Questions around the why of conversions to Buddhism continue to be raised in India. The answer depends on where you stand—in a SoBo living room struggling with attachment or a village where you are thrashed for celebrating the Goddess

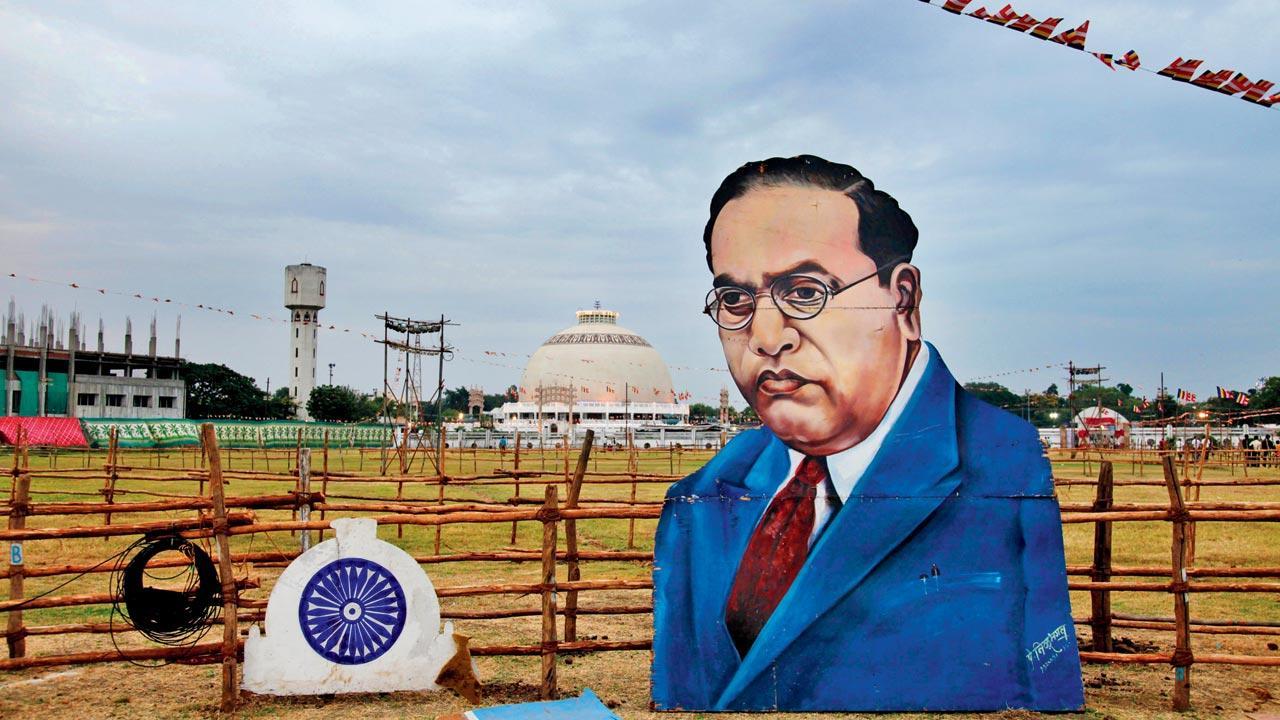

A cutout of Dr BR Ambedkar at Deekshabhoomi during the annual celebration of his conversion to Buddhism in Nagpur. Ambedkar converted to Buddhism along with 3,80,000 of his followers on October 14, 1956. Tens of thousands of Buddhist pilgrims visit Nagpur during the week of this celebration. Pics/Getty Images

There was once a tree under which Siddhartha gained enlightenment and became the Buddha. Then there was the tree under which Dr Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar spent the night after his landlord threw him out for being a Dalit.

ADVERTISEMENT

After years of trying to uplift the downtrodden castes, Babasaheb Ambedkar realised that political, economical and social opportunities would always be denied to them in a caste-driven Hindu society. The only way out was to get out.

The architect of the Indian Constitution studied world religions for 20 years, and narrowed down to two choices: Christianity or Buddhism. The latter aligned more with his values of equality and fraternity among all humankind, and more importantly, it rested the powers for evolution with the individual, and not a person in the sky. One of the 22 self-crafted tenets of Neo-Buddhism is: I shall not allow any ceremonies to be performed by Brahmins.

And so, he crafted Neo-Buddhism or Navayana Buddhism, converting six lakh followers along with himself on October 14, 1956. What sets Navayana apart from Mahayana, Theravada and Vajrayana sects of Buddhism is the slashing away of any umbilical cord connecting it to Hinduism and its airtight caste system that no one can escape, even after several rebirths. The other tenets say: I shall have no faith in Brahma, Vishnu and Maheswara, nor shall I worship them; I shall have no faith in Rama and Krishna, who are believed to be incarnation of God, nor shall I worship them; I shall have no faith in Gauri, Ganapati and other gods and goddesses of Hindus, nor shall I worship them; I do not believe in the incarnation of God; I do not and shall not believe that Lord Buddha was the incarnation of Vishnu. I believe this to be sheer madness and false propaganda. The most important tenet is: I shall believe in the equality of man.

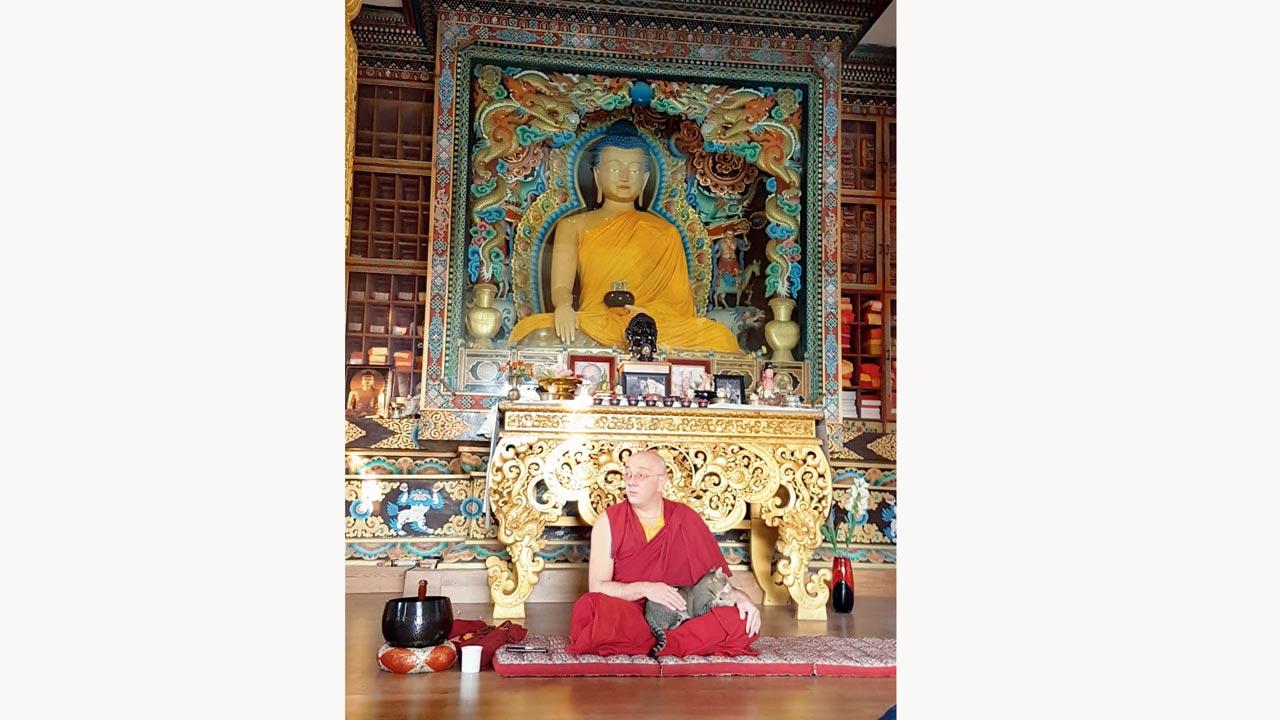

Karma Jingpa

Karma Jingpa

Unlike the other mainstream forms of Buddhism—The Nichiren Buddhism chanted by groups in the living rooms of Juhu, Bandra and South Mumbai; the exotic Tibetan Buddhism (a mix of Mahayana and Vajrayana) spreading through refugee pockets in the Himalayan states, attracting movie stars and white working class heroes alike, and the stark Zen Buddhism co-opted into a design aesthetic—Navayana Buddhism emits an odour of struggle and centuries-old injustice.

Navayana was supposed to be a getaway car that took the Dalits towards dignity, education, egalitarian employment, and injected them into mainstream society. And yet, Rajendra Pal Gautam, Aam Aadmi Party leader and a minister in the Delhi state government was bullied by the ruling party to hand in his resignation after he attended a mass conversion earlier this month.

Followers of Ambedkar buy statues of Lord Buddha and Dr Ambedkar after paying their tribute on his death anniversary, at Chaityabhoomi, Shivaji Park, Dadar

Followers of Ambedkar buy statues of Lord Buddha and Dr Ambedkar after paying their tribute on his death anniversary, at Chaityabhoomi, Shivaji Park, Dadar

With a focus on Ghar Wapasi (reconversion to Hinduism), the act of choosing a religion for dignity is treachery. While the Right to Education and reservations have uplifted and created opportunities for Neo-Buddhists in urban cities, in villages, they are still lynched for riding a horse on their wedding day, or, as in the case of a 15-year-old from Uttar Pradesh, thrashed by the teacher to the point of death for writing the wrong answer.

Last week, 250 Dalits converted to neo-Buddhism in Rajasthan. They had, a few weeks earlier, renounced Hinduism by immersing idols of Hindu gods and goddesses in the river. This mass protest came after two Dalit men were assaulted for planning an aarti of Goddess Durga during Navratri.

The chanting of the Lotus Sutra, central to Soka Gakkai, takes places mostly in the city’s drawing rooms. Barely anyone joins resident monk of the Nipponzan Myohoji Buddhist temple in Worli, Bhiksu Morita, for the morning and evening ritual. Pic/Ashish Raje

The chanting of the Lotus Sutra, central to Soka Gakkai, takes places mostly in the city’s drawing rooms. Barely anyone joins resident monk of the Nipponzan Myohoji Buddhist temple in Worli, Bhiksu Morita, for the morning and evening ritual. Pic/Ashish Raje

“The Dalits are the second-most discriminated group after Muslims,” says Neo-Buddhist scholar Dr Anil Yadavrao Gaikwad. “After the strong example set by Dr Babasaheb Ambedkar, most Dalit youth seek education. They, in fact, rank second on the [mainstream] education scale after Brahmins—96 per cent of the neo Buddhist population in India is educated. A Dalit will gain education through any means possible—correspondence, night school, distance education. However, if the interviewer at a job consciously or unconsciously discriminates based on caste, you are less likely to get the job. In Maharashtra, our last names give away our caste: Kamble, Gaikwad. Even today in Gujarat, you cannot rent an apartment in dominant caste society area if you are a Dalit.” In 2020, 20 Dalit women engineers called out caste discrimination in the Silicon Valley.

Under the current political climate, most neo-Buddhist leaders fear that their constitutional reservation for education and jobs may be revoked at any time. “The political mindset is still largely Brahmanic and implemented at the grassroot level,” says the Mira Road-based Finance consultant. “The AAP should have stood up for Rajendra Pal Gautam, saying his religion is his personal matter. It is a constitutional right.”

Anil Gaikwad, Neo-Buddhist scholar

Anil Gaikwad, Neo-Buddhist scholar

As a pious neo-Buddhist, the neo-Buddhist scholar renews his pledge every morning to not kill a living being, to not steal, to abstain from sexual misconduct, to abstain from speaking lies, and to abstain from intoxication. “Buddhism and Jainism are the two atheist religions,” he says, “There is no concept of god. The ultimate aim is evolution of the human soul.”

This is the core idea of all flavours of the 2,500-year-old belief system. To evolve, one must stop being slave to ones thoughts and emotions. To break free from that yoke, meditation is the answer. High up in the monasteries in Bir-Billing, Spiti, Leh-Ladakh, and the valleys of Arunachal Pradesh, are monastic orders dedicated to preserving Tibetan Buddhism.

“For many centuries,” says Karma Jingpa, an ordained monk or bhiksu of the Tibetan Buddhist tradition, “Tibet had closed it borders to other countries and cultures. Due to this isolation, their form of Tibetan Buddhism grew in a unique way after it spread from India.” A mix of Mahayana and Vajrayana Buddhism, it lays great stress on the guidance of a guru. “A teacher is your refuge,” says the American-born Jingpa, who was ordained in 2010, and teaches in Bir, Himachal Pradesh. “He is the first one to give you a glimpse of your mind. He will help you watch your thoughts in meditation, like one would in a cricket match without taking sides.”

Tibetan Buddhism has a Hindu-like flavour with many realms, and gods and goddesses such as the various Taras (removers of obstacles). While some understand these realms to be literal realities where one takes births in and works through their karma, Jingpa says they can also be states of mind. For instance, the Animal realm is one of impulsivity, while the Hungry Ghost realm is that of attachment and desires that cannot be quenched.

The vehicle to this ‘cricket match’ is meditation. “By learning to watch your thoughts and not stay in any realm, the ego is not allowed to rise,” says Jingpa, “You see it for what it is, a risk-assessment tool, and how it influences your decisions. When you come out of the meditation, you act actively to purify your karma. You think before speaking, you think about, ‘how can I not add to the karma’. You also pay attention to the moment and the person in front of you and ask: What does she need of me? It could be just a listening ear, candour or advice.”

The other crucial trait to cultivate is non-attachment. For example, once you move on from the person who approached you, you must not be attached to whether or not they took your advice. “You dedicate the merits of a meditation to your guru,” says Jingpa, “and once you are off the [meditation] pillow, you don’t stay attached to the last session. You may have experienced bliss in this one, but all the causes and conditions that existed for that to happen may not occur the next time you sit down to meditate.”

He likens kleshas (negative karma) to Jenga blocks stacked very high. One moves through life looking at each situation as an opportunity to remove one block, and instead of putting it on top of the stack, it goes away.

This practice of pausing to think before one speaks or acts is also what the Soka Gakkai community practices, only this strain of Buddhism lays import on togetherness. Structured like a pyramid marketing scheme, it has chapter heads and district heads who arrange group chanting sessions and visit those in need of a spiritual ritual boost at their homes. They take requests for praying on behalf of others, and at each meeting, members give testimonials of how their worries are diminishing to encourage others to stay on the path.

Its practitioners tend to be urban, and the upper middle-class. Actor Tusshar Kapoor and his sister Ekta Kapoor are known to attend the Juhu chapter. Playwright and novelist Eve Ensler (of the Vagina Monologues), now known only as ‘V’, credits this practise with helping her heal from years of sexual abuse by her father when she was a child.

The kernel of this practise is the chanting of the Lotus Sutra—Nam Myho Renge Kyo—for neutralising one’s karma. It is usually chanted by focusing on a Gohonzon—a scroll with the Lotus Sutra written on it. With no other daily ritual than to chant this for a personally fixed amount of time, this is the religion for the urbanite in a hurry. And also for those tired of overbearing dogma and strict rules. “You can chant, Nam Myho Renge Kyo, and still go worship Ganpati or offer namaz,” says Amita Gandhi, District Chief for the Juhu Chapter. Unlike Tibetan Buddhism which takes the path of recognising the complex physical world for the impermanent illusion that it is, or Navayana, that strives to change the world and social circumstances of a believer, Nichiren Buddhism encourages one to engage with the world and equips the believer with a toolbox. It says Buddhahood is possible in this very lifetime.

“Our Buddhism does not say that the Buddha was someone special and unique,” says Gandhi. “It tells us there is a Buddha within all of us, and the aim of life is to strive to achieve that Buddha state characterised by compassion. And the trials and challenges we face in life are situations to evoke this Buddhahood. It teaches you to think of the other person.”

A central belief to this system is that the outside world reflects one’s inner world. A short-tempered or rude person is suffering inside. His or her reactivity is a manifestation of that ‘illness’ and s/he needs our compassion, and not escalation. “We learn to stop and think about the other person, and see the Buddha in them too,” says Gandhi. “We then respond accordingly—with calmness and compassion, getting closer to our own Buddhahood”.

The rituals of most forms of Buddhism are common—meditation as a path to self-awareness and steadfastness in the face of volatile emotions and circumstances; and forgiveness, first of ourselves and then of others. “You even forgive yourself for not being able to forgive,” says Jingpa. And the crux of the faith: That redemption is possible. And you can do it for yourself.

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!