A grassland restoration project in Pune district promises to save both, the indigenous Dhangar shepherding community and the genetically vital gray wolf

A Pallid harrier seen flying above the grasslands in Kendur. It’s the lack of specific policies to protect the grasslands, a vital biome, that has excluded it from mainstream conservation. Pics/Pradeep Dhivar

In 2008-09, Mihir Godbole had an epiphany: He needed to do more than take stunning pictures of the savannah grasslands surrounding Pune to conserve them. Considered wastelands, these are home to the endangered Indian gray wolf and black buck, among other species of wild animals. Providing high-quality grass for domesticated animals, this effort also has the potential to significantly improve the livelihoods of neighbouring villages.

In 2019, Goldbole founded The Grasslands Trust. Two years later, his trust collaborated with the Ashoka Trust for Research in Ecology and Environment (ATREE) for a pilot project to recover the grasslands in Kendur village of Shirur taluka in Pune district.

Feral dogs in the area have turned into competition for the wolves, chasing and hunting chinkaras, which will disturb prey-predator dynamics

Feral dogs in the area have turned into competition for the wolves, chasing and hunting chinkaras, which will disturb prey-predator dynamics

Experts say that the lack of specific policies to protect this biome has led to the exclusion of savannah habitats from mainstream conservation. Large tracts all over India are under tremendous pressure from anthropogenic developmental activities. Overgrazing by domestic cattle and frequent fires have gradually exterminated nutritious grass species. Non-nutritious grasses have taken over, rendering vast tracts unpalatable to herbivores—domesticated and wild—threatening the survival of the blackbuck and Indian gazelle. This has increased crop raiding, and carnivores in the region are depending more on livestock and carcasses due to decrease in natural prey. Random and unscientific plantation activity is further escalating habitat modification and degradation.

Considering all these factors, Godbole, founder-president of The Grassland Trust, and a team of like-minded conservationists knew it was critical to generate awareness about the savannah ecosystem and implement scientifically sound restoration measures to revive and conserve them.

(From left) The Grassland Trust team along with the villagers of Kendur: Ganesh Thite, Saurabh Thite, Shreyas Nakate, founder-president Mihir Godbole, Vijayraj Jare, Suryakant Thite and Popat Jagtap

(From left) The Grassland Trust team along with the villagers of Kendur: Ganesh Thite, Saurabh Thite, Shreyas Nakate, founder-president Mihir Godbole, Vijayraj Jare, Suryakant Thite and Popat Jagtap

After baseline studies and surveys, The Grasslands Trust got in touch with the villagers of Kendur, located about 50 km away from Pune. “We have been assessing the biodiversity of the open natural ecosystems in Pune district since 2012,” says Godbole, “and discovered that they are the perfect breeding ground for the Indian gray wolf and striped hyena. A good population of Indian gazelle or the chinkara can also be found there, in addition to other elusive species such Bengal foxes and Indian crested porcupines. Most species of birds, amphibians and reptiles thrive only in this habitat, and many such vital sites come under the Forest department’s jurisdiction.”

Before implementing the pilot project, awareness sessions were conducted to increase public understanding of the importance of these ecosystems, their biodiversity and the benefits of sustainable land management practices. When restoration work began, they found no protocol detailing grass species as no one had worked extensively on such an endeavour in the Deccan plateau.

Shreyas Nakate, research assistant

Shreyas Nakate, research assistant

“ATREE-Bengaluru played a very important role as they have been working on restoration and wildlife ecology research for 25 years. We got protocols from them and some individual scientists,” says Godbole. “Based on these, we conducted flora, fauna and soil testing and surveys, and 10 plots from the landmass at Kendur were selected. On the suggestion of retired conservator of Forest Subhash Badave, we planted five grass species, colloquially called paunya, sheda, dhaman, anjan and dongri.” Their Latin names are dicanthium, sehima sulcata, sehima nervosum, apluda mutica, themeda, aristida, cenchrus, and chrysopogon.

Regeneration will be undertaken on minimal land and in minimal density because once the grasses grow, their seeds will disperse naturally and spread. A 10-hectare plot has been demarcated on a 500-hectare wide plateau, and villagers have agreed to keep it grazing-free for some time, and even guard it from fires. Eventually, this human-wildlife win-win situation will transform the lives of 8,000 villagers, and 4,700 hectares of land.

The Dhangars or shepherd community will be one of those to benefit directly from this project. They will rely on the cut-and-carry method to feed their herds until the grass saplings proliferate

The Dhangars or shepherd community will be one of those to benefit directly from this project. They will rely on the cut-and-carry method to feed their herds until the grass saplings proliferate

Jare said 15,000-20,000 grasses were planted in the trenches on the plateau. A nursery was nurtured at Fergusson College in Pune to cultivate the diverse native grass species that could be transplanted to the pilot site, and provided 7,000-8,000 saplings “The forest nursery from Nashik gave us 10,000 saplings,” he continues, “and an agricultural college from Ahmednagar donated the remaining.” The state Forest department is cognisant of the restoration effort, and hopes to implement it in other grassland areas under its jurisdiction in the coming year. As we walk through Kendur with Godbole and his team, the sarpanch and other villagers join us and are pleased that despite less rainfall, many of the saplings have thrived.

ATREE’s Dr Abi T Vanak, Anuja Malhotra and Iravati Majgaonkar designed the project, its training modules and policy brief to make it sustainable for policymakers. The on-ground implementation was led by Grasslands Trust’s Makarand Datar, Prerana Sethiya, Nikita Sabnis, Shreyas Nakate and team members. Vijaraj Jare facilitated the engagement of villagers in the project.

Ganesh Rajaram Tithe, Kendur villager

Ganesh Rajaram Tithe, Kendur villager

Discussions with the local agrarian community offer us insights into their requirement for fodder for livestock, and ideas for innovative restoration interventions. As we climb to the restoration site, the sarpanch is optimistic this will benefit a majority of villagers who depend on milk production and farming for livelihood.

“Earlier,” says Suryakant Thite, “wild grass covered the hill. Livestock farmers noticed our cows, buffaloes, and goats were not getting enough grass to eat, or avoided eating some varieties. We decided to work together as the success of the project would benefit us as well.”

The Dhangars or shepherd community, one of those to benefit directly, are relying on the cut-and-carry method to feed their herds until the grass saplings proliferate. Popat Vitthal Jagtap, a villager who helps protect the hill says that the project will also generate jobs during plantation months. Jare says at least 20 villagers will be employed on a daily basis for three months.

(From left) Grass varieties such as dicanthium, dehima sulcata, etc. Their intricate root structures draw in and store both water and carbon into the oil ; Despite less rainfall, the villagers and project managers are glad that the saplings have thrived; The Indian gray wolf is classified under Schedule I of the Wildlife Protection Act (1972) and is considered an Evolutionary Significant Unit. Pics/The grassland trust

(From left) Grass varieties such as dicanthium, dehima sulcata, etc. Their intricate root structures draw in and store both water and carbon into the oil ; Despite less rainfall, the villagers and project managers are glad that the saplings have thrived; The Indian gray wolf is classified under Schedule I of the Wildlife Protection Act (1972) and is considered an Evolutionary Significant Unit. Pics/The grassland trust

Jagtap’s neighbour, Ganesh Rajaram Tithe, admitted being unconvinced at first, but when he understood the long-term gains, he became instrumental in getting others on board. “Like this plateau, we have another huge chunk of land on another plateau,” he says, “and I want the Trust to replant it too. A majority of the people in our village are into small-scale milk production. We don’t have too many other employment opportunities; factories are 15 to 20 km away. If the right kind of grass increases milk production, we will be able to save the money we use to buy fodder in summer.” Saurab Popat is also looking forward to saving the money that goes towards purchasing fodder in the months that grass does not grow.

Another gain to the farming sector will be the raising of the water table in the region, enhancing groundwater recharge. “Grasslands are natural sponges, absorbing rainfall and reducing runoff, which helps prevent soil erosion and allows water to seep into the ground,” says Jare. “Their elaborate and wide-spread root systems improve soil structure and retain water, and by covering the soil, they reduce water loss through evaporation.”

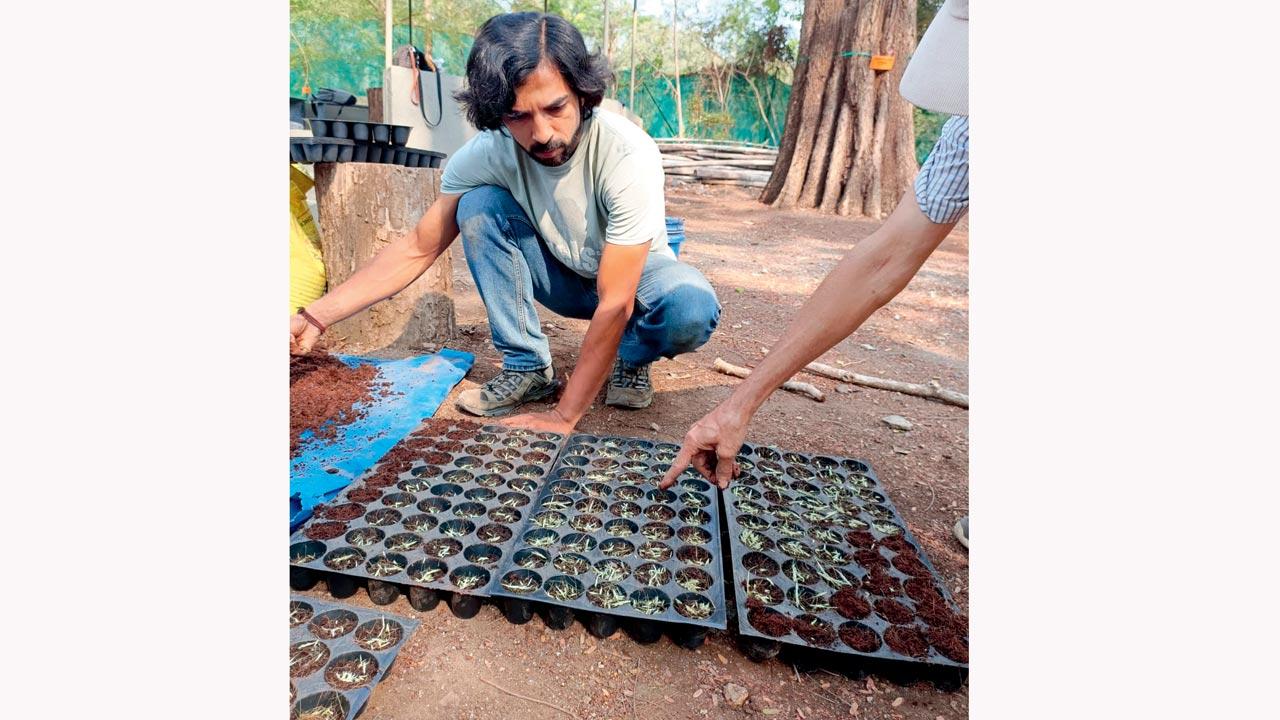

Palatable and nutritious species of grass such as paunya, sheda, and dhaman were transplanted from nurseries around the state to Kendur

Palatable and nutritious species of grass such as paunya, sheda, and dhaman were transplanted from nurseries around the state to Kendur

Then there’s the vital role that grassland restoration can play in carbon sequestration and mitigation of climate change. “They are reliable carbon sinks; the deep root systems can store significant amounts of the gas in the soil,” says Godbole. “They also improve ecosystem resilience, enhancing the ability to adapt to climate

change impacts.”

This is also an opportunity to closely study the important indigenous species of the ecosystem, most crucially, the Indian gray wolf which is considered to be a million years older than any other wolf species in the world. It is classified under Schedule I of the Wildlife Protection Act (1972), and given its unique place in evolutionary history, the species is considered Evolutionary Significant Units (ESUs). An ESU is a population or group of populations that is reproductively isolated from other population units of the species, and thus, represents an important component in the evolutionary legacy of the species. Around 3,000 gray wolves remain in the wild, the same population as tigers (2,967).

The Trust’s team, led by wildlife researcher Adwait Deshapande, is using drone and AI technology to monitor resident packs. Deshpande is specialising in studying animal behaviour at the Max Planck University in Germany. Under the project The Collective Behaviour of Indian Wolves undertaken in Pune district, they are studying movement patterns of packs, communication between members and other species, and also assessing whether individual identification of wolves is possible.

Research assistant Shreyas Nakate, who holds an MSc degree in biodiversity, says, “We tracked a pack of wolves from February till August-September from a height of 40 metres with thermal drones. We observed that the home range of pups increases as they grow. The video was taken from a 90-degree angle so that we could observe whether the coats of individual wolves differ in pattern and colour gradation, and can be used as differentiation markers.” What this essentially means is to see if wolves recognise each other based on what they are wearing.

This project also endeavours to understand why the wolves are a unique species. “Gray wolves are an endangered species from a threatened ecosystem, so this project is going to be of huge significance to plan better conservation strategies for this charismatic animal,” says Nakate.

The pilot project was undertaken in February at Baramati with two to three packs of wolves. One pack, with a larger number, was tracked for almost two months. The research team would rest only between midnight and 5.30 am, and spring back on the field in the inhospitable landscape. The team wondered about the night life of the species, and found that post sunset, they cover a vast territory, making it challenging for the team to track them. They rest most of the day. The pack was recorded hunting down chinkaras, civets and an Indian hare, also known as the black-naped hare. “This wolf is an apex predator of the grasslands, and a keystone species,” informs Nakate, “When we conserve it, other species of the grasslands, such as the chinkara [Schedule 1], foxes, jackals, hyenas and lesser mammals such as civets will also be protected.”

During mid-day’s visit to Kendur and the adjoining area’s landscape, we noticed packs of feral dogs. “These have become direct competition to wolves,” says Nakhate, “We have footage showing them chasing and hunting chinkaras, which will imbalance the prey-predator dynamics. They are also a menace to human settlements, as they attack sheep, goats and even cattle. They also carry dangerous diseases, such as the canine distemper virus, which poses a huge threat to already endangered species.”

A devoted team, including key members such as Prerana Sethiya, who is a data analyst and lead strategist at the Grasslands Trust, and Nikita Sabnis, who is in charge of data administration and report development, have contributed significantly to the grassland restoration project. Mugdha Edake, Sai Bhurke, and Nidhi Joshi have also been involved in the restoration project. Aarnav Gandhe also worked as a research assistant for the drone project from University of Konstanz is also an important collaborator in the project.

2-3K

Gray wolf population

Why grasslands rock

. Reliable carbon sinks

. Improve ecosystem resilience

. Recharge groundwater table

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!