Vaseem Khan, author of Baby Ganesh Agency series and Malabar House crime novels, recently became the first non-white Chair of the UK Crime Writers’ Association in its 70-year history. The British author talks shop, and why Mumbai is the star in his plots

Vaseem Khan

His first book, The Unexpected Inheritance of Inspector Chopra, was a Times bestseller and has been translated into 15 languages. Vaseem Khan was born in Newham, but spent a decade in India, and his crime novels, the Baby Ganesh series and the Malabar House series are popular with Indian readers. Recently, he was conferred with the Chair of the UK Crime Writers’ Association (CWA), which is the oldest and largest association of crime writers in Europe. It exists to promote crime writing and crime writers. He elaborates on the expectations, “It is to chair the association for the next two years, following in the footsteps of world-famous crime writers like Ian Rankin and Dick Francis. As the first non-white writer in this role in its 70-year history, my main responsibility is to spread the gospel, to tell writers of all backgrounds and from all countries that crime writing is an open field. If you like murder — come and join in!”

Khan and his boss Terry Brewer in Mumbai in 2000

Edited excerpts from an email interview:

What gives you the most satisfaction while writing crime fiction?

Crime fiction allows us to examine the world around us — and to learn while being entertained. For instance, my Malabar House novels — which are set in 1950s, Bombay — are crime novels but they allow me to slip in details to correct omissions and misconceptions from the British rule in India. In The Lost Man of Bombay, the third in the series, a white man is found murdered in the Himalayan foothills with only a notebook in his pocket containing cryptic clues. In the book I mention that Mount Everest was named after a Welsh surveyor who worked in India. But George Everest never went near the mountain, nor determined that it was the world’s highest peak. An Indian named Radhanath Sikdar did that. Alas, you won’t find Sikdar’s name on any map. We often hear that history is written by the winners. It gives me great satisfaction to redress the balance.

How do you separate fact from fiction?

My novels are tightly plotted, with plenty of clues — I write in a Golden Age/Agatha Christie style — and I have a tried-and-tested method that works. I use a gentle note of humour too, a wry observation of the world around us. Everything I write about is based on real experiences; if not my own, then of other people’s. At the end of each of the Malabar House books, I share all the facts that the story was based on. My readers find it fascinating that so much that seems fantastical is actually based on real events.

How did Bombay/Mumbai become central to your novels?

While in my twenties, I lived in Bombay for a decade, and those incredible memories power my writing. My first series (Baby Ganesh Agency novels), starting with The Unexpected Inheritance of Inspector Chopra, is about a middle-aged policeman who retires and solves murders while having to look after a baby elephant. Those books are set in modern Mumbai. But my latest series, the Malabar House novels, are set in 1950s Bombay, and look at the foundation of the modern India we see today. That post-Independence era was a complicated time because places like Bombay were still highly cosmopolitan and India was re-negotiating her relationship with Britain. The latest book in this series, Death of a Lesser God, asks a simple question — can post-colonial societies treat their former colonisers justly? James Whitby is an Englishman born in India during the Raj, convicted in post-Independence India of murdering a prominent Indian lawyer. He claims that he is innocent, the victim of a form of ‘reverse racism’. My lead character, Persis, India’s first female police detective — working with Archie Blackfinch, an English forensic scientist in Bombay — has 11 days to find out if Whitby is innocent or guilty before he is hanged.

Is it a challenge to incorporate desi-themed plots while writing for an international audience?

My readers from around the world are fascinated with past and present India. The Malabar House series was born of my desire to explore India just after Independence. Beginning with Midnight at Malabar House, we witness a nation still reeling in the wake of Gandhi’s assassination and the horrors of Partition. Persis, determined to prove herself in a man’s world, is banished to Bombay’s smallest police station, Malabar House, populated by rejects and misfits. The murder of an English diplomat falls into her lap, and she must work with an English forensic scientist named Archie Blackfinch, deputed to Bombay from London’s Met Police. It’s an uncomfortable, will they-won’t-they relationship. How can an Indian woman in post-colonial India consider an Englishman as anything more than a colleague…?

Your favourite crime writers?

They range from classic authors such as Agatha Christie — her Poirot stories — to modern masters such as Michael Connelly and his brilliant Detective Harry Bosch novels set in Los Angeles, and Louise Penny’s atmospheric Inspector Gamache books set in small-town Canada. One of my favourite crime novels is The Name of the Rose by Umberto Eco, a philosophical, historical and mystery masterpiece.

Around the city with Vaseem

The crime writer reveals locations found in his books

Crawford market

>> Dharavi’s slums feature in an entire chapter in The Unexpected Inheritance of Inspector Chopra as Chopra investigates the murder of a poor boy.

Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Vastu Sangrahalaya. File Pic

>> In The Perplexing Theft of the Jewel in the Crown, we see a theft of a priceless artefact from the Prince of Wales Museum (Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Vastu Sangrahalaya).

>> In Bad Day at the Vulture Club, a wealthy Parsee is murdered and so we visit the Tower of Silence.

>> In the Malabar House series, the reader enters Asiatic Society of Bombay (from where a 600-year-old copy of Dante’s The Divine Comedy is stolen in The Dying Day).

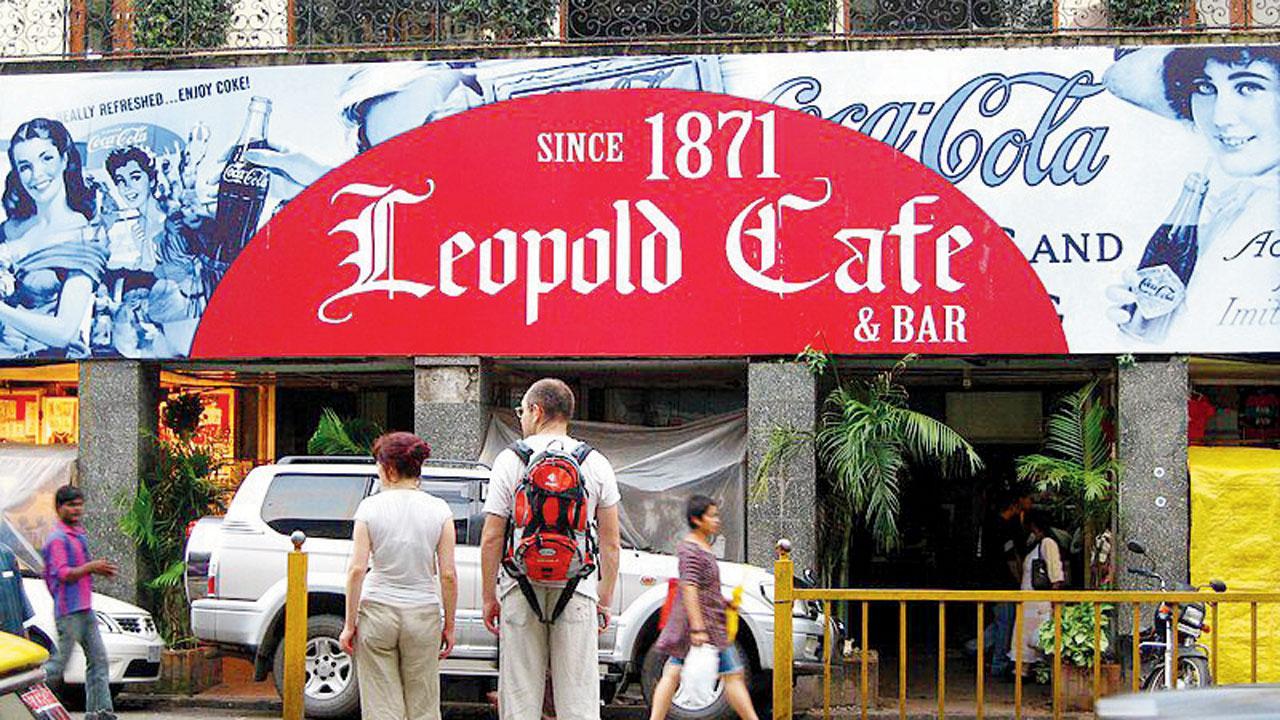

Leopold Cafe. Pics Courtesy/Wikimedia Commons

Leopold Cafe. Pics Courtesy/Wikimedia Commons

>> In The Lost Man of Bombay, Persis ventures into Crawford market, Leopold Café, Bombay University, Arthur Road Jail and the St Pius X College in Goregaon — after a Catholic priest is murdered.

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!