In the first biography of Charles Correa, one of modern India’s greatest architects, Mustansir Dalvi showcases not just his visionary genius but also his zeal to improve the lives of the common man, particularly in Mumbai

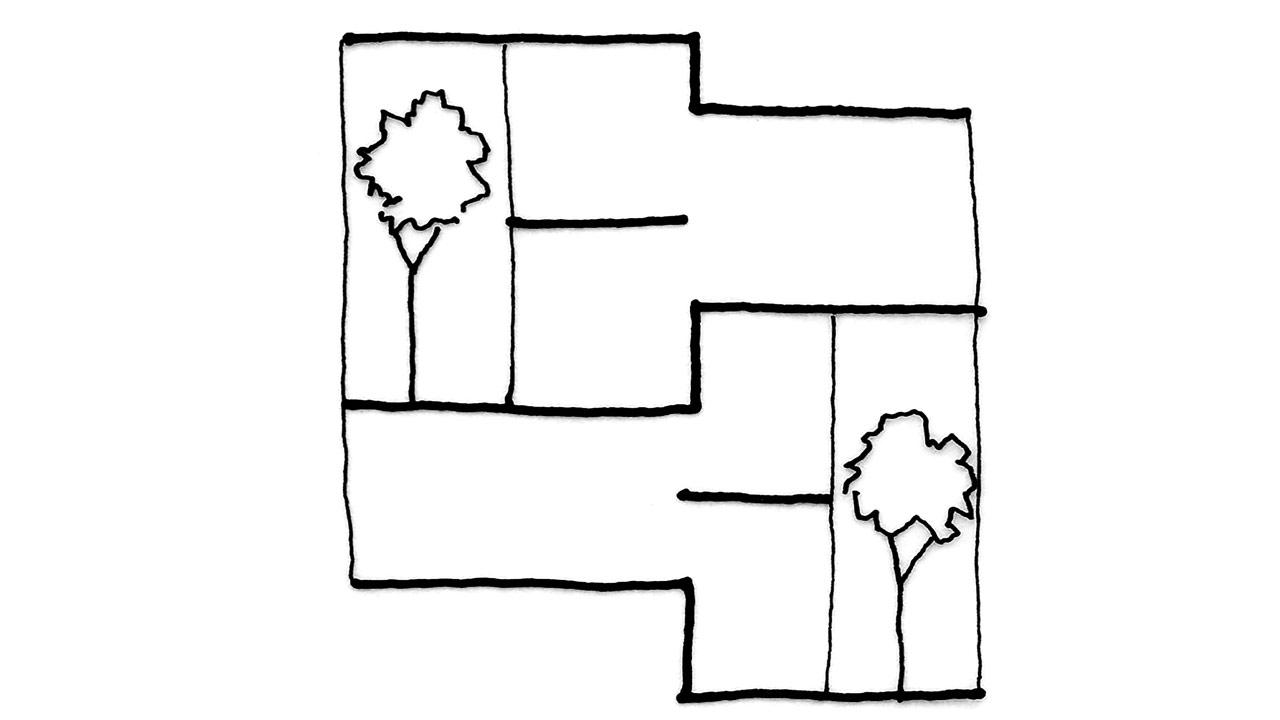

An illustration of Charles Correa. PIC COURTESY/DOULURI NARAYANA, NIYOGI BOOKS

The average Joe. Early in Mustansir Dalvi’s engaging biography of Charles Correa, the reader is introduced to Joe, the working township protagonist in You and Your Neighbourhood, an animated film the iconic architect directed as his final Masters’ thesis at MIT. We are given a peek into the then-aspiring architect’s vision, where he backs the power of individual acts and public participation for greater civic good. Dalvi was commissioned to write Citizen Charles (Niyogi Books) that releases today at Z Axis, a conference in Mumbai that honours six decades of Correa’s ideas. “I am glad that I got a chance to reconvene with his life, work and thoughts, as an architect and a true-blue Bombaywallah,” shares the architect, academic and author-poet. The title was chosen, Dalvi explains, because, “he epitomised an involved citizen. Correa’s architecture is an extension of this engagement.”

Kanchanjunga Apartments, Mumbai. FILE PIC

For the reader, it’s an insightful, well-paced chronicle about one of post-independent India’s most brilliant minds. The narrative is lucid and doesn’t overwhelm with technical or academic jargon. The handy size makes it less intimidating for readers who’d like to discover Correa’s legacy. The QR codes linked to his films are a bonus that open a window to his filmmaking avatar. Dalvi recalls the process of putting his life into words, “Piecing together a biography as a narrative was challenging. I was fortunate to be able to interview both Monika Correa, Charles’ wife and partner in the adventures that made such a rich life, and Nondita Correa Mehrotra, Charles’ daughter, for information about his family, background and younger days, and for their insights into his work and career. They were most generous.”

Layout of the building (1962): © Charles Correa Associates, courtesy Charles Correa Foundation

The early chapters offer a peek into his emerging dream. The Bombay connect began as a schoolboy who lived in Ballard Estate and studied in St Xavier’s Boys’ School in Dhobi Talao. Dalvi feels Ballard Estate could have played its part, “The Ballard Estate we see today is, physically at least, the Ballard Estate that Charles grew up in. This is a planned part, the work of George Wittet, who created a compact precinct that connected the docks with the main business areas of Bombay. Charles grew up seeing these stately piles, with their classical details. He must have walked down its tree-lined avenues and that this quiet sense of order and calmness, of a Bombay that once was, must have profoundly influenced his own space-making as an architect.”

Jawahar Kala Kendra in Jaipur. PIC COURTESY/ Wikimedia Commons

Mighty Joe

His interest in design and architecture took him to MIT School of Architecture and Planning. Dalvi recaps those years as only a fellow student of architecture would. “Correa was lucky to get enlightened teachers at MIT, broadminded enough to accept a twelve-and-a-half-minute-long animated film, called You and Your Neighbourhood, in lieu of a dissertation. His film, where Joe plays the neighbourhood hero, showed how homeowners in downtown Boston facing urban blight due to additions of infrastructure and urban sprawl, could improve their lot by making incremental changes to the spaces around them in collaboration with the police and health systems.” Correa believed that positive change was not dependent on top-down urban planning by professionals. His work was appreciated by his teachers and authorities in Boston. “The inferences from this film can be seen in Correa’s work through his career, whether in seeking solutions from local contexts or appreciating the value of design being built incrementally.”

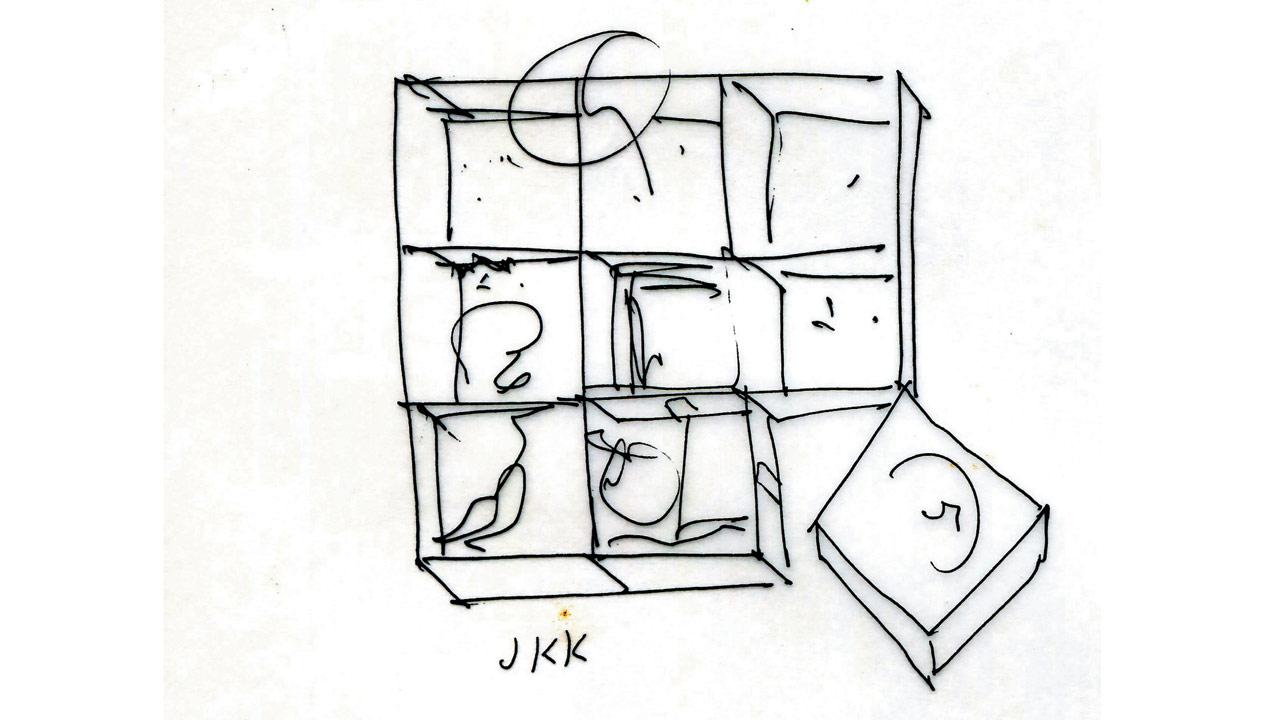

A rough sketch of its layout (1986): © Charles Correa Associates, courtesy Charles Correa Foundation

Climate matters

Correa, the visionary, described Indian architecture as “a three-legged stool: climate, technology and culture”. Dalvi explores in detail this maxim by citing multiple examples of his designs where these terms found a synthesis and harmony. “His ideas about climate were developed in his earliest mass-housing projects, including his prototypical Tube House and the PREVI housing in Peru, and his iconic Gandhi Smarak Sangrahalaya. Climate continued to be a central concern right into his later buildings like Lisbon’s Champalimaud Center for the Unknown.” With India already experiencing the effects of climate change, Dalvi has a message for young architects, “We will all have to tackle it sooner rather than later, and they would do well to follow Correa’s central tenet: ‘Form Follows Climate’.”

TLC for Bombay

“I realised, by the time I finished the book that to understand Correa best, you have to look beyond his architecture and to try to appreciate him as an active participant in the life of his city, his country and his world. His concerns were the people he built for. He explored the possibilities of the local, and his designs emerged from these granular understandings.”

Mustansir Dalvi

The book, apart from saluting Correa, offers insight into a period in post-independent India when leaders and administrators were in sync with Indian architects like Correa and his contemporaries, and even looked overseas (Le Corbusier - Chandigarh). With the New Bombay plan, while it was unfortunately never fully realised as Correa had envisioned it, interestingly, extensive coverage in The Times of India and a special edition of the MARG magazine in the 1970s, nudged civic authorities to consider it as a suitable remedy to decongest the island city where he suggested creating a ‘satellite city’ on the mainland, connected via a series of waterways.

In the concluding chapter, Dalvi writes: ‘It is a loss to the city as well as to the architect, that so little of his vision was realised here.’ He elaborates, “Correa’s frustrations and ours, as good citizens, are rooted in his unrealised public projects, urban interventions in Bombay that would have left the city a much better place, but for various vested interests and the hubris of the State.” Key plans like the Backbay Plaza, the eastern waterfront, Fort’s overhead pedestrian walk, and the pavement dwellers’ project, never took off; the truncated Mill Lands plan diluted his vision of bringing to the city a large consolidated public green common space. “Correa did a lot for the city. The city did not follow up,” Dalvi reminds us.

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!