Thai aesthete and collector Rolf van Bueren who sources material from south Asiatic countries to turn them into objets d’art, on how to sell an ancient craft to a new audience

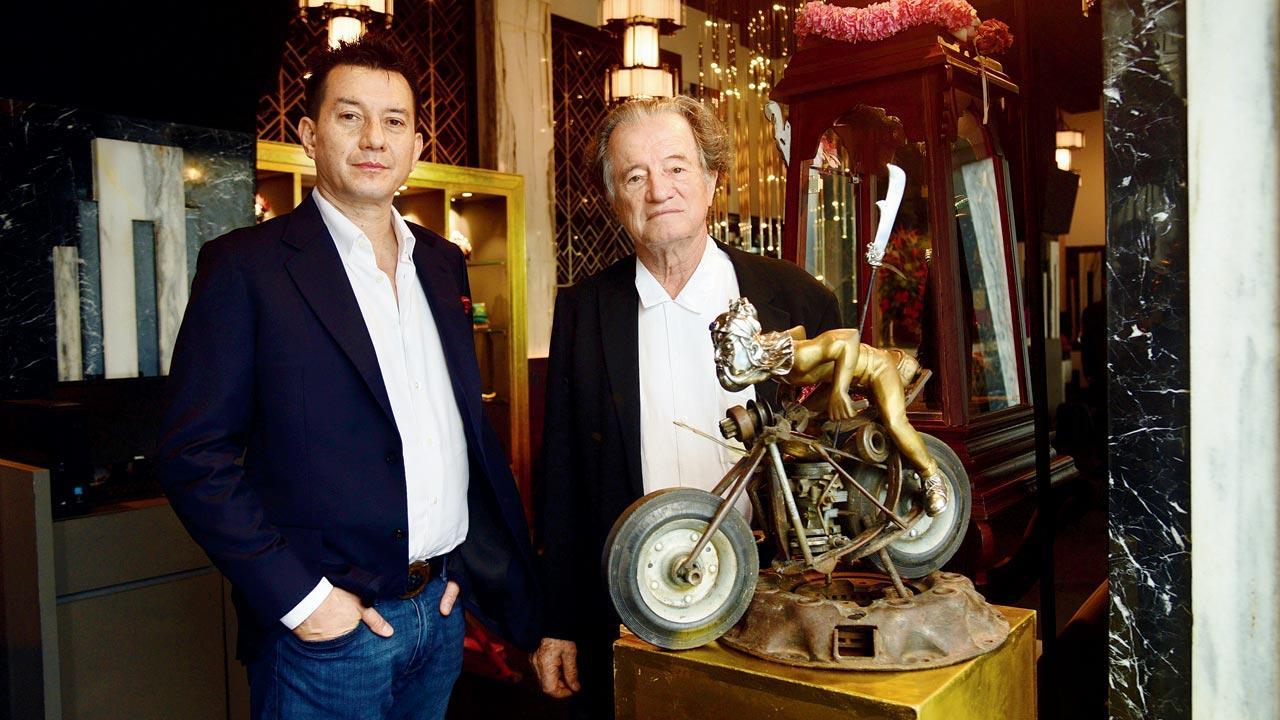

A silver-faced Chinese Guan—protector of a home—speeding on a motorbike is made out of bits and bobs. Rolf von Bueren and son Nicklas, who are exhibiting their collection at Jia the Oriental Kitchen, Colaba. Pics/Pradeep Dhivar

Rolf von Bueren first came to India in 1964, and his first buy was a jamevar shawl from Kolkata. Since then, he has been visiting the country three to four times a year to work with the craftsmen and source textiles. This time around, he has come armed with a few Sanskrit words. “I have been asking people what they mean, and I haven’t got an answer,” says the genteel octogenarian. “In Thailand, many people would know that some of these words mean. In Thailand, all royal ceremonies start with Brahmin priests reciting the prayers, then come the Buddhist ones. Even the written Thai language is closer to Sanskrit than Hindi is.”

ADVERTISEMENT

Born German, Rolf has done “a lifetime of meditation and other exercises” to shed “the aggression of the West”. “The Thai are very gentle people,” he says of his adoptive country. Looking at that high forehead, soft speech and deep bow during introductions and farewells, it’s hard to imagine him as anything other than a connoisseur of fine things. Yet he was sent to Thailand in 1962 to set up a chemical plant. “Then I was sent to Korea,” he says, “but the country was too hard; no judgment.”

He met his Thai-Scot wife Helen, and together, they set up Lotus Arts de Vivre: An exclusive travelling collection of jewellery, personal items and artifacts. Rolf and his son Nicklas are in Mumbai to open a brick-and-mortar outpost in Colaba which will see other aesthetes by appointment.

The van Buerens travel as a family (almost 200 days in a year), sourcing material from mostly south Asiatic countries and giving them their distinctive twist—a leather bulldog with veins of silver, 100-year-old bamboo mats folded into clutches, covered with cloth and hand-painted; the trunk burl of a tree turned into a table. “You see swirls instead of rings,” Rolf points out. Gigantic bowls made out of cinnamon sticks, rudraksh gilded and strung to form a necklace.

Scarab wings, such as the ones used to make this necklace, remain vivid for a long time

Scarab wings, such as the ones used to make this necklace, remain vivid for a long time

He has just ordered a bunch of shibori (bandhej/ bandhani) scarves for clients at the end of the year. Rolf’s introduction to the weavers and artisans of India came through textile conservator and cultural historian Martand “Mapu” Singh. He still works with weavers and artisans introduced to him by Mapu, as he does with his contemporaries, textile scholars and conservators Rahul Jain and Rta Kapur C8histi. Rajmata Gayatri Devi was a gateway into the grandeur of royal Rajputana, and she inaugurated many of the van Buerens’ exhibitions. “Mapu told me that the best shibori has 25,000 knots per square metre,” says Rolf, eyes wide as if he was just told this bit of trivia. “Can you imagine how fine it must be? You want anything in textile, you come to India. You also have the best craftsmen for kundan setting, stone inlay, bidri-work. That’s why we come here. Why reinvent the wheel?”

Also Read: Mumbai: A city of dreams… but not for all

Being such a frequent visitor, Rolf has also been witness to the shrinking pool of artisans. “You used to have a huge number of handloom weavers; now only about 20 per cent remain. If you go to Benaras and see some of the weaving, it’s terrible. All the young people have left ,” he says. “In Jaipur, which was a stone-dedicated city, we saw artisans glued to their screens when the stock exchange was booming. The stone layers did not care about their business anymore! There was no new stock. The splendour is slowly fading away. There are a few young people who are following their parents into the trade; we work with them. The challenge of the lack of artisans is what my sons [Sri and Nicklas] will have to face.”

Bamboo mats turned into clutches, with a rare bamboo root as handle

Bamboo mats turned into clutches, with a rare bamboo root as handle

Nicklas is with Rolf on this trip. Sharp in a suit, he has three bracelets on one hand—braided leather with animal-head clasps in silver. His personal agenda in India is to check out textiles and have some suits made.

His professional task has been to build an online presence for their endeavour, trying to distill 1,000-year-old craft processes into 1.5-minute attention span of the new clientele. Astonishingly, the three-year-long COVID 19-imposed lockdowns, during which the family did not travel, led to a spike in sales. “People were stuck in their homes. Their attention span was devoted to their home country. They were not flying out every other week, so they had the time to understand our objets d’art. People wanted to know and learn about what they didn’t know before” explains Nicklas. “The most expensive thing we sold was worth 2,25,000 dollars to a customer in America. Both sons manage the marketing, online presence and growth of the business, while Rolf remains the taste-maker. “But we still have physical stores,” says Nicklas, “Because people want to touch and feel the products. So we are trying to find a balance between the new way of selling and the old.”

Made in China, this bowl has 60 to 80 layers of lacquer infused with cinnabar for colour

Made in China, this bowl has 60 to 80 layers of lacquer infused with cinnabar for colour

Their current collection is on exhibition at Jia the Oriental Kitchen in a Colaba bylane, although not on sale. On display is jewellery made of iridescent blue and green scarab beetle wings. “We have millions of them on tamarind trees,” says Rolf, as he walks us through it, “And they die and fall down, from where we collect them. They don’t fade. There is a 11th Century vase in Japan made of scarab wings, and the colour has not dulled.”

There are gold nuggets, reminiscent of those found in the USA 150 years ago, strung into a necklace. “We’ve made them lighter,” says Rolf. His respect for the process of each of these things of beauty sets him apart from those who hoard them solely for their price tag. There’s a large carved cinnabar basin from China. “It has 60 to 80 layers of lacquer,” Rolf tells us. About a lacquered Japanese tray he says, “These are polished with ash, which costs $5,000 a kilo.”

And there is wood. So much wood. The gnarled root of a bamboo—rare to find—is the handle of a hand-painted purse. Root of a teak tree turned into a table, hardly-seen rosewood (the felling of these trees is illegal in most countries) trunks. “Rosewood trees are practically finished,” Rolf says. “They used to be sold by the tonne; now they are sold by the kilo. Even the large coconuts shells that priests used for alms, they are much smaller now.” Then there are “laugh pieces” such as silver-faced Chinese Guan—protector of a home—speeding on a motorbike made out of bits and bobs. When the van Buerens need to modernise a piece, as in the case of clutch purses, they look at it as another opportunity to shine a spotlight on a craft. To create a thing of beauty “Now everything needs to hold a phone,” Rolf explains, “and the lady might have a glass in one hand, and a plate in another. She needs a strap on her purse. So we made detachable hand-painted straps. But we wanted to cover the clasps. So we camouflaged them using little silver lotuses. We had to ensure the metal wasn’t so thin that it would break. The edges should not poke the person. It takes skill.”

Turn to Nicklas with the worry of crafts dying out, and he says, “Younger people have an interest. It’s about how to get it out of them. People travel and they realise that some brands have stores in every airport. They understand that they want to be different from their friends and peers. We’ve got to get to them.”

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!