Mumbai's object theatre practitioners show how everyday items can help bring to stage concepts of tyranny and propaganda

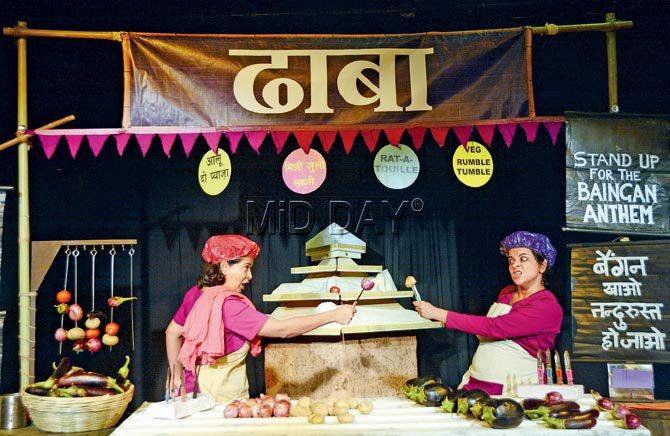

Choiti Ghosh (left) and Padma Damodaran during a staging of Dhaaba, at The Cuckoo Club, Bandra. Pic/Satej Shinde

ADVERTISEMENT

Brinjal, aubergine, eggplant - call it whatever, but you will find lots of it in a Dhaaba which prides on exclusively serving the low-calorie, high-fiber, vitamin-rich, antioxidant vegetable in varying shapes, sizes and colours. If you subscribe to the Baingan theme, you have a wide array of recipes to choose from – Baingan momos, Baingan masala, Baingan roast. But if your idea of food includes some "mili juli sabzi" of potatoes, tomatoes, onions or any other green luxuriance, you are unwelcome at the Dhaaba. If you dare to smuggle your choice of veggies into the Dhaaba pantry, be prepared to see them rumpled, chopped and trashed. Be assured that the kitchen will be thoroughly cleansed of the dirty effervescent add-ons, so that the proprietors can reinstate the eggplant in its true glory. You will be then 'asked' to rise and sing the aubergine anthem as a tribute to the purple, glossy, fresh-as-fruit appetizing Baingan. Not to forget, you will be encouraged to take a few Baingans home as you leave the Dhaaba.

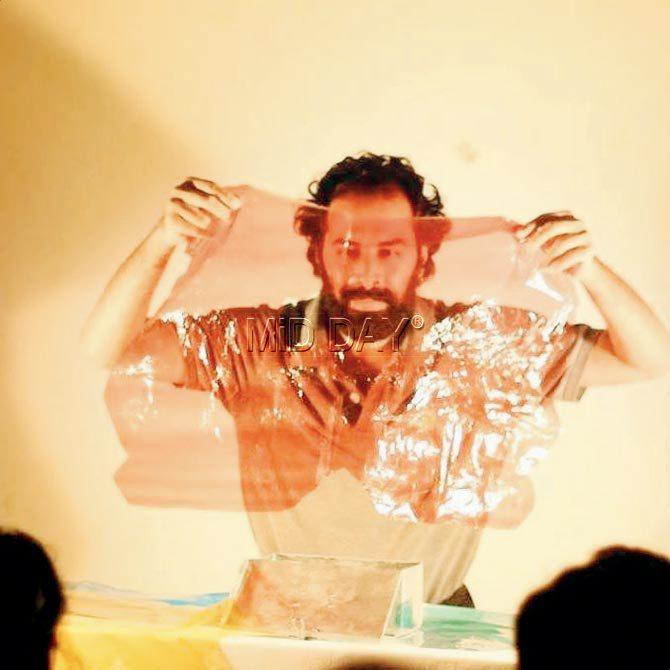

Gerish Khemani during a presentation titled Unravelling The Self, in which he played with gelatin paper in an object theatre workshop in July 2016

Baingans are objects strewn all over the floor (on the shelves, atop the kitchen platform) in the one-hour Dhaaba show directed by Choiti Ghosh, who, along with Padma Damodaran, enacts the Baingan story. On stage, Dhaaba is the fifth production of Ghosh's Tram Arts Trust which since 2011 espouses the use of everyday objects to provoke a probe into our unfolding lives. While earlier productions like Nostos, A Bird's Eyeview and Objects in the Mirror banked on shoes, mirrors, origami paper sculptures, pigeons, toy cars, the Dhaaba runs on mundane brinjals. The wonderland of objects, put together alongside human actors (illumined by music and lights) operates at two levels. First, the objects evoke emotions about the commonplace articles that we take for granted — a plastic bottle, safety pin, mobile phone cover, teakettle or a bread knife. Second, objects become potent symbols celebrating collective memories and associations. Just as a suitcase can trigger stories of migration, it can stand for a grandmother's last years; a broken lock can remind us of a failed relationship, but also a moment of unshackling.

Dhaaba is one such celebration of the ordinary-turning-extraordinary in a perceived hierarchy of vegetables. It also shows us the human tendency, and a growing one in the current Indian political context, of attaching sacredness and purity to certain articles (and in the same vein to certain lifestyle choices, approved behavioural patterns, customary faith-based practice), which inevitably imparts a negative, lesser, inferior status to anything other than that. Dhaaba brings home the rigidity of thought that comes with a pyramidal pecking order in which there is no place for the dissimilar, the new, the uncommon, and the untried. Dhaaba's eggplant enthusiast literally stabs and puckers the other veggies and gets violent (also propagandist and manipulative) in her disapproval of their nutritive value. She is at peace only when 'the other' is eliminated from the scheme of things. It is here that Dhaaba's eggplants become status symbols, cultural identity markers, segregation tools that isolate the superior from the banal.

The August edition of Museum of Ordinary Objects is being built with crowdsourced objects. Soon, drop-off points will be set up for quicker entries, says Karan Talwar of Harkat Studios (who has collected 26 items so far)

Ghosh's Dhaaba, put to life by dramaturge Sameera Iyengar, is a fictional-yet-educational space where objects wake us up to our infinite capacity of dividing the world in ranks; and not embracing it in totality. In fact, Ghosh sees object theatre as an opportunity to practice egalitarianism in theatre and life. "With each play, I have found myself moving closer to ordinary articles and away from theatrical material or props. Ordinary simple actions using objects help in the exploration of unexpected depth," says Ghosh, who has mounted the Dhaaba six times, primarily in intimate experimental spaces like Harkat Studio, Cuckoo Club, Brewbot Pub and Clap Malad. Tram Arts is now planning to take the Dhaaba to larger venues after a short summer break aimed at reinventing the Dhaaba with new object ideas that have come from audiences since its launch in November 2016. Like it has happened in the case of the earlier plays, Dhaaba will also map the other possibilities of presenting the same story. "Mumbai is a sea of objects — mass-produced and mass-consumed — which helps us to evolve our narrative thread and our object vocabulary," says Ghosh.

While Dhaaba's insides are in for a makeover, some of its objects may end up in another setting — the MOOO (Museum of Ordinary Objects) which is being built with crowdsourced objects, due to open in Mumbai this August. While two earlier editions of the museum rose from curators' collections, the new assortments are offerings of Mumbaikars, a couple from New Delhi, two from Berlin and two from Munich. As the deadline nears, drop-off points will be set up for quicker entries. Hoarders have been signalled on social media to share their little-big objects with a vital connect. The inventory seems interesting at this point: a Relaxo Chappal, an opened tin of fruits, a geometry box, an asthamatic's inhaler and a squeezed tooth paste tube. Harkat Studio Director Karan Talwar (who has collected 26 items so far) says MOOO is a democratic space where the collections will decide the theme; objects will share the space with handwritten captions, mapping the significance and arrival in the collectors' life as well as the instances of shared ownership. Talwar recently deconstructed leftover objects in an abandoned house in his short film And Sometimes, She Loved Me Too.

Since Mumbai doesn't have full-time objecteurs like Ghosh, the upcoming Do It For Yourself Workshop under the aegis of Tram Arts is important. Aiming to instill object sensitivity at an early age, Tram has conducted orientations for students and teachers in a formal classroom. These workshops make the impressionable minds cognizant of the shiny, pre-packed, identical and disposable objects they use without much thought. But the DIFY initiative is for theatre practitioners, much like last year's workshop in which two performers tried to create meaning by negotiating with objects placed in the performance space.

For instance, actor Gerish Khemani used a single shoe to tell a story of urban loneliness and then recycled pairs of shoes to show the oppressive nature of schooling. Similarly, Vikrant Dhote, a performer interested in the theme of gender and sexuality, highlighted male power and female suppression by using an orange, beetroot, kiwi and potato — all fruits and vegetables that could be peeled and undressed.

Interestingly, Tram video records the DIFY participants' workshop process and also provides an 'outsider eye' (dramaturge) as a guide in the activity. In other words, the makers of the Dhaaba are set to train a few more hands to appreciate the subjects in the world of objects, which of course, includes colorful purple Baingans. Sumedha Raikar-Mhatre is a culture columnist in search of the sub-text.

You can reach her at sumedha.raikar@gmail.com

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!