A unique research project is mapping the journeys undertaken by refugee European artists in the 20th century to six metropolitan destinations, including Bombay, where they lived, worked, exhibited and cooperated with local artists

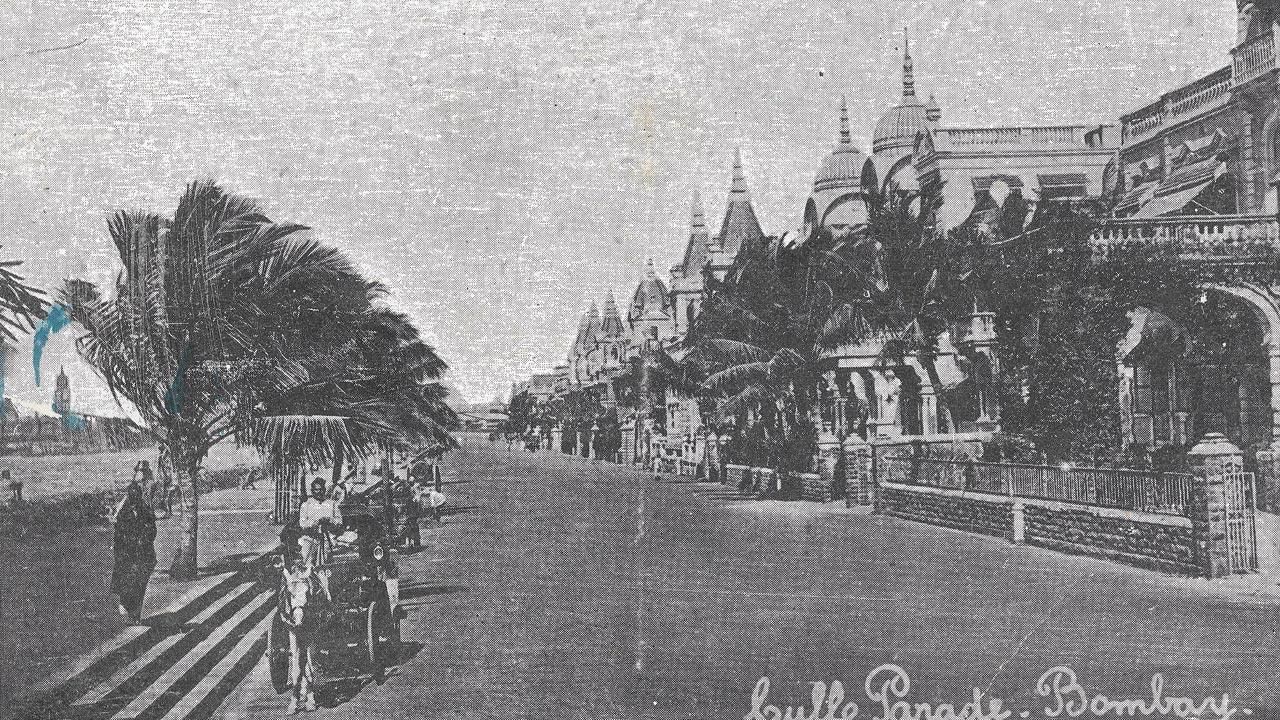

Postcard of Cuffe Parade, which was home to Jassim House, also known as Taraporewala Mansion, the former residence of several key figures of Bombay’s 1940s’ cultural scene. Pic courtesy/Private Collection Rachel Lee

When one discusses Modernism—the philosophical and art movement, which swept the West in the late 19th and early 20th centuries—the names of cities like Vienna, Paris, Berlin and London to some extent, are inadvertently mentioned in the same breath. But, a new research project, Relocating Modernism: Global Metropolises, Modern Art and Exile (METROMOD), which has been in the works for nearly four years, is attempting to tell the history of this movement from a more global perspective.

ADVERTISEMENT

“We wanted to get away from the notion that modernism was generated in these urban centres, and [instead], see it as a movement that developed through an exchange of ideas in different places, through the migration movements of exiled artists,” shares Rachel Lee, a postdoctoral researcher, who is currently based in Mumbai. Lee is part of a stellar team of researchers, who’ve been mapping the life and work of refugee European artists, between 1900 and 1950, when wars, dictatorships, violence and oppression forced thousands of artists to emigrate.

A virtual thematic walking tour, designed by Bureau Johannes Erler and Lab1100, which can be accessed on the website. The walk, which covers 7.45 miles, traces where these artists lived and worked, where they exhibited, and cooperated with local artists, and is sprinkled with audio clips, archival photos, paintings, and newspaper articles. Pic courtesy/Metromod

Six metropolitan destinations—New York, Buenos Aires, London, Istanbul, Bombay (now Mumbai) and Shanghai—where they sought refuge, are now the focus of the project. “We were looking at cities, where we knew there had been a considerable number of refugees, or where they had had a considerable impact, which was the case in Bombay, where despite being fewer in numbers, these exiled artists seemed to have been able to function quite well,” says Lee, over a Zoom call. Art historian Mareike Schwarz, who joined the METROMOD team last year, is focussing her research on Bombay. “These cities [also] witnessed a lot of trans-cultural exchanges between the exiles and the locals,” she adds.

Bombay became a friend like no other, embracing the bold ideas and values these artists represented. “I think there was this knowledge that independence [from the

British rule] was not very far off,” says Lee. This spirit of new beginning also brought along a willingness to experiment.

Magda Nachman’s costume design for Hilde Holger’s production of Baba Yaga, 1943. PIC COURTESY/Hilde Holger Archive © 2001 Primavera Boman-Behram. All rights reserved

Schwarz says, “Many people from the local creative scene were very open, and culturally interested. The knowledge which these exiled artists had cultivated elsewhere, was generally not met with suspicion, and was largely considered enriching. It led to a dialogue. That’s also why these creative developments took off.”

Among the most successful within the exiled artistic community were Walter Langhammer and Rudi von Leyden, both of whom were associated with the Times of India.

Rachel Lee. Pic courtesy/Amit Srivastava; (right) Mareike Schwarz

Langhammer and his wife Kaethe, whose Jewish background put the couple at risk in Nazi-occupied Austria, came to Bombay in 1938, after the former received an offer of employment as the newspaper’s art director, through a connection in Vienna. Among his many responsibilities were managing The Times of India Annual, an illustrated book published yearly in time for Christmas, where many of his paintings were also featured. Leyden, on the other hand, ran a Bombay advertising agency, which he closed down in the late 1930s, to take up a position in the advertising department of the newspaper. He later became its art critic, reviewing art exhibitions in the city under his initials RVL. “They didn’t have to earn a living from art [alone]. They had salaried jobs, and had a status in the city. If there was an art exhibition in the city, Rudi would be there. Langhammer was a secondary school art teacher and a talented painter, so he was committed to teaching art, but in an informal way, working with local artists. With his wife Kaethe, he also organised these salons that were opened to artists, to have meetings, talk about art or just to exhibit new works,” says Lee.

In comparison, Lee and Schwarz feel that women artists didn’t enjoy the same admiration, despite being equally accomplished and dedicated. Exiled painter Magda Nachman arrived in Bombay in 1936 to join her husband MPT Acharya, an Indian national, anarchist and communist. The couple lived in Malabar Hill. “Although Nachman was a teacher, exhibiting regularly at the annual Bombay Art Society exhibitions [she even won the Governor’s Prize in 1949 and received many commissions to paint portraits of moneyed families], she was always on the edge of financial despair. For some reason, she was not able to gain traction within the city’s [art] networks,” says Lee. Nachman found a friend in Hilde Holger, the exiled Viennese expressionist dancer and choreographer, who had speculated that the former didn’t receive support from the extended European community. Holger who lived at Queen’s Mansion near Azad Maidan, where she opened a dance school in 1941, experienced a similar struggle, as her art form didn’t seem to captivate Bombayites. That they were women, could have definitely proved to be an impediment, feels Lee.

Since the team started the METROMOD project, which is being helmed by its principal investigator Dr Burcu Dogramaci, professor of 20th Century and Contemporary Art History at the Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität Munich (LMU), they have been able to translate their work into varied mediums. Among the first was a book, Arrival Cities: Migrating Artists and New Metropolitan Topographies in the 20th Century, published last year, which included two chapters on Bombay. The most recent was a virtual thematic walking tour, designed by Bureau Johannes Erler and Lab1100, which can be accessed on the website (metromod.net). The walk, which covers 7.45 miles, traces where these artists lived and worked, where they exhibited, and cooperated with local artists, and is sprinkled with audio clips, archival photos, paintings, and newspaper articles. Jassim House, also known as Taraporewala Mansion, at 25 Cuffe Parade, and the Marine Drive sea-facing Art Deco building Soona Mahal, where exiled writer, critic and publisher Willy Haas, who fled Berlin via Prague, moved into in June 1939, are among the many mapped sites here.

Apart from a second collected volume, Urban Exile: Theories, Methods, Research Practices, which will release next year, the team is now working on another digital archive, comprising mainly images and texts, which will be published on the website in the next two months. “We will be mapping objects, persons, events and organisations to visualise the networks of artistic exile in the METROMOD cities. Besides presenting prominent exile protagonists in Bombay, the archive also wants to tell more or less forgotten stories. Our aim is to present an interactive map of all these entangled interactions that happened back then in Bombay,” says Schwarz.

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!