INDOLOGY is the study of India. Currently, in many universities, it is called South Asian studies, as there is confusion between political India and the Indian sub-continent. Today, we can identify four different schools of Indology: European, American, Diasporic and Indian.

INDOLOGY is the study of India. Currently, in many universities, it is called South Asian studies, as there is confusion between political India and the Indian sub-continent. Today, we can identify four different schools of Indology: European, American, Diasporic and Indian.

INDOLOGY is the study of India. Currently, in many universities, it is called South Asian studies, as there is confusion between political India and the Indian sub-continent. Today, we can identify four different schools of Indology: European, American, Diasporic and Indian.

ADVERTISEMENT

The European school pioneered Indology in the 18th century, and comprised mostly of German and British scholars. They translated Sanskrit texts and tried to construct the doctrine, as well as the history of Hinduism, along the lines of Christian doctrine and history. Initially, many saw Hindus as the ‘noble savage’, yet to evolve scientifically. Later, influenced by racial theory, many spoke of the Aryan invasion of India, equating privileged Hindu communities with invaders, no different from Muslims and Europeans, and so stripping them of all moral high ground. Thus, was caste explained and colonisation justified.

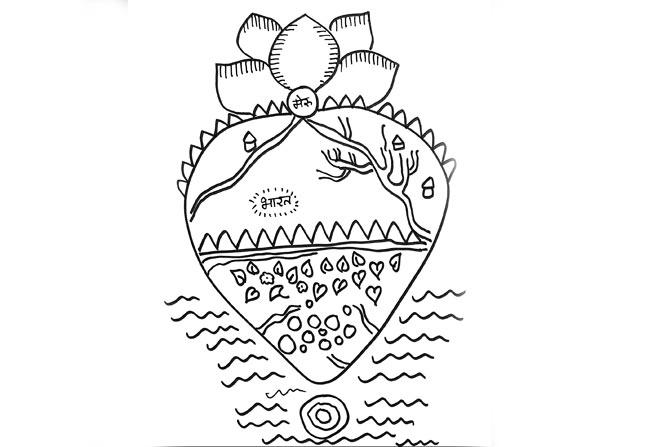

Illustration/Devdutt Pattanaik

The American school of Indology emerged, challenging colonialism and celebrating the subaltern, the categories overlooked by the Europeans. Thus, greater attention was paid to regional languages, to Dalits, to women, to hijras, to displaced tribes and unemployed craftsmen. Most things in India were seen through the lens conflict either between religions or caste. Like the European school, they continued to explain everything in terms of ‘good’ egalitarian Buddhism and ‘bad’ hierarchical Brahminism. Hindu customs and beliefs were psychoanalysed, and suddenly Shiva-linga was reduced to ‘phallic-worship’. Despite the prejudice, it expanded our understanding of India, uncovering numerous new bodies of knowledge.

The Diasporic school of Indology has emerged in recent times amongst a section of first and second generation economic migrants to Europe and America, who have suddenly found themselves burdened with the task of explaining Hinduism and India to their children, and to people abroad. They feel judged, mocked and are often embarrassed of how India is perceived on the world stage. They yearn for pride and often succumb to Right Wing propaganda that endorses the Vedic world as magical and perfect — before the arrival of the Muslims and Europeans. In this version of Vedic India there was no poverty, discrimination or caste. Any challenge to this view is seen as anti-national, data notwithstanding. The irony that Non-Resident Indians (some without even Indian passports) are questioning the patriotism of resident Indians is lost on few. Mercifully, a more mature Diasporic Indology school, based on critical thinking, is gradually emerging that does not indulge in victim complex and seeks a more liberal understanding of Hinduism, unafraid of Indian complexities.

That leaves the India school of Indology, which wants to balance the outsider’s perspective with the insider’s perspective. But, since much of academia depends on European and American universities for training, templates and funding, breaking away from the Western paradigm has not been easy. Many have slowly challenged the assumptions, and approaches of Western scholars: the tendency to value the textual over the lived experience, and the material over memory and myth. They find themselves attacked by European/American Indologists as being too defensive and apologetic and by Right-Wing Diaspora Indologists for being ‘colonial sepoys’.

Each of these schools is dealing with its own inner demons while trying to solve the puzzle that is India. The more we observe the observers, we realise we must be careful of people who claim to be ‘scientific’ and ‘objective’, whether on the Left or Right. Words such as these mask assumptions and agendas of Indologists. In academic circles, it is a common practice to discredit earlier scholars by claiming earlier researchers had an agenda, and the current researchers are agenda-free. But the fact is, even the most authentic and empathetic contemporary scholar will turn out to have an agenda, which will only be revealed by future researchers. Having an agenda does not make the observer ‘evil’ or invalid. Everyone has it and, most of the time, it is unconscious, awaiting discovery.

The author writes and lectures on the relevance of mythology in modern times. Reach him at devdutt@devdutt.com

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!