Lines blur between influencer and citizen journalist, as Palestinians bring raw, compelling stories to reshape the narrative around the Gaza conflict

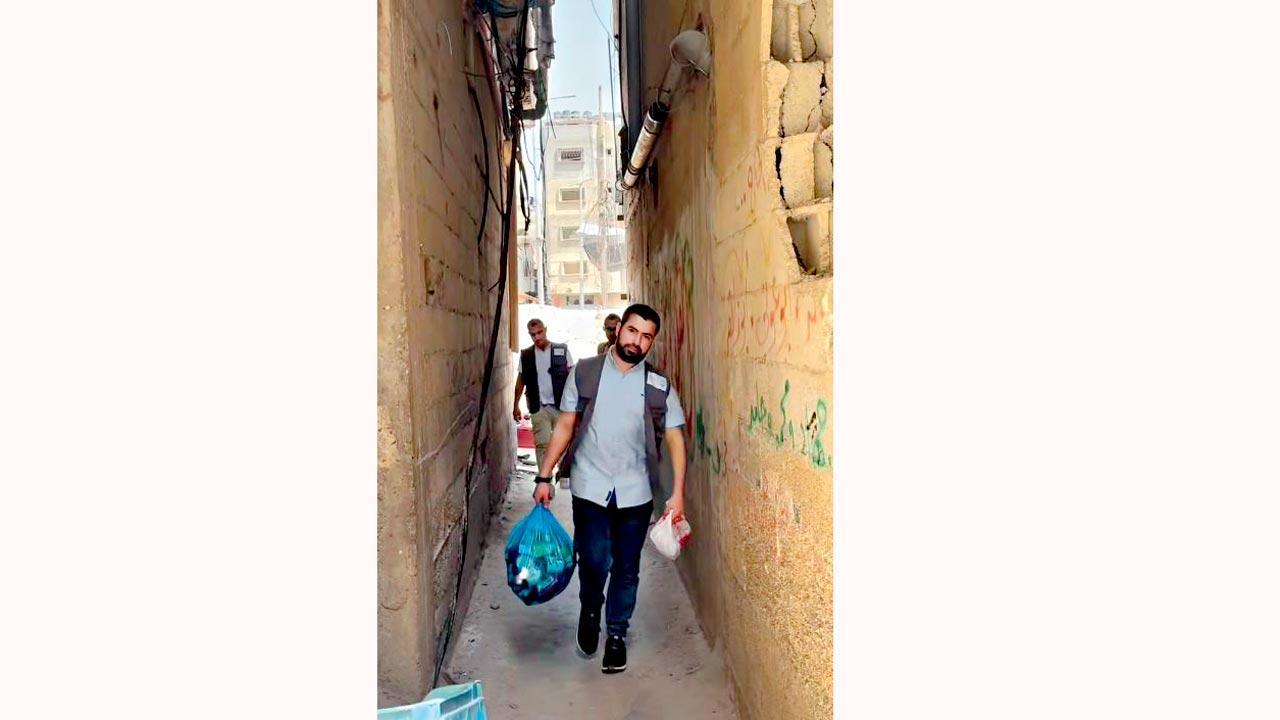

Ayman Al-Hassi, influencer and citizen journalist from North Gaza. Pic/Instagram

Ayman Al-Hassi, 36, was a freelance photographer before catastrophe struck on October 7, 2023, when Israel launched a full-blown attack on the Gaza Strip as a retaliation to the attacks carried out by Hamas a day before.

ADVERTISEMENT

Armed with his expertise in photography and a SIM card from the UAE that was still receiving signal in the war-struck territory, he decided to take to social media to put out content about the strife. Instagram was his first choice—an app he had been using for years.

Eight months on, Ayman has garnered over 77,000 followers on Instagram. He makes reels of himself doing relief work such as bringing food to people, and sometimes even cooking for them as rockets and missiles continue to land around him.

But he, and the people he is helping, remain unfazed by the attacks.

Subramaniam Vincent, Director of Journalism and Media Ethics; (right) Influencer and cook Tanzin

Subramaniam Vincent, Director of Journalism and Media Ethics; (right) Influencer and cook Tanzin

Ayman is just one among hundreds of young Palestinian individuals who have refused to leave the war zone, choosing instead to serve their people by recording their struggle in the war and taking these stories to the rest of the world. Today, they aren’t just social media influencers—they are a new breed of storytellers that has emerged from this war zone. With smartphones and social media as their only tools, they have doubled down as citizen journalists.

Today, the world knows the plight of Gaza, where even the Red Cross and Doctors Without Borders cannot operate (are operating under extreme restrictions). And the credit goes to the incredible efforts of these influencers. They are perhaps one of the most vulnerable groups of people in the world, but unlike international reporters, they have the advantage of being on the ground, as well as their comfort with the local language.

Citizen journalists have become the primary sources of graphic and often horrific war news that mainstream media censors. Their unfiltered glimpses into their world are reshaping the narrative around the conflict. They are also responsible for garnering support from the international community as they document reality from the war-torn region every day.

“My Instagram reels are not just updates from Ground Zero,” Ayman says. “The relief work we do soothes the wounds of those facing the brunt of what is now being called ‘genocide’.”

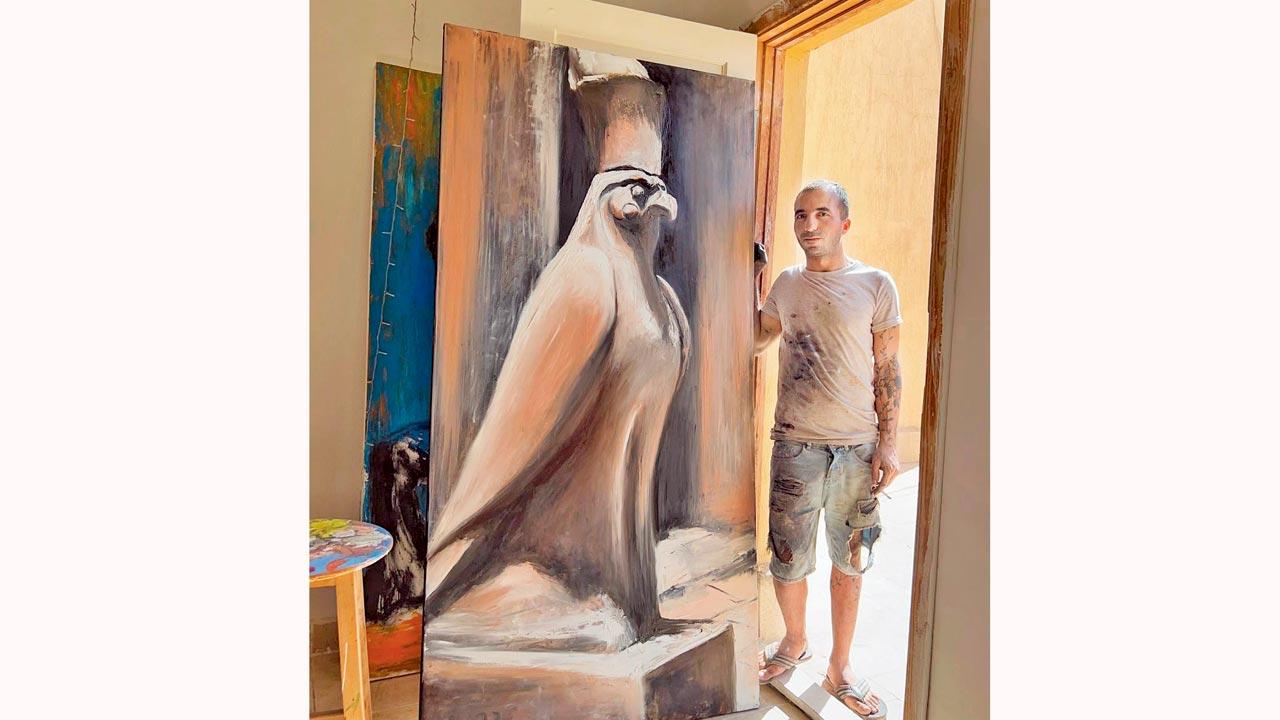

Painter and illustrator Yassin posing with his artwork. Pic/Instagram

Painter and illustrator Yassin posing with his artwork. Pic/Instagram

Ayman and his peers are not just witnesses—they’ve also sustained injuries while filming their posts.

The 36-year-old, young and with his entire life ahead of him, could have crossed the border to a safe zone. Yet, he stays put. “I want the world to understand and know that the people in Gaza love life and freedom, and strive for it. These people are living in very difficult conditions, digging into rubble to get food and water daily,” he says.

The lensman says that while not all succeed in monetising their social media posts, most gain thousands of followers and succeed in garnering global sympathy. In addition, Ayman’s and his peers’ videos have become a source for news organisations, too.

“The Israeli Army does not distinguish between journalists, civilians, or even healthcare workers,” Ayman explains. “But it is my homeland. And I strive to capture the beautiful as well—the smiles of children, the energy of youth, and the rehabilitation campaigns carried out by volunteers.”

Shahd Safi and her family

Shahd Safi and her family

So far, over 37,000 people have died in the Israel-Hamas war that began last October. Despite the presence of traditional media on the ground, it is the citizen journalists’ voices from Palestine that are sharing harrowing stories from the war with the rest of the world, especially the Gen Z demographic, which are the biggest content consumers on Instagram and Facebook. Ayman says these “citizen journalists” are doing what traditional journalists often cannot do due to the risks involved.

Shahd Safi, a 23-year-old Gaza native, found a lifeline in social media, after crowdfunding helped escape to Cairo, Egypt, along with her family on March 3 this year.

Shahd—who wears multiple hats as a human rights activist, an Arabic teacher, and a journalist—emphasised the importance of English and social media skills for Palestinians. “I grew up in Gaza. One of the most important skills one could have there is to know English and social media. Those who speak English are more successful, both on social media and in general. Palestinians have been vocal about their struggle and plight, but many do not have the right terminology to communicate with the rest of the world,” she says.

Like many others, Shahd has faced content restrictions. “Most of the social media is owned by pro-Zionist groups, and the algorithms are not supportive of the content people post. Most of it is automatically suppressed,” she explains. Despite these challenges, those who follow and support Palestinian accounts continue to receive crucial information that mainstream media can’t provide.

Shahd started a social media campaign to gather funds for her family’s escape from the war-torn region

Shahd started a social media campaign to gather funds for her family’s escape from the war-torn region

Shahd also shed light on the surveillance by the Israeli government on Palestinians’ phones. “The amount of penetration the Israeli government has on our phones is beyond one’s imagination. Even if our phones are switched off, before bombings, they start getting warning alarms to vacate the area. Sometimes, these warnings are fake, too, to keep Palestinians anxious and on edge,” she claims.

Also in Cairo, painter and illustrator Yassin remains vocal about the Palestinian struggle. Surrounded by Gazan refugees, Yassin channels his anger and frustration into his art. He shares his illustrations with over 46,000 followers on Instagram, transforming horrific scenes from Gaza and the West Bank into powerful, symbolic artwork.

“I regularly see horrific scenes from Gaza on local WhatsApp groups, and in the news. Instead of sharing the graphic images, I turn the people’s plight into art and share them on my Instagram feed,” Yassin explains.

Yassin’s friend Mohamed Yehia, who visited Gaza nearly 5 years ago, adds, “It (Gaza) is like a prison. It was one of the saddest places even before the latest war. The atrocities on people who live there are terrible, so it is important to pay attention to the content coming out of that place. Social media has been very helpful in recent years when it comes to educating the rest of the world about Palestine.”

Citizen journalism is not without its pitfalls though, with credibility remaining a major concern. “Social media is a crucial source of information, but it comes with risks. For example, relying on a ‘blue tick’ for authenticity can be precarious,” says Dhiman Chattopadhyay, former journalist and currently an associate professor of journalism at the Shippensburg University of Pennsylvania.

At the same time, there’s no denying the power that such raw reportage holds. “In modern times, even trained journalists often turn to citizen journalists for information, as traditional scribes may not be able to provide as authentic content due to political and ownership diktats that bind them to certain narratives. Citizen journalists are unbound by these constraints, and hence, can offer raw and genuine content. In cases like Ukraine and Gaza, citizen journalists and content creators are often present at the spots when many mainstream journalists may be absent. These individuals provide first-hand information,” he says.

There is another advantage to unfiltered content, too. “There may be an inherent bias in organisations where content undergoes multiple layers of checks. In contrast, social media content creation relies solely on the creator’s conscience as the check,” says Chattopadhyay.

When asked how content creation on social media and citizen journalism are different in war-hit Palestine and Ukraine from the rest of the world, Dhiman said, “People in Palestine and Ukraine are fighting for their lives, and what they are doing is remarkably admirable. They are accomplishing what traditional journalists cannot due to the risks involved. Some organisations refuse to send reporters because of life threats, but these content creators, who are now serving as citizen journalists, are driven by patriotism, and strive to improve their countries’ situations.”

He also added, “While content creators in Ukraine may focus on Russian aggression and the ones in Gaza on Israeli bombings, they also address local issues related to health and sanitation. This amounts to reportage. These citizens may have biases, but that does not diminish the authenticity of their reports.”

“As a trained journalist, sometimes one might have to see through some of the information that may stem from personal grief and trauma, which is often the case in war zones. A trained journalist might tone things down, but the raw reports from these areas are ‘invaluable’. If there were a Pulitzer Prize for citizen journalism, these individuals collectively deserve it,” says Dhiman.

The Arab Spring movement is largely held to be the first revolution in which social media played a huge role. Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube were instrumental in organising protests, sharing real-time updates, and broadcasting footage from the ground during the Arab Spring Movement that began in 2010. Citizens across Tunisia, Egypt, Libya, Syria, and other countries used social media platforms to document and spread awareness about their uprisings against authoritarian regimes.

“The Arab Spring is a great example in which citizen journalists played an important role. Although not led by social media, the Arab Spring was significantly spread through it. It was one of the first movements where social media and content creation played a major role,” says Dhiman.

Subramaniam Vincent, co-founder of civic media platform Citizen Matters and director of journalism and media ethics at Santa Clara University in the US, says, “The footage that came out of the Arab Spring in the early wave in Tunisia, Egypt, etc, had journalistic value as they were posting directly what they were seeing. But this was before the era of deepfakes and AI. Now we have additional concerns about them being fake. But back in 2008 and till 2017, these issues were not a major concern.”

Siddhant Pratap, a Germany-based computer engineer says, “Deepfake and AI will make citizen journalism tricky as the tech is so advanced in 2024 that soon, professional tools will be needed to detect the use of AI in videos. Also, data rates are cheap in India as compared to the rest of the world. India also has the highest number of smartphone users. Some deepfake apps are already available for Android smartphones. This will make the fake news problem worse in future.”

India has a vast number of social media influencers, yet despite the country’s size, diversity, and myriad issues, there are very few influencers who intersect with citizen journalism.

Yawar Rashid, a Kashmir-based journalist says, “Content creation and citizen journalism are nearly absent in Kashmir due to the region’s complex issues and stringent laws. Kashmiris often compare their struggles to those in Palestine. The J&K Public Safety Act has instilled fear in the citizens, as even a simple Facebook ‘like’ on a post not aligned with the government’s views can result in imprisonment. Hence, content creation for awareness, reporting civic issues, and citizen journalism in Kashmir is still quite far-fetched.”

On the other hand, India has organisations like the People’s Archive of Rural India, which reports stories of 833 million rural Indians. But there are hardly any famous social media influencers who double down as citizen journalists.

“Dhruv Rathi (YouTuber) is one of the examples of a content creator who is doing a form of journalism called interpretative journalism, whether or not he calls himself a journalist or a citizen journalist," says Subramaniam.

Australian social media influencer and cook Tanzin—whose family survived the Bangladesh’s liberation war in 1971 and is now based in Sydney—says that kind of trauma trickles down through generations.

Born and raised in Australia, Tanzin, too, carries the generational trauma of her family. Her grandfather, Serajul Haque Khan, an intellectual, was among the three million people killed in the genocide. “I come from a family that has seen genocide first-hand. I grew up with my mother often talking about her trauma. She was 11 when she saw her father being taken away by the authorities. It was the last time she saw him. Seven months later, his remains were found in a pit.”

Tanzin, who has over 20,000 followers on Instagram, is vocal about Palestine and often attends protests in Sydney. “Apart from the trauma of genocide that I grew up with, I am a follower of Islam, so it is natural for me to be drawn to the cause of Palestine,” she shares.

“But there is no backlash from the government when we attend peaceful protests in Australia,” she says—a stark contrast to the treatment of Indian protestors showing solidarity with Palestine. Reports state that Indian protestors are often detained even for peaceful demonstrations in metro cities, with the latest instance involving dozens of protestors detained in Bengaluru.

Although Tanzin does not consider herself an activist, her influence and reach make her, and other influencers like her, significant voices against oppression. Content creators like her have stepped up, into roles that traditional media cannot fill.

77,000

The number of followers that photographer Ayman Al-Hassi has garnered after eight months of posting about the Gaza conflict on social media

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!