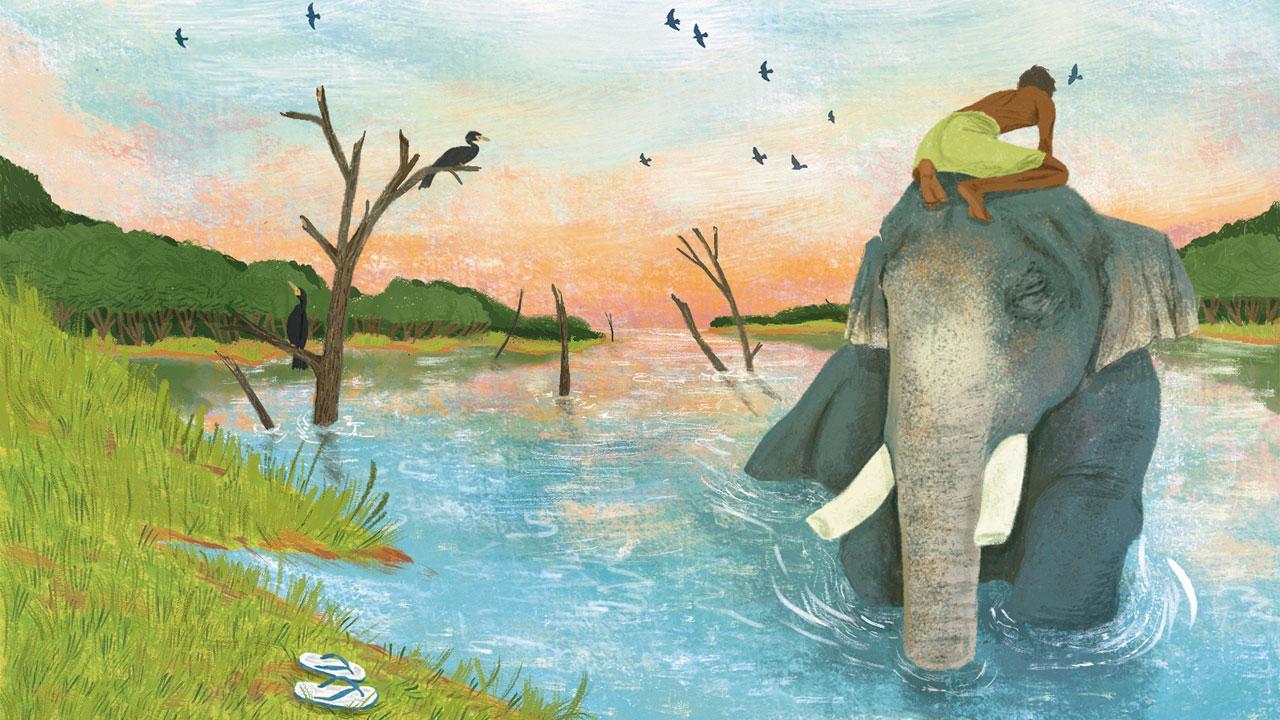

A new illustrated cookbook, documenting recipes from five communities of the southern state, makes a plea for recording what and how we eat

Interspersed with illustrations and recipes, the book offers an insight into Kerala’s cuisine, which is as diverse as its topography

From the Syrian Christian errachi olayathi, to the appam and stew of the Thiya community who were originally toddy tappers, to the puttu of the Nairs—a warrior community, to the idli and dosai of the Nambuthiris (Brahmins) and the delish biryani of the Mappilas—food in Kerala differs dramatically across regions, sects and castes. This variety is at the centre of writer and former Doordarshan broadcaster Sabita Radhakrishna’s beautifully illustrated cookbook Paachakam: Heritage Cuisine of Kerala (Roli Books, Rs 1,259). Her first was a compendium of all her mother’s recipes, and the second book was the award-winning Annapurni: Heritage Cuisine from Tamil Nadu (2015).

ADVERTISEMENT

A traditionalist at heart, it pains her to see all expressions of heritage—language, food, craft and textiles—languish. For 40 years, she has been working to revive language and textiles at the grassroots. Radhakrishna says she enjoys the process of producing a recipe book—from researching recipes to curating photographs, to designing and editing. “You must be patient through it. I think that documentation is very important for our culture—be it heritage, textiles, crafts, or foods. We’ve lost so much information that was passed down orally, especially because people kept so much of it secret for some reason. It struck me when I was trying to standardise my mother’s recipes. She would say, ‘use a bit of chilli powder’ or ‘just some tamarind’. So, I’d hold her hand and say, ‘tell me what is ‘this much’. And I would take it, measure it, and note it down,” she laughs.

During her research, she found out that Cochin has just five Jewish families left. By the time she decided to go there, Radhakrishna says there were none. She did manage to reach out to one of them settled in Mumbai. “Documentation is the answer,” she emphasises. “We’ve come a full circle, going back to the traditional in everything from haircare to skincare—looking for grandma’s secret in the kitchen. If there is no documentation, we wouldn’t have any record. So, I urge people who come across ancient recipes to please note them down for future generations.”

Sabita Radhakrishna

Kerala’s cuisine has a distinct identity. “It was an alien culture for me,” she adds, “so it made sense to reach out to people who’ve been working with traditional foods, picking out one expert from their community. What strikes me about Kerala is that the recipes are not diluted. They’ve been adhering to traditional methods and are orthodox about it.”

For the book’s research, Radhakrishna went into libraries looking for archival papers, found out the why and whereof a dish, why people use a certain spice or ingredient—even though she knew most of this research wouldn’t make it to the cookbook. “Maybe I am old-fashioned, but I don’t trust the Internet for authenticity,” she says. “Recipes online are often diluted with modern innovations. Instead, I took it directly from experts. Most didn’t know how to give measurements—they cook with andaz. So, I ended up deciphering their, ‘little this’ and ‘somewhat that’ by trying it out myself. I feel if you standardise the recipe, it turns out the exact way it was intended to.”

Kerala cooking has a certain distinct taste, a lot of which comes from the use of coconut, but also from the spices that grow in the state. “What’s amazing is that none of the flavours are overpowering—they always unravel on the palate in layers. You will feel the pepper and the chillies first, and if there’s coconut milk, it sort of subdues the taste. Despite the influence of the Portuguese and Arabs, it’s still quintessentially Kerala. Even the beautiful cakes baked there are largely learnt from the West, but they carry the Kerala trademark.”

Meen porichathu

Ingredients

1 kg seer fish, cleaned

4 tsp red chilli powder

3/4 tsp turmeric powder

4 tsp vinegar (red or white

1 marble-sized ball of tamarind. Soak in water for 30 minutes and extract juice

3 tbsp + 1 tsp coconut oil

Salt to taste

Method

Make a few vertical gashes (2–3 inches) on both sides of the fish. In a small bowl, stir together the chilli powder, salt, turmeric powder, vinegar, and tamarind juice. Smear the paste on both sides of the fish. Let rest for 30 minutes. Heat the coconut oil in a tawa over medium heat. Add the fish. Fry on both sides until dry and golden brown. Serve hot with steamed rice and parotta.

Mahashais

Ingredients

1.5 kg large to medium-size onions

1 kg minced lamb, beef or chicken

12 garlic cloves, finely chopped

1 inch fresh ginger, peeled and finely chopped

1 dried red chilli, thinly sliced

1 green chilli, thinly sliced

1 large bunch fresh coriander, chopped

1 tsp turmeric powder

1 tsp red chilli powder

1 tbsp raw basmati rice

Salt as needed

1 cup malt vinegar

250 gm palm sugar

Coconut oil for frying

Method

Preheat the oven to 170°C. Using a sharp knife, slice from the top of the onion, as though you are cutting it in half, but do not cut all the way through. This will help each layer hold shape. Peel each layer carefully. Do not make haste, or the skin will tear.

Wash the minced meat and place it in a bowl. Add garlic, ginger, dried red chilli, green chilli, coriander, turmeric powder, chilli powder, rice and salt. Mix thoroughly. Take an onion layer in your hand, and slide your finger under the first ring. It should come away easily. Take one tablespoon of the minced meat mixture in your hand and make an oval shape. Wrap the onion leaf around the mince. It will hold well. Do not overfill the peel. Continue with the remaining peels and meat mixture.

Heat four tablespoons of oil in a large skillet on medium heat. Working in batches, gently add the mahashais to the hot oil in a single layer. Fry for about five minutes or until golden brown. Carefully turn to brown on all sides. Transfer the mahashais to an oven-proof dish. Fry all the mahashais and keep aside. In a small bowl, whisk vinegar and sugar together. Season with salt. Pour this sauce over the mahashais. Cover the dish with aluminum foil and bake for 30 minutes. Remove the foil at the last 10 minutes of baking.

Note: Use well-shaped onions that don’t hold two bulbs.

Radhakrishna’s favourites

Nairs: Mambazham puliserry is a lovely blend of sour yoghurt and the sour-sweet mango.

North Malabar Thiyas: Neyyi choru or simple ghee rice is subtle, and goes great with chutneys and curries.

Moplahs: Thalaserry biriyani is a complicated recipe, but taste-wise, light and not heavily spiced.

Poduvals: They have strictly vegetarian dishes that are light on the stomach but the uli thiyal is a tamarind-based curry with spice and a shot of tamarind, fried shallots, and of course, coconut fried to a rich brown.

Cochin Jews: Mahashais is an unusual, delectable dish made by peeling the onion layer by layer, packing each leaf with spiced minced beef or mutton, and sauteing them.

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!