A new campaign hopes to bring respect to street musicians with jamming sessions inside city’s trains

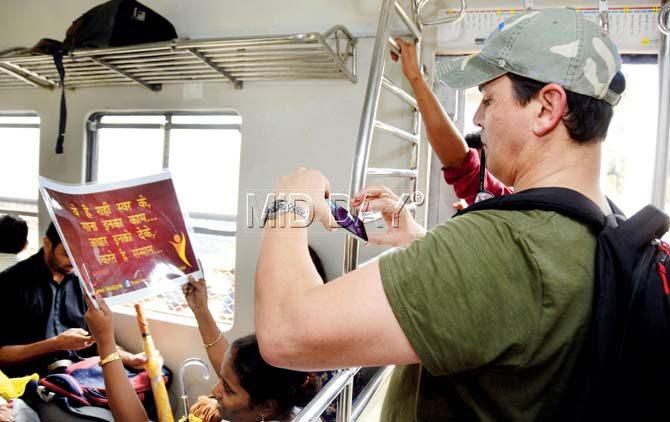

Street artistes Vilas Lone (left) and Chetan Patil entertain commuters with their music performance on a local train on Friday afternoon. Pics/Sneha Kharabe

ADVERTISEMENT

Dholak player Chetan Patil is familiar with singing in Mumbai’s local trains. After all, he has done it for more than ten years. However, unlike earlier, when he would pace the length and breadth of the compartment begging for alms, this time he takes a seat. Accompanied by Vilas Lone, a visually challenged musician and a few members of NGO Swaradhar, Patil begins singing Marathi composer duo Ajay-Atul’s chartbuster Deva Tujha Dari in his folksy voice.

Before we know it, the compartment has transformed into an ad hoc sit-down concert. Curious commuters, who earlier paid no heed, now crane their neck to watch the performance, while others take videos and tap their feet. One of the commuters even slips a Rs 100 note in Patil’s hand.

A local jam

Welcome to a session of Dabbajam, a recently launched campaign by Andheri-based NGO, Swaradhar. Founded by 25-year-old Hemlata Tiwari, the NGO aims to provide a dignified platform to talented street artistes. The campaign was started due to the lack of a culture for street performers. “Unlike UK and Europe, in India when artistes sing in local trains, they are labelled as beggars. We want to change this perception, and help them get the respect they deserve,” says Tiwari.

To drive the point home, documentary filmmaker and member, Deep Kakade, has been roped in to play narrator during the jamming sessions. “They might not be the best singers, but they are making an effort to use their talent to earn a livelihood. I introduce the players, talk about why we are here and exhort people to treat them as artistes and not beggars,” says Kakade, who till now has been part of four jamming sessions.

The sessions are held every alternate Saturday. “We understand that for many Mumbaikars, the only me-time they get is during a train ride. We don’t want to disturb that brief interlude of peace and introspection,” says Tiwari.

The team normally organises the session in the afternoon when the trains aren’t crowded. “We change compartments or get off at a particular station and board another train in order to reach a wider audience on a given day,” she tells us. The songs are chosen on the basis of popularity and are usually in Marathi or Hindi. “But, we make sure it’s a peppy number so that people don’t get bored,” Tiwari adds.

A struggle for livelihood

Interestingly, all the 25 singers on board are educated. While Lone has a Sangeet Visharad degree (Bachelor of Music), Patil has completed his HSC. “Sadly, because most of them are physically challenged, they could not get jobs,” says Snehal Adsule, a member of the NGO.

It took two years of research for the team to identify artistes and convince them to join Swaradhar.

“We have travelled in trains on both Central and Western lines, but it wasn’t easy to get them on board,” she says. The NGO also collaborated with PUKAR, an independent research collective, to ascertain the reason why people choose to sing in trains.

Among the artistes, only five per cent are from Mumbai, the rest are migrants from Rajasthan and Gujarat. “For some, performing in trains has been a family tradition, and for others, it’s a matter of sheer necessity in the absence of other opportunities,” says Adsule.

Patil, who used to run a PCO booth in the past, before selling wares and singing in trains, admits he was apprehensive when he was approached for the project. “I have been conned by people who promised to help me in the past. So, initially, I found it difficult to trust them. But once we started work, I realised they were genuine,” says Patil, who was invited by a TV channel to feature on a music reality show with Amitabh Bachchan last year.

A license to act

The first session of dabbajam was held two months ago from Thane to CST and back. The response, Tiwari tells us, has been overwhelming with many commuters coming forward to sing along.

The problem, however, is the absence of law in support of such streets performances. “Unfortunately, people who sing in trains fall under the purview of the Anti-Begging Act that bans singing, dancing or fortune telling in local trains for the sake of livelihood. They often face harassment from train authorities,” says Tiwari.

The team is now trying to work on a petition to obtain permission to acquire licence for such performances. “We are studying the laws and plan to collaborate with TISS to work a way around this problem,” she says.

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!