In an exclusive walkthrough of art gallery Tarq’s new Fort address—before it opens to the public this week with a show by Sameer Kulavoor—mid-day finds the interiors as fascinating as the works on display

In his new series, artist Sameer Kulavoor experiments with reverse paintings on acrylic sheets and large compositions of drawn timelapses that could play out like an animation in a flip book. While there’s still his notable style of observing the city around him, over the years, his work delves more into its structures and details. Pics/Shadab Khan

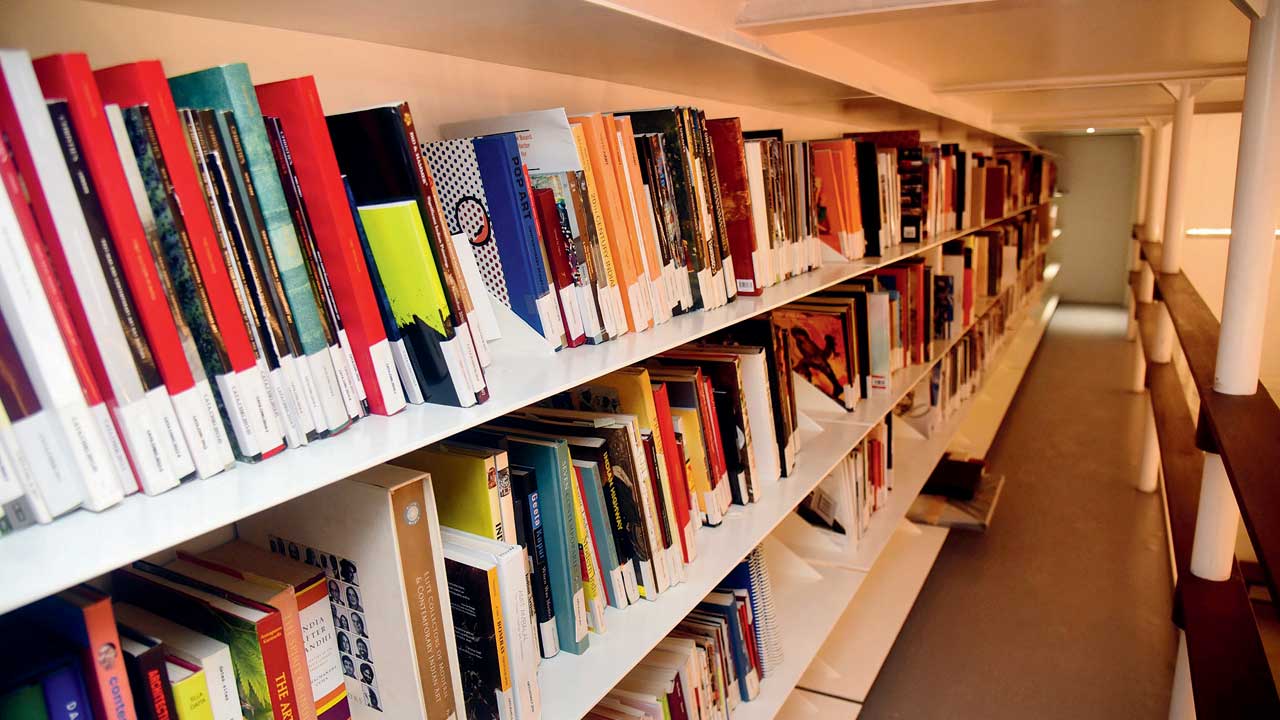

"The beginnings of these works take off from my last show, You Are All Caught Up, which was on display three years ago at the old address,” explains Mumbai-based artist Sameer Kulavoor as we walk into Tarq’s new space at KK Chambers in Fort that’s exhibiting his latest series of art. Housed earlier in a distinct art deco building within the verdant complex of Dhanraj Mahal in Colaba, the gallery has moved into this new, more contemporary-styled space in a 100-year-old brick-face structure which has cleaner lines, taller ceilings and starker interiors… at first glance. A closer look, however, reveals the tiniest but remarkably unique designed details.

“We unknowingly outgrew it sometime during the pandemic,” points out founder and director, Hena Kapadia, as we take in the expansive interiors, “mostly for practical reasons such as requiring more space, not just for storing our art, but with more scale and volume for showcasing it like we have here.” As chance would have it, her close professional and personal ties with artist Vishwa Shroff (whose works are showcased at the gallery) and her husband, Japanese architect Katsushi Goto (who both co-own Square Works Laboratory housed a few floors above), led Kapadia to this location after hunting around for a few months. And she began to work with Goto on restoring and designing the new gallery.

Described as initially looking like an excavation site, the entire place was in complete disrepair after being untouched for over 15 years. “I did want to tie the new gallery back to Dhanraj Mahal in some way because it always felt very warm and welcoming,” says Kapadia. “It also needed to feel like a happy space where people would be comfortable to come and talk to us—whether they’re students, artists, collectors or folk interested in knowing more about art.” And a large part of this warmth could be chalked down to the abundance of teak—from the floors to the furniture—found across the earlier space.

“In terms of materiality, we immediately agreed that we’d have to incorporate elements of teak here as well,” says Goto. “While most of the art deco-style furniture was going to be repurposed, Hena also wanted to express a new chapter, so you’ll also find a bit of an industrial touch.” He shows us around what looks like a far more utilitarian space. “This premise occupies a corner of the building which faces the north-west, and has less than a handful of windows open to natural light,” he says of the section of the gallery that displays the art. “So, it only made sense to design the viewing space here.”

Architect Katsushi Goto has designed Tarq’s gallery as a more expansive space with tiny but remarkably unique details

Architect Katsushi Goto has designed Tarq’s gallery as a more expansive space with tiny but remarkably unique details

Oddly enough, the two main windows are housed within an arch, fitted deep inside an alcove in the wall. In a departure from conventional design, the hinges rest vertically along the centre of the frame, closing both panes on each side. Simple brass knobs shaped like flat nails without threads (which we initially thought were light dimmers), slide out to lock each window in place. “The head is a little off-centre to allow it to screw on tightly on one side,” adds Goto. Similarly, the same teak forms thick lines of grouting between the concrete floor, and talls panels of it have been fitted outside the recesses of each H column along the room to make them look more uniform, in terms of shape and aesthetic, and to also cleverly conceal wires and electric sockets. “If you pop open one of the squares at the bottom, you can plug in any device—even in the middle of the room! Goodbye messy wires!” he chuckles. A long continuous length of strip lights, by lighting designer Tripti Sahani, seemingly float under the ceiling along the perimeter of the room echoing a single line drawing.

Of choosing Kulavoor’s works to open the new gallery, Kapadia says, “Sameer was the first person who came to mind mostly because of the scale of his art, which will elevate the volume of this space.” In his new series, Kulavoor experiments with reverse paintings on acrylic sheets and large compositions of drawn timelapses that could play out like an animation in a flip book. While there’s still his notable style of observing the city around him, over the years, his work delves more into its structures and details. “I think this switch happened some time between the two lockdowns, where I started focusing on architectural elements more than the human form…and continued to pursue them because they grew more and more interesting. At the same time, my father was building a house in Mangalore—that I was also involved with—which got me to play around with themes of what happened in India post independence with modernism and postmodernism,” he recalls.

Hena Kapadia

Hena Kapadia

While people seem hidden in the background in this body of work, Kulavoor also notes that looking more intricately at architecture gives us an insight into human language, where the smallest details can betray the political climate, social or economic hierarchies, and triggers in a society. “Take a simple chhajja, for example,” he illustrates, “it may not be a part of a structure’s original design, but it can reveal a lot about the occupants who built it if it hasn’t been repaired in ages, if it’s a simple or overly ornate design, if it’s taken off overnight revealing new occupants…and even places that don’t need one displaying the luxury of good design!”

Referring to the title of the show, Edifice Complex, Kulavoor explains how it was a phrase coined by Filipino activist Behn Cervantes during the autocratic reign of Ferdinand Marcos, president of the Philippines from 1965 to 1986. “The Marcos administration was on a spree of building grandiose structures to portray an impression of progress and power,” he explains. “In the last five to eight years, I’ve been seeing structures like this all over India. There’s a very brazen way of building certain elements in architecture that may not necessarily have any logic. And, at the same time, I was reminded of the Memphis Movement which rejected Bauhaus styles of strict, straight lines of modernism, bringing in elements of being free. Ironically, the founder, Ettore Sottsass, visited India in the ’60s and ’70s, and was inspired by the architecture of post-independent India. In the west, however, they build in a playful way out of privilege—here it’s because we may not have the resources to get an architect on board for sound design.”

Edifice Complex is on view at Tarq, KK Chambers, Dr Dadabhai Naoroji Road, Azad Maidan, Fort, Mumbai, from April 14 to June 10

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!