In their new collaboration, Julia Hauser and Sarnath Banerjee take you to colonial times where as the plague raged, morality was shaped. He wants you to come along for the ride; she wants you to never forget

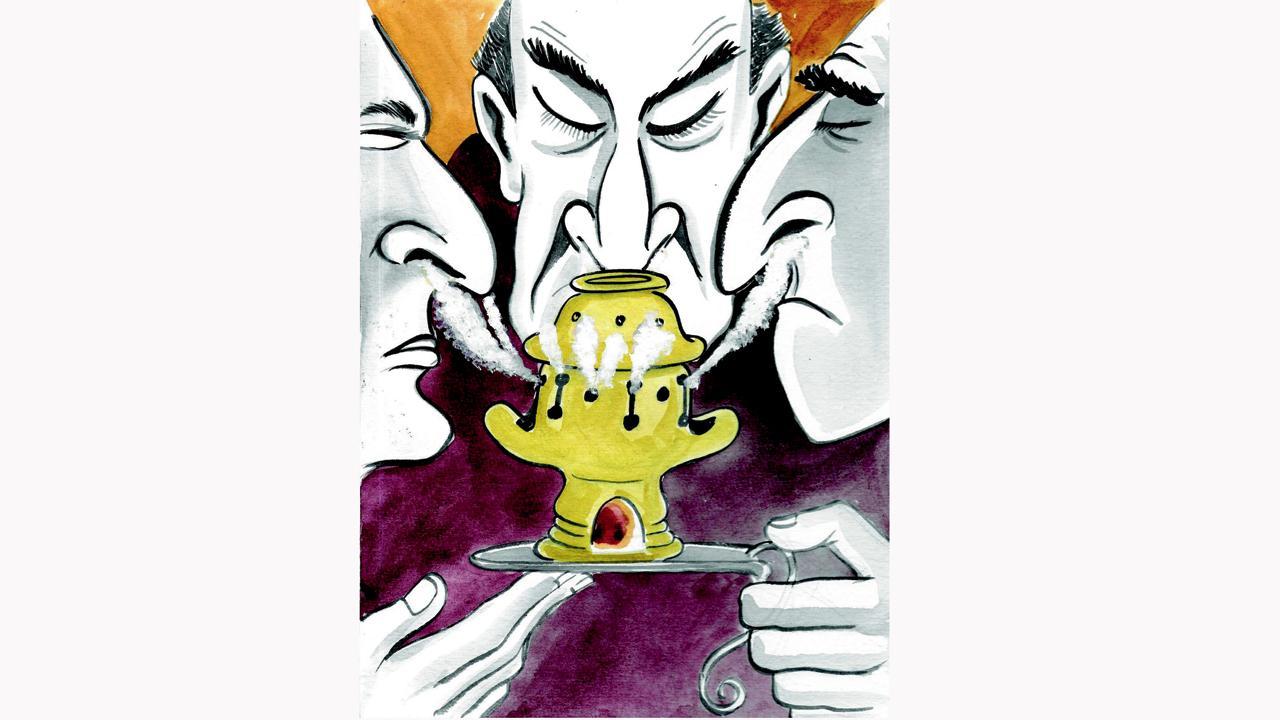

Like steam inhalation became commonplace during the Coronavirus pandemic, the book says that when the plague was raging in Europe, people were advised by writers like John of Burgundy to “burn juniper in their fireplaces or inhale fragrant powder heated over a fire of coals”.

Like there was COVID, there was once the bubonic plague. And not just any plague, but one that lasted from the 1300s to the 1900s, a wave arriving every few years, and leaving behind a trail of deaths. The first big European outbreak was in the 14th century, and then in 1665, a new wave hit St Giles outside London. It was in 2020, as we grappled with a new normal when the first wave of the Coronavirus pandemic swept India and the world, that lecturer Julia Hauser, who teaches modern history at the University of Kassel in Germany, wondered about the similarities between the plague and the modern pandemic. “All the libraries were shut, so I started reading information online, and dug up Internet archives. I then reached out to people who may know more,” says Hauser over a phone call from Germany.

ADVERTISEMENT

Three years later, this curiosity has given shape to The Moral Contagion (HarperCollins), where Hauser combines intensive research with imaginative storytelling and Sarnath Banerjee helps her create a graphic narrative.

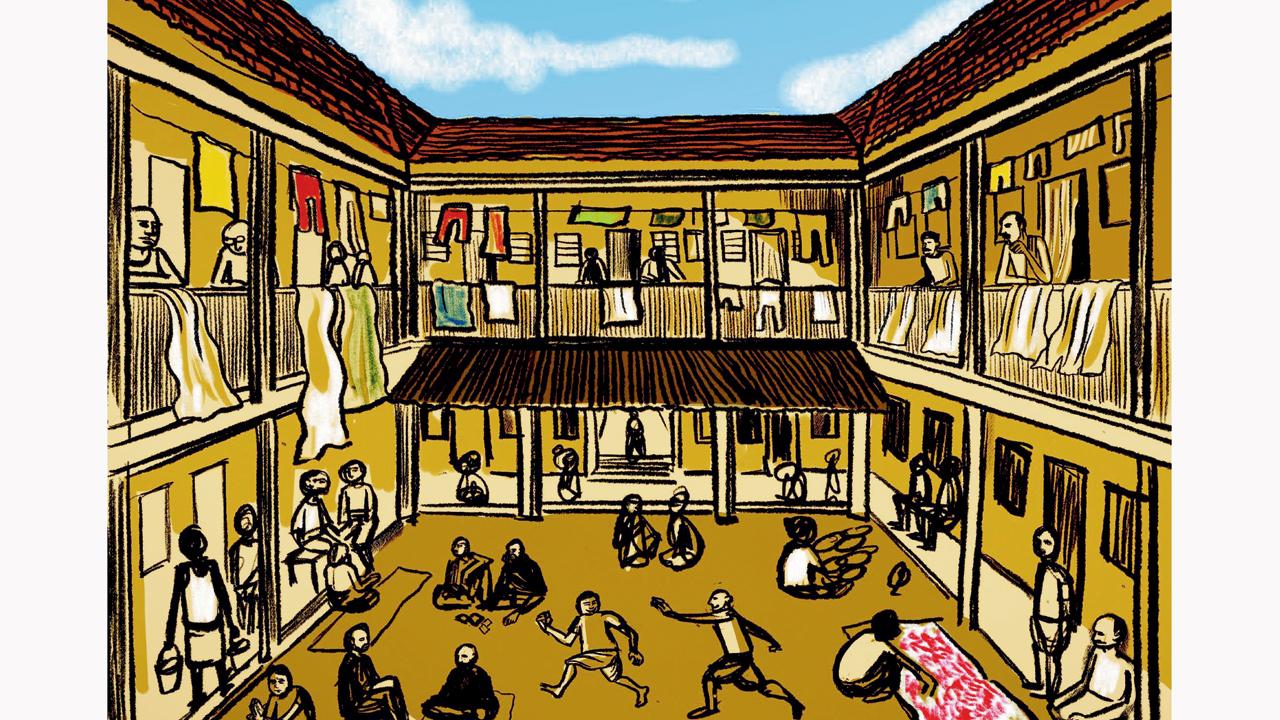

Julia Hauser writes in the book that the plague in Mumbai first broke in the crammed chawls of Mandvi where close to 30 persons lived in a room and the lower floor was used to stock grain frequented by rats. “As elsewhere, the plague wreaked the greatest havoc among working-class people. Often undernourished and chronically exhausted, they could not afford to stop working when ill.”

Julia Hauser writes in the book that the plague in Mumbai first broke in the crammed chawls of Mandvi where close to 30 persons lived in a room and the lower floor was used to stock grain frequented by rats. “As elsewhere, the plague wreaked the greatest havoc among working-class people. Often undernourished and chronically exhausted, they could not afford to stop working when ill.”

In the Moral Contagion, the reader journeys through Istanbul where the disease was so new that healers were stumped, to Florence where streets were stacked with rotting corpses, and sex and hot baths were banned, to London, where a few members of the elite class continued to live it up, to India, where the pandemic played leveller. Understandably, Hauser had much to sift through. “In Italy, a bunch of friends left the city and encountered many horrors—where people had been left in their homes to die. In North Africa, entire villages were deserted… all this was shocking to me,” says the author of An Entangled History of Vegetarianism. Banerjee though, was interested in the morality aspect. “It was a time when the seeds of conservatism were spreading—the church got stronger, prostitutes were driven out, homosexuality was barred, and the privileged could sequester at home. Such instances were detailed in The Decameron written by Giovanni Boccaccio in 1353. He recounts the horrors of the plague in Europe as he and his friends leave the city. It wasn’t very different from stories of south Mumbai’s elite residents who packed their bags and moved to Alibaug during COVID. I realised that in the Western world, the idea of morality was built around the plague,” says the illustrator. London was empty, most shops shuttered, the nobles moved to the countryside and the King had moved to Salisbury.

Like the containment zones India’s mega metros saw spring up where a cluster of Coronavirus infections emerged, London too experimented with strict quarantine. Red crosses on doors indicated the presence of a patient and flouting rules invited a death sentence; Mumbaikars had the BMC’s infection notice pasted on our doors.

Mehtab, the daughter of a rich Parsi textile mill owner in Bombay of the late 1800s was opposed to inoculation, much like the anti-vaccine brigade that cropped up during the COVID-19 pandemic. A member of the Bombay Theosophical Lodge, she roamed the streets distributing information against the vaccine and instead supported natural therapy and homeopathy. Illustrations/Sarnath Banerjee, The Moral Contagion

Mehtab, the daughter of a rich Parsi textile mill owner in Bombay of the late 1800s was opposed to inoculation, much like the anti-vaccine brigade that cropped up during the COVID-19 pandemic. A member of the Bombay Theosophical Lodge, she roamed the streets distributing information against the vaccine and instead supported natural therapy and homeopathy. Illustrations/Sarnath Banerjee, The Moral Contagion

In one of the chapters, Hauser says poignantly, that most people became “immune to grief”—a phenomenon we experienced as the pandemic progressed too. “The bubonic plague went on for centuries and people learned to live with it. Some even thrived during it, like 17th-century British naval administrator in London, Samuel Pepys, who recorded his life in the 1660s in a diary and amassed riches and lovers.”

Hauser speaks of another similarity between the Great Plague and the Coronavirus pandemic: the targeting of minorities, whether religious, sexual or ethical. “In colonial times, their homes were torn down—the dynamics of power changed since everyone tried to come to grips with the situation,” says Hauser. Much like in Indian metros, in then Bombay, hospitals were overrun with the rich and poor alike. “It’s like the fresco of the skeleton taking people to the death of dance—he doesn’t discriminate.” Banerjee feels that the main difference was that during COVID, the display of courage and love were in plenty.

Julia Hauser and Sarnath Banerjee

Julia Hauser and Sarnath Banerjee

In February 1666, London was declared safe and the King and his court returned. Life was limping back to normal.

Hauser hopes that the reader can observe themselves dispassionately the next time a big change takes us by surprise. “I hope we don’t target a certain section of people, and heed the scientists. I hope we remember lessons learnt the next time around, because this has not ended.” Banerjee on the other hand, says wryly, that he doesn’t care what people think of his writing. “I don’t think it’s a book about history repeating itself. I think it’s a romp through global history—from Bombay to South Africa, to Hong Kong. And as I drew the characters, I became a part of them. There was this strange apnapan, a sense of belonging.”

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!