Is non-submission of ‘literary’ books for top Indian book prizes the result of non-clarity in submission guidelines? Or is it publisher error, genuine oversight, and/or indifference? Preeti Singh attempts to read between the lines

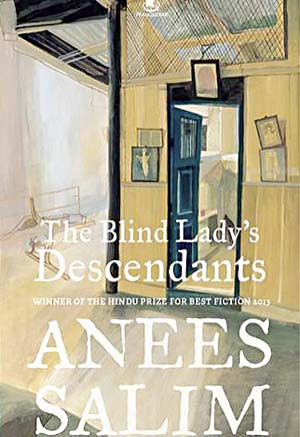

Anees Salim’s The Blind Lady’s Descendants won the Crossword Fiction Award this year; it engaged many readers with its Marquez-esque symbolism and themes, especially the inseparability of the past, present and future. Set in Salim’s hometown, Varkala in Kerala, the novel is an almost 300-page-long suicide note by young Amar.

Anees Salim, author

Blindness is pervasive in The Blind Lady’s Descendants the grandmother is blind and the figurative blindness of her descendants sets them on a path of destruction. Ironic then, that this blindness also extended to the Crossword Awards, where The Blind Lady’s Descendants did not make it to the initial longlist.

Not only were some big publishers left out of the mailing list, but the jury member, Anjum Hasan, also realised that publishers had overlooked notable titles on their lists. Hasan says, “Salim’s was among several worthy fiction works not submitted, including Amit Chaudhuri’s Odysseus Abroad, Kaveri Nambisan’s A Town Like Ours and Altaf Tyrewala’s Engglishhh.”

According to Jai Arjun Singh, another juror, “a lot of space on the longlist was an over-generous sprinkling of barely written, not-at-all-edited books by Srishti, Leadstart and other publishers who operate in a grey zone on the outskirts of self-publishing.”

Anjum Hasan and Jai Arjun Singh

The title saw the light of day after Hasan made a list of titles (including Salim’s book) and asked Crossword to have those sent across as well. The judges had been given leeway to do this. Singh speaks of it being a unanimous choice — “the book topped the final, ‘order of preference’ list submitted by all three judges.” (Novelist J Devika was the third judge).

In between the lines

The discussion on the initial missing out in Salim’s case is moot but does seem strange; he had won the Hindu Literary Award for Vanity Bagh in 2014, and should have been ripe for picking in these awards too. His 20-year journey to recognition is inspiring and daunting; he wrote, re-wrote and edited his books, and received innumerable rejects from publishers and editors. Hasan shares, “Very good work is sometimes ignored.

Salim’s was for a long time till he found an agent. Being anonymous, unpublished, and from a small town, makes it hard because publishers have to judge a manuscript on its own terms than based on the profile of the writer, and that some find hard to do.” Yet, Salim considers himself lucky.

After years of collecting rejection slips, in 2010, Anees mailed a query letter and a few chapters of Tales From A Vending Machine to publishers and agents under the name of Hasina Mansoor, pretending the manuscript was the diary of an uninformed, yet hyper-literate, young clerk at a major international airport. One of the recipients was Kanishka Gupta of Writer’s Side who found home for three of Salim’s books in the first month. In two years, two of his four books won prestigious awards.

Literary fiction, et al

The standard of revenue generation does not seem to hold water here, and the print run of some literary fiction is very small. Yardsticks like lyrical writing, great storytelling and unforgettable characters are applied to them, and Singh is uncomfortable with these labels: “Distinctions can be unfair to good writers of genre or fast-paced fiction like Anuja Chauhan or Samit Basu, who tend to get sidelined in the fiction category while also getting dwarfed by the Ravi Subramanians and Ravinder Singhs in the by-popular-vote category.”

Through all he has done, Salim has broken the boundaries. As a 16-year-old school dropout, he discovered a passion for books and knew that he was going to be a writer. The journey was tough; “I started writing The Blind Lady’s Descendants during a very disturbed period. Publishers and agents rejected my first book, and I was living on the meagre income from my first job. I didn’t have enough of food or clothes. I wanted to hit out at the people I grew up with, I wanted to mock them somehow, for being so ruthlessly cynical, for making fun of my desire to be a writer.”

Literary fiction has its snobbish appeal; it reflects the prestige of its publishing house and the literary author enjoys an exalted position. Tales From A Vending Machine could be classified broadly as commercial fiction, and while it was the first of Salim’s books to find a home, he requested for The Vicks Mango Tree be released before Vending Machine. He wanted to be known as a literary author and not a writer of commercial fiction. “This despite the fact that, I always find literary fiction pushed to the least visible racks in a store while stacks of commercial fiction meet you at the entrance, glowing under LED beams,” observes Salim.

Authors have a tough act to play these days. Writing a good (or bad) book isn’t enough. They must also be smart marketing and PR people, build a strong social media platform and be actively engaged with stakeholders. But the reclusive Salim refuses to attend launches or promotions.

He says, “I did not expect to win either the Hindu Prize or the Crossword Book Award. I attended neither functions. I watched the live webcast of the Hindu Prize last year and tensed up as the announcements began. This time, I was nervous to check even Facebook/Twitter updates.”

Read and learn

Salim’s case should serve as a wake-up call to publishers to review their lists more assiduously during submissions for awards; then they can be proud of having discovered and nurtured an exceptional author. The team at Crossword must also review its performance.

According to Singh, “We were disappointed by the lack of organisation, and our initial impression was that the awards this year were more a brand-building exercise (or a “we have the brand, so let’s keep it going” exercise) than a sincere, well-thought out celebration of literature.”

Despite attempts to get Crossword’s side of the story, they declined to comment. Hasan observes, “It’s commendable that they’ve kept the award running for such a long time but it would help if the staff associated with the prize had some understanding of what a book is and how publishing works.”

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!