Continuous chest compressions during cardio-pulmonary resuscitation (CPR) by emergency medical responders do not offer survival advantages when compared to interrupting manual chest pumping to perform rescue breathing, says a study

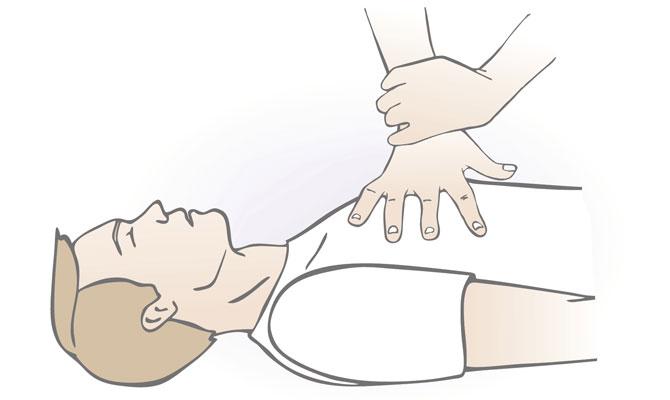

CPR

Washington: Continuous chest compressions during cardio-pulmonary resuscitation (CPR) by emergency medical responders do not offer survival advantages when compared to interrupting manual chest pumping to perform rescue breathing, says a study.

ADVERTISEMENT

CPR is the effort to restore a pulse and respiration in people whose heartbeat and breathing have suddenly ceased.

Representational picture

The study found that patients with out-of-hospital cardiac arrest who received continuous compressions were less likely to survive long enough to be transported or admitted to a hospital.

They also had fewer days alive and out of hospital during the first month after their cardiac arrest.

"Both groups did well. But it appears that patients treated by EMS providers who interrupted chest compressions to deliver rescue breathing appear to survive a bit more often," said project leader Graham Nichol from University of Washington.

"The results of this study may well change emergency medical services CPR practice," he added.

From earlier studies, emergency medical services staff and researchers were concerned that CPR methods that alternate chest pumps with a few lung inflations might reduce blood flow and possible survival.

The CPR researchers wanted to determine if continuous chest compressions at about 100 per minute, accompanied by manual ventilations at about 10 per minute, provided better results than did an approach that repeats the pattern - 30 chest pumps, halt to give two ventilations, resume pumping.

Nichol emphasized that this particular study evaluated CPR by emergency medical services providers at the scene and during transport to the hospital, not bystander CPR.

Bystanders assisting at the scene of a cardiac arrest generally perform continuous chest compressions without rescue breathing.

The study appeared in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!