An upcoming exhibition by one of Mumbai’s earliest fashion designers and a film screening about the forgotten art of block printing retrace the city’s tryst with textiles

A hand-carved block and the printed fabric

Let's rewind to the 1970s; a new era that would firmly affix Mumbai’s status as the nation’s fashion capital. The city’s fashionistas awoke to Bombay’s (as it was known then) first-ever ‘designer’ exhibition. On offer were block-printed cotton salwar kameez sets (today’s co-ords) and sarees by Mita Parekh, a city-based textile artist who would go on to dress some of the era’s most sought-after names. Parekh’s design lens was unlike the maximalist aesthetic that had begun seeping into traditional Indian wear from Delhi-based designers. Her use of block prints, soft pastel tones, and minimalist but sharply contemporary motifs and colour combinations, struck a chord immediately.

ADVERTISEMENT

Parekh's prints on a saree from an exhibition held in the 1980s

Soon, the city’s youth were trading in their trousers and skirts for sleek salwar-kameez sets, proud to showcase their modern Indian identity with a design ethos that resonated with the Western fascination for all things bohemian. In fact, Parekh reveals that her then 20-something-year-old daughter Radhi (now a SoBo gallerist) would proudly wear her mother’s creations to the discotheque, echoing her mother’s rebellious nature!

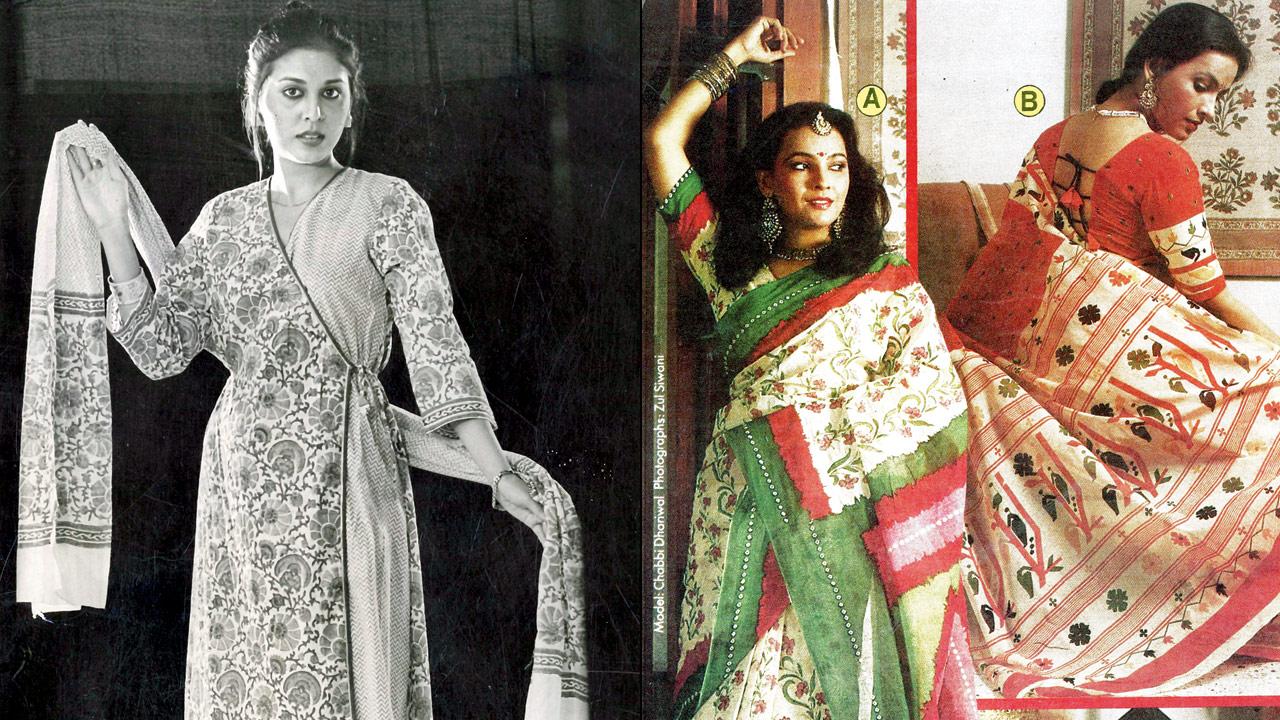

Block printed salwar kameez. Pic Courtesy/Jitendra Arya (right) A panel from an advertising campaign from the 1980s

Parekh's idea is poised to make a stylish comeback, with an all-new colour palette and a new medium, silk. This time around, she has traded in her blocks with discharge printing to create more vibrant designs. The upcoming exhibition will feature a collection of limited-edition sarees, dupattas and stoles that bear the markings of Parekh's unabashed love for all things artisanal and hand-made, and also reflect a marked shift in her design aesthetic.

Same, but different

Having studied design at Drexel University in Philadelphia in the late 1950s, Parekh delved deeply into mid-century Modernism, visiting leading designers at the height of the movement. She studied the Philadelphia Museum of Art’s collection of paisley shawls, for her MFA thesis. Her studies informed her design aesthetic, as did her Gandhian roots, which led her to astutely understand that handmade textiles and garments had to be made accessible at affordable price points to make their way into middle-class wardrobes. Unsurprisingly, her maiden collection sold out almost immediately. At the same time, Parekh was exporting block printed cottons to the West, which was in the throes of the Hippie Movement.

Mita Parekh

When we quiz her about whether fashion has come full circle, with fashion forward folk waking up to the importance of preserving these indigenous crafts, she explains, “Younger generations are resonating with the values that underpinned the counterculture movement of the 1970s — many of the ideals then, including sustainability and environmental consciousness are talking points for today’s youth. So, we have seen an encouraging trend of them choosing handmade over fast fashion. It is heartening. While it may be impossible to eradicate fast fashion completely, there is a need to create more demand for handmade garments to help democratise Mumbai’s consumption patterns.”

Conscious revival

The Indian government’s clarion call for ‘Vocal for Local’ has seen many brands create their versions of reviving Indian crafts. Mother and daughter, however, feel the need to detach the nationalistic sentiment that has been surrounding such revivals. “In the 1920s, there was a mass movement towards khadi with the Quit India movement. In the '70s, young Indians were reclaiming their roots with traditional Indian motifs. This time, however, we must think of ‘handmade’ objectively. We must all mindfully push towards bringing back the authentic,” they say.

An example of the block print from the film

Parekh’s roster ranged from actor Nargis to former Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, and included past beauty pageant winners. Parekh is clear that the country’s tastemakers, including actors and even political figures, can serve as fashion role models. Their endorsement of Indian crafts will encourage coming generations to embrace indigenous crafts and handmade textiles, she concludes.

ON October 3, 5.30 pm (exhibition preview); 6 pm (film screening and discussion open to all)

October 4 to October 6; (exhibition and film screening on all days)

AT ARTISANS’ Gallery, 52-56 VB Gandhi Marg, Kala Ghoda.

CALL 9324732348 (RSVP mandatory for film screening and discussions on opening day)

Also Read: Bell-bottoms to ballet flats: The glorious revival of vintage fashion trends

Block-printing the city's textile heritage

In 2009, Mala Sinha, founder of Baroda-based Bodhi, a sustainable studio focusing on block prints, purchased 7,500 blocks from a Mumbai-based karkhana (workshop) that had long ceased operations. “When the blocks arrived, I was dismayed to find how improperly they had been stored and transported. They had been thrown together in large gunny sacks, were covered in years of dirt; many had been irreparably damaged. While purchasing it, my intention was to incorporate these prints into my own products. But that was impossible,” Sinha recalls. Revisiting those blocks later, Sinha’s team attempted to salvage it, by gently cleaning them. As she reviewed them, she was surprised by its patterns and designs.

Filmmaker Mala Sinha with industrial designer Pradeep Sinha in a moment from the film

“They were diverse and unusual. Each region has its block printing traditions, which are steeped in heritage. However, this set of blocks highlighted to me something I’d often pondered before. In our design education, we’re accustomed to learning from the best — whether royal costumes or crafts that were patronised by the aristocrats and nobles. We don’t look at what is worn by the common people. We don’t think it is worth our while studying that. These blocks were basic and presented a sense of urgency, almost as if the cloth had been woven and it had to be printed that same evening.

There was no attempt to convert the block into a timeless heirloom. It also suggests that they were meant for what could be consumed immediately, which is also what Mumbai is all about. We are not here to revisit history. We move on quickly, changing with the times. It was fascinating to view these not from the lens of timelessness, but rather the flight of time,” Sinha elaborates. In her eyes, the blocks represented the true democratisation of the craft. Intrigued to learn more about its origins, Sinha arrived at these karkhanas in Mumbai.

Although many had shut down and countless artisans who had travelled to Mumbai during the textile boom had either passed away or returned to their villages due to fading demand, Sinha captured several conversations with those who remained. It is these conversations; snippets of Sinha’s journey of these blocks and their restoration that form the subject for The Modern in Print, a documentary that captures the once-prolific textile printing industry that Mumbai was home to.

The film’s narrative is based on first-hand research by Sinha and Suchitra Balasubrahmanyan, with Dinaz Kalwachwala directing the piece. Through the patterns created that range from a simplistic nautical print of sailboats and a charkha, to an extravagant recreation of a Mughal-e-Azam poster in five colours, the makers revisit the fascinations, ideals and dreams of erstwhile Mumbaikars, which have been frozen in time, on these small pieces of wood. The film also touches upon how commissioning personalised blocks and prints became a status symbol for the affluent and powerful in Mumbai, while the working classes eagerly embraced the quickly-made, cheaply-produced printed cotton textiles en-masse, grateful for the comfort, convenience and aesthetic that these garments afforded them.

The film draws attention to how the advent of technology and fast-fashion alternatives led to the demise of such workshops, Sinha adopts a pragmatic approach. “It is foolish to hold on to the romantic notion of preserving the ones that are located in some of Mumbai’s most prime real estate. It’s also elitist to demand that these artisans continue to toil in a largely-manual trade, without aspiring for upward mobility, so that our nostalgia can remain intact. However, we can hope for this era to be remembered, whether through a museum or a preserved heritage site,” she suggests as a viable solution.

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!