Valsad's mango farmers say they are happy to give land, but only if the govt plays fair

Harshadbhai Patel next to the cement block that marks his land. Pics/ Sneha Kharabe

Valsad: Harshadbhai Patel, a local farmer in Jujwa, Valsad, calls the government audacious. The 60-year-old who grows mango, chikoo and sugarcane and owns two acres and 14 gunthas of land, both non-agricultural and agricultural, in a prime area, says the authorities are offering him just R28 lakh for 20 gunthas [half acre] that could otherwise fetch him at least R2 crore.

Valsad: Harshadbhai Patel, a local farmer in Jujwa, Valsad, calls the government audacious. The 60-year-old who grows mango, chikoo and sugarcane and owns two acres and 14 gunthas of land, both non-agricultural and agricultural, in a prime area, says the authorities are offering him just R28 lakh for 20 gunthas [half acre] that could otherwise fetch him at least R2 crore.

ADVERTISEMENT

Harshadbhai takes us to his non-agricultural land, which he earlier intended to transform into a commercial business centre. As we walk through his land in Jujwa, he says, "This land falls in the commercial area of Jujwa, so the market value is very high. When I found out that this part is going for the bullet train, I asked about compensation. I wanted to use the land to build a shopping centre, with which I would rake in crores in profit. They offered just Rs 28 lakh."

This is in stark contrast to the plan laid out in Japan International Cooperation Agency's (JICA) Resettlement Action Plan. JICA is partly funding the project. Among the several guidelines, it was said that affected people would get fair compensation i.e. market price for their land and property. That's certainly not the case in either Valsad or Dungra village in Vapi.

Tanoj Kumar, an adivasi from Dungra, says, "Our home was built by our ancestors. Where will our family of 12 go if the government forces us to vacate?" His home stands on an area of 10,000 sq ft. "We should get Rs 50 lakh at least, but they are saying they will give us Rs 3 lakh. How have they decided these rates?"

The mohallas of Vaghaldhara village that will be razed

The mohallas of Vaghaldhara village that will be razed

A local activist tells us that, in 2007, Dungra village was registered under urban limits. But the jantri (land) rates were not revised. "Once a village comes into urban limits from rural, the market rates need to be changed. While per sq foot, the market rate is R400, people here are promised only Rs 176. So, one acre land will be bought for Rs 7,40,000, but ideally the rate is Rs 1,60,00,000," he informs.

Wiping out entire farms

The road to Gundlav village, 7 km from Valsad city, is lined with mango trees. Bhagubhai Patel catches our glance and adds, "Some people want to destroy this landscape. Can you imagine wiping out these farms and trees?"

Bhagubhai, 67, is the president of the Gujarat Khedut Samaj's (GKS) Valsad chapter. Until a few years ago, he was the manager of the Valsad District Cooperative Bank, and would often visit Mumbai for bank-related work. "I used to take the Shatabdi Express and reach Mumbai in three hours. The trains were mostly empty then, and more so today. Why then do we need a high-speed rail corridor between these cities?" he asks.

Bhagubhai says he actively started working with the GKS about three years ago, when the bullet train was announced. "They published a notification in a local newspaper on February 1, 2017, stating in Gujarati the number of villages that were to be affected by the bullet train," he says, adding, "Those who could read, saw what the future held for them. But the illiterate didn't know that the authorities were going to bulldoze through their farmland."

Bhagubhai Patel, Harshadbhai Patel, Navinbhai Patel and Jinabhai Patel

Bhagubhai Patel, Harshadbhai Patel, Navinbhai Patel and Jinabhai Patel

According to the notification, 30 villages in Valsad district will be affected. "Valsad is known as the mango capital of Gujarat. It has also been declared the Agri Export Zone by the Agricultural and Processed Food Products Export Development Authority and has since prospered because of its high-quality mangoes and chikoos. Farmers with small land holdings depend almost entirely on fruit production for their income," Bhagubhai says. Agri Export Zones were introduced in 2001 as an agricultural equivalent of Special Economic Zones, so that state governments could invest in resources to help boost production and export of crops conducive to that region.

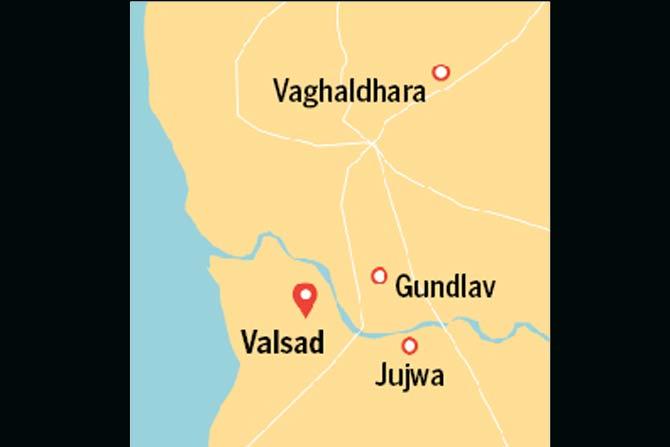

Gundlav, Vaghaldhara and Jujwa villages. Map/ Uday Mohite

Gundlav, Vaghaldhara and Jujwa villages. Map/ Uday Mohite

In Valsad, villagers are largely dependent on their agricultural land. "Through these notifications, the government should declare what the market value of this land is, but they don't. The market value for one bigha (70 per cent of one acre) is nearly Rs 70 lakh. But, farmers are being offered a maximum of R40 lakh. The villagers are not against development, but they deserve fair compensation," he says.

Harshadbhai says that about a year ago, NHSRCL officials visited Jujwa and handed receipts stating how much money each landowner would receive. "But they had no official signature nor were these on a letterhead. They were not authentic; merely pieces of paper with a random amount written on them," he says. Harshadbhai also runs a cement company and earns about Rs 3 lakh to Rs 4 lakh annually. "Our panchayat has not given permission for this project, but the officials are telling me they will transfer the compensation amount directly into my account."

No need for consent

The government no longer needs a landowner's consent to take away the land for a public project. In August 2016, President Pranab Mukherjee gave his approval for the Right to Fair Compensation and Transparency in Land Acquisition, Rehabilitation and Resettlement (Gujarat Amendment) Bill 2016 passed by the Gujarat Assembly in March that year. "Among other things, a key amendment in the Bill removed the provision of seeking the consent of the affected parties. While the original Act required 80 per cent of landowners to approve the acquisition of their land, this Bill states those provisions need not be followed if the land is being acquired for public purposes," Bhagubhai tells us.

In Valsad, Bhagubhai says, about 800 to 1,000 farmers will be affected by the project.

The Resettlement Action Plan, drafted for JICA by Arcadis and available on their site, states that those who lose their lands should also be "compensated for loss of properties (land, structure, and others) of individual as well as that of the community and loss of livelihood; to provide better living conditions and making concerted effort for providing sustainable income to affected families and lastly, to develop a harmonious relationship between acquiring body and affected families."

But, that doesn't seem to be the case in Valsad at least.

Navinbhai Patel, a scheduled tribe farmer, takes us to Vaghaldhara, a hamlet 20 km from Valsad. In this tribal village, residents live in separate mohallas. Each mohalla has around seven homes. In Navinbhai's mohalla, we enter his newly built two-storeyed pucca home. "In our mohalla, all seven homes are going to be demolished. I am losing 500 mango trees and 20 to 25 chikoo trees. When the bullet train officials arrived here a year ago, they gave us a receipt which said I would be paid R24 lakh for my land. But the market value is almost double that, so I refused the offer," the 55-year-old tells us.

His uncle, Jinabhai Patel, who lives in the same mohalla, is losing both, his land and home. The 70-year-old farmer says, "They threatened to destroy everything and not give us a penny if we didn't give consent. We are scared, but will not budge. I live with my wife, sons, their wives and kids here. Where will I go?"

Jinabhai even suggested that they be given land elsewhere instead. "But they are not agreeing. There are no promises of resettling us either. This project will affect Valsad's mango production. The district will lose its essence," he adds.

'Idiotic project'

The route will also pass through coastal regulation zone (CRZ) areas of Palghar and Dahanu. Brian Lobo (in pic) of the Kashtakari Sanghatana, a movement advocating the rights of tribals, says, "Three years ago, when we found out about the bullet train we thought, what do we do now—the project is idiotic. In a country where means of transport are slow with fewer basic facilities and lack of safety, they want to run a train that will serve only 508 km. It should feature nowhere on the country's priority list for development." Lobo thinks development priorities should focus on bettering the existing railway system. "Also, why just have a certain section of society benefitted by this project, when there are alternatives to serve the entire country?"

Mumbai takes a hit

The bullet train project is set to fragment the Sanjay Gandhi National Park, the Tungareshwar Wildlife Sanctuary and the Thane Creek Flamingo Sanctuary. In January, at the 52nd meeting of the National Board for Wildlife, chaired by Union environment minister Dr Harsh Vardhan, wildlife clearance was given to the Mumbai-Ahmedabad high speed train corridor. The minutes of this meeting, a copy of which is with mid-day, has revealed that the board has laid pre-conditions for the project. The board said two wildlife corridors will have to be built for animals. The first corridor will be an overpass over the existing Diva-Vasai railway line, and the proposed rail line for the bullet train. Space for the second corridor will be made by elevating the existing 1.5-km Chinchoti Anjur Phata road.

The board said MMRDA shall be responsible for the design and construction of the elevated road section.

Catch up on all the latest Mumbai news, crime news, current affairs, and also a complete guide on Mumbai from food to things to do and events across the city here. Also download the new mid-day Android and iOS apps to get latest updates

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!