house. He is working on a residency project for foreign artists who wish to stay with him and witness his creative process.

Warli artist Rajesh Chaitya Vangad poses in front of his work at the Homi Bhabha block, Tata Memorial hospital, Parel. Pics/Shadab Khan

He is also gearing up for the Wall Art Festival in which Japanese artists are coming to his village to paint one of Ganjad's ashram schools. Another project on the restoration of the traditional Warli habitat currently occupies his mind space.

Beyond the CV

Rajesh Vangad's professional forays are appealing; each steeped in a specific social milieu, each calling for a buzzing cultural connection - none of which is contained in his one-pager bio-data. His blog post or his online profile does not reveal an iota of excitement that his art has generated over the last decade. In the context of today's media environment, Vangad is an interviewer's challenge.

His monosyllabic soft-spoken replies do not provide clues to his multi-hued career. It is after repeated efforts of unravelling that one gets an idea of the expanse of Vangad's porous art. Very often he is not articulate about the international groups that hosted him in the past. He doesn't recall the names of the ministers and past presidents who honoured him in the Festivals of India.

He takes recourse to a small diary which pins down the dates of his upcoming travel to France. It becomes the interviewer's task to piece together a trajectory that is not just 'happening' in the popular sense of the term, but is inspiring in the context of the bridges he has built, despite being a man of few words. The exchanges that his paintings have promoted, underline the potential for dialogue in the traditional arts.

For instance, he has regularly painted the walls of the Zilla Parishad schools in Dahanu, so as to attract drop-outs into the academic mainstream. Similarly, he has taken art classes for Japanese students last year. He spent time in the Niranjana School in Sujata Village (Bodh Gaya), using the walls of the school building as canvas. The idea was to electrify students' imagination and tell them about the importance of education.

The Wall Art Festival, of which he is now a permanent part, travels to schools which are facing a decline in class strength. "I loved that concept because I am myself a drop-out. I know what it is to bunk school and each student has different reasons for dropping out. Children wake up much later in life and realise how precious were those years," he opens up while talking about his incomplete schooling.

He says the school space should be lit up with attractive wall paintings, so that children don't run away from school. Warlis and other tribal communities of India suffer due to poor schooling and Vangad feels that paintings on school walls can play a positive role in formative education. He says a painting, of whatever style, is a welcome signal to the child. "A bright school structure makes a big difference to a person's life.

When people recall their childhood, they invariably remember their school buildings. I am hopeful that all Ganjad schools will shine with bright paintings in the days to come, so that the next generation of Warli students attends classes every day."

Painting and life

Vangad was born (June 1975) in a below-subsistence Warli household in Ganjad. Rice farming on over 14 acres of land was their sole source of sustenance. Vangad's father, (with two acres to the credit of his nuclear unit), took to carpentry as a side business, while his mother did traditional painting for festive occasions and weddings. Neither Vangad nor his four siblings ever thought of going to Mumbai in search of a job. They did not want to try their luck in a competitive city culture.

Instead, they decided to stick to Ganjad where a piece of earth could bind them as a family. As Rajesh Vangad dropped out of the school after the eighth standard, he found himself more interested in his mother's pictorial language. He felt close to the central motifs in each ritual painting - particularly the square known as the chowk. He could identify with the mother goddess and other scenes of hunting, fishing, farming, festivals and trees.

With very little else to do and no language skills to fall back on, he felt the ritual painting (dating back to 3000 BCE) done inside his hut could save him from dismal unemployment. "I felt that painting was my livelihood. As the family struggled to find its footing, I felt closer and closer to the earth and cow dung that made our walls.

The material used for painting - a mixture of rice paste and water, along with the bamboo stick used for paintbrushes - all of it seemed doable occupation for me," he reminisces the times when he started with odd jobs. He says the past seems like a distant canvas when he gives painting lessons to his two sons (now studying in the same school where he dropped out).

It is interesting that today Vangad, his educated wife and their sons look at painting as a creative profession. It was once a source of basic livelihood for him. After a Pune-based tribal art training institute recognised Vagad's work, he started looking at it in professional terms. He took minor painting work for companies in and around Dahanu.

Among his earlier assignments were Warli frames done for Bollywood stars, of which one was for director Subhash Ghai. As Vangad's reputation spread, he was approached by the National Handicrafts and Handlooms Museum. Thereafter he was entrenched in the various Festivals of India and craft melas where he drew Warli lifestyles on cloth, paper and walls. He is now an active contributor in the Dastakari Haat Samiti, the national organisation of artisans.

Connections galore

For an artist who started with limited means and who currently lives in an infrastructure-deficient semi-urban locale, Vangad has truly made many vital connections which Mumbai artists from more privileged backgrounds have been unable to achieve. He could have easily indulged in a conventional miscellany of sellable Warli paintings.

But his calling is visibly different. His involvement in creative projects makes him more than a painter. He is more of a creative collaborator who looks forward to placing his painting as part of citizens' initiatives, awareness drives and sensitisation workshops.

For instance, his paintings at the exhibition "Bapu: The Craftspersons' Vision" was the genesis for a Gandhi picture book for Tulika publishers. Tulika's My Gandhi Story rests on Vangad's impressions of Gandhiji - a historical figure he never met but came to know of through his school teacher.

Vangad revisited his history lessons and asked his teacher to recount the highlights of the Mahatma's life. Working with co-authors Nina Sabnani and Ankit Chadha, he then pieced together a Gandhiji who "was like us." What is most appealing in the book is the fact that the Father of the Nation has been portrayed as a simple villager drawing water from the well, wearing khadi, talking about peace and brotherhood. Vangad's Gandhiji is an approachable community leader, much like the creator of the book.

Like the Gandhi book, Vangad is also involved in another project celebrating the 15th century mystic poet Kabir. "I feel that Warli art should have these inspiring figures, images that we were not exposed to at one point. Mahatma Gandhi uplifted the poor people. He gave hope to people like me. Kabir spoke of a world without caste divides. I feel close to these people and want them in my art," he says.

In Vangad's paintings, the process of invoking the past becomes a task in itself. When he collaborated with the Japanese artists at the Sakura Wall art festival (Hozumisho school last October), he drew a luscious green rice field, a picture common to Sakura and Ganjad villages.

That was his way of drawing attention to a lesser known facet of India-Japan relationship - the friendship of Indian poet-philosopher Rabindranath Tagore and Japanese painter Arai Kampo. Vangad feels paintings become richer when prefaced with a prologue. Before going to Japan, he had therefore read about Tagore's association with Arai Kampo, particularly Arai's stay at the Santiniketan around 1916.

Art includes all

Vangad's secular open-ended view of Warli art is refreshing. He feels an indigenous art remains traditional and pure, even as new motifs enter the pictorial vocabulary. His predecessors, like the famous Warli artist Jivya Soma Mashe, have experimented with contemporary images, thereby extending the traditional ritual of painting to an artistic pursuit.

Vangad endorses the expansion of the art form and goes to the extent of stating that "art thrives when it expands." He feels there is a quintessential innocence in the Warli depiction of human and animal bodies, particularly the pairing of two triangles (the upper triangle depicts the trunk; the lower connotes the pelvis, both joined at the tip).

The Warli art has been appreciated for the unique equilibrium in the animated body shapes. Its popular appeal also stems from the fact that these paintings catch the rhythm of nature. Vangad feels that as long as the trademark innocence in the depiction is retained, the Warli artist is free to include new motifs and modern images. Many of his celebrated frames have delineated modern buildings, aeroplanes, cars and other consumer accessories.

"The entry of these motifs doesn't make the art any less traditional or less interesting. A painting is like a story on canvas. As long as the storyteller is open to influences, the painting will sparkle and burst with energy," that's how he puts across his idea of Warli art. As of now, his mind is divided between many projects.

But one day, when he is relatively relaxed, he intends to do more offbeat work which will infuse his paintings with unconventional images. He wants to paint a huge fresco on Lord Shiva's tandav; another one on the origin of the Earth; yet another on the effects of human pollution on bio-diversity; one more on Hindu gods and goddesses juxtaposed in a frame. The wish list is long, but mapped and timed for future delivery. It is definitely worth the wait.

The writer is a Mumbai-based cultural chronicler.

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!