A fairy-tale romance with an African-American jazz sensation, surviving a murder attempt, an epic escape from the jaws of death at a Japanese labour camp during World War II—all this after being part of India’s inaugural cricket Test match at the Lord’s Cricket Ground in 1932, whose 90th anniversary we celebrate this week

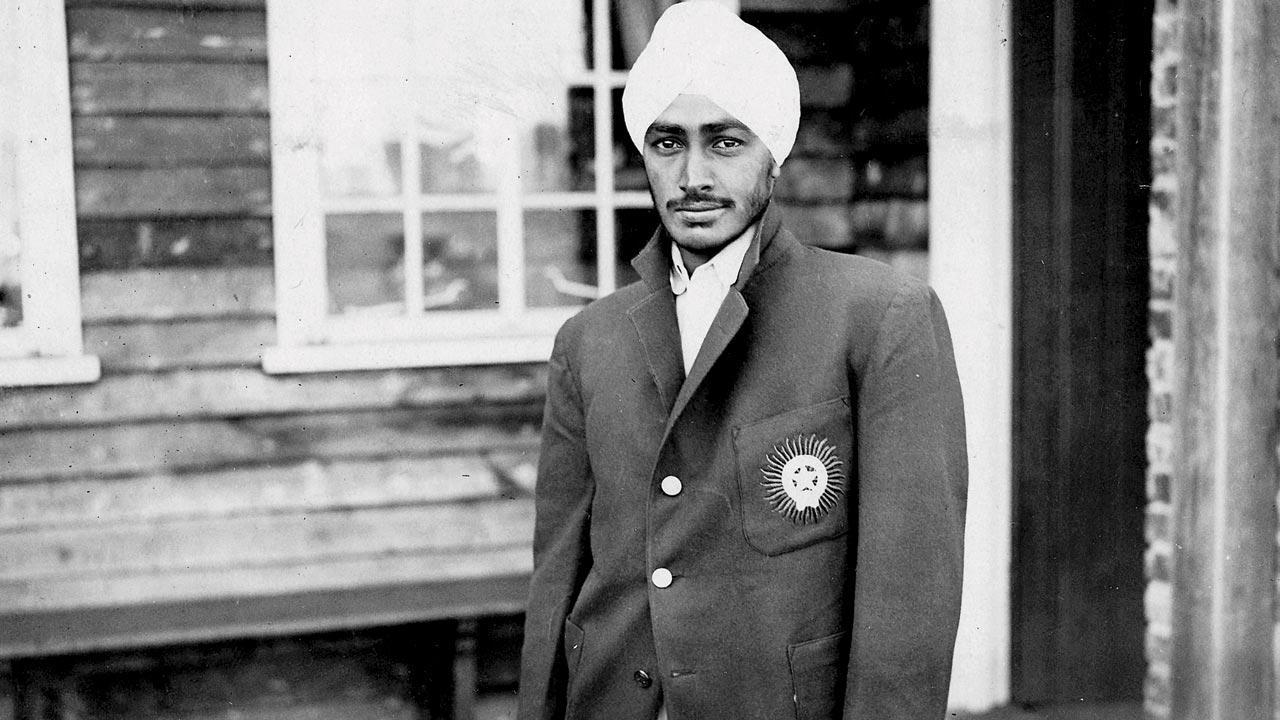

Lall Singh on India’s 1932 cricket tour of England. Pic/Getty Images

What do they know of cricket who only cricket know?

– CLR James

It all started with a chance meeting with British-Malaysian Ian Syer, the co-founder of Beijing’s buzzing burger joint cum bustling bistro, Plan B, and the long-time president of the Beijing Cricket Club, in 2016. One fine afternoon, while manning the bar counter and having introductory chitter-chatter, cricket-crazy Syer casually told me, “You know my mother’s uncle had played Test cricket for India.” Replying to an inquisitive mind’s spontaneous, “Who?” the Beijinger, who is married to a Chinese, nonchalantly remarked, “We used to call him Lall uncle…Lall Singh Gill.” A flabbergasted me instantly reacted, “WTF!”

Tariq Shamsi, whose father married Lall Singh’s niece

Tariq Shamsi, whose father married Lall Singh’s niece

Of course, like many cricket history aficionados and pundits, I had always found the first ‘Turbanator’ of Indian cricket, who stole some thunder in India’s maiden Test match at Lord’s in 1932, an enigma. Singh’s was always a partially-solved mystery.

Arguably one of the pioneering utility players for India, Singh had scored 15 and 29 respectively in the landmark Test (whose 90th anniversary we celebrate from June 25) and took one catch in his side’s historic debut before putting together a quickfire 74-run partnership with Amar Singh in just 40 minutes while fighting for a losing cause in the second innings of the Test that was eventually won by Douglas Jardine’s formidable side by 158 runs. But the turban-clad 22-year-old’s magnificent fielding to run Frank Woolley out in the opening hour remained one of the earliest highlights of India’s impressive initiation into Test cricket. In his seminal work of History of Indian Cricket, author Edward Docker described Singh’s sensational manoeuvring at mid-on: “The Sikh was an extraordinary quick mover, who glided over the ground like a snake, and his pick-up and return to ’keeper Navle [Janardan] just beat Woolley home—19-3.”

Jazz singer Myrtle Watkins (later known by her stage name Paquita), who Lall Singh had an affair with. Pic courtesy/Personal collection of Tariq Shamsi

Jazz singer Myrtle Watkins (later known by her stage name Paquita), who Lall Singh had an affair with. Pic courtesy/Personal collection of Tariq Shamsi

However, after playing just that solitary Test at Lord’s, the man with a nimble pair of legs and safe pair of hands went into oblivion faster than his sudden landing in the Indian cricket virtually from nowhere. With the hope of playing India’s first-ever Test on the Indian soil, Singh returned to India in October 1933 “at his own expense,” but tragedy, as it turned out later, was synonymous with the exuberant cricketer’s life. “He was unfortunately not qualified to play for India under the existing Test rules, as he cannot claim either birth or residential qualification. When he was in England last year as a member of the Indian team the Imperial Cricket Conference granted a special sanction for him to play for India in the one Test match on the condition that this was not to be regarded as a precedent,” The Bombay Chronicle reported.

There began both the misery as well as the mystery of the man who was once dubbed by the media as one of the best fielders in the world. A discarded Singh literally faded into oblivion. Richard Cashman wrote in his book Patrons, Players and the Crowd that Singh ran a nightclub in Paris with his wife. In his magnum opus, A History of Indian Cricket, Mihir Bose penned: “There were stories of his running a nightclub in Paris.” But the identity of that “wife” and the reason behind running that niterie in Paris remained unknown, unverified and undocumented until Syer introduced me to Dr Ranjit Singh Malhi, author of the book Sikhs in Malaysia: A Comprehensive History, published last year. Malhi, whose chef-d’oeuvre has a comprehensive chapter on Singh, informed, “Singh had an affair with an African American jazz singer named Myrtle Watkins, later known by her stage name Paquita. Watkins, who came to India during the winter of 1935, used to perform at the Harbour Bar in Taj Mahal Hotel and instantly bowled over the ‘picturesque’ cricketer.”

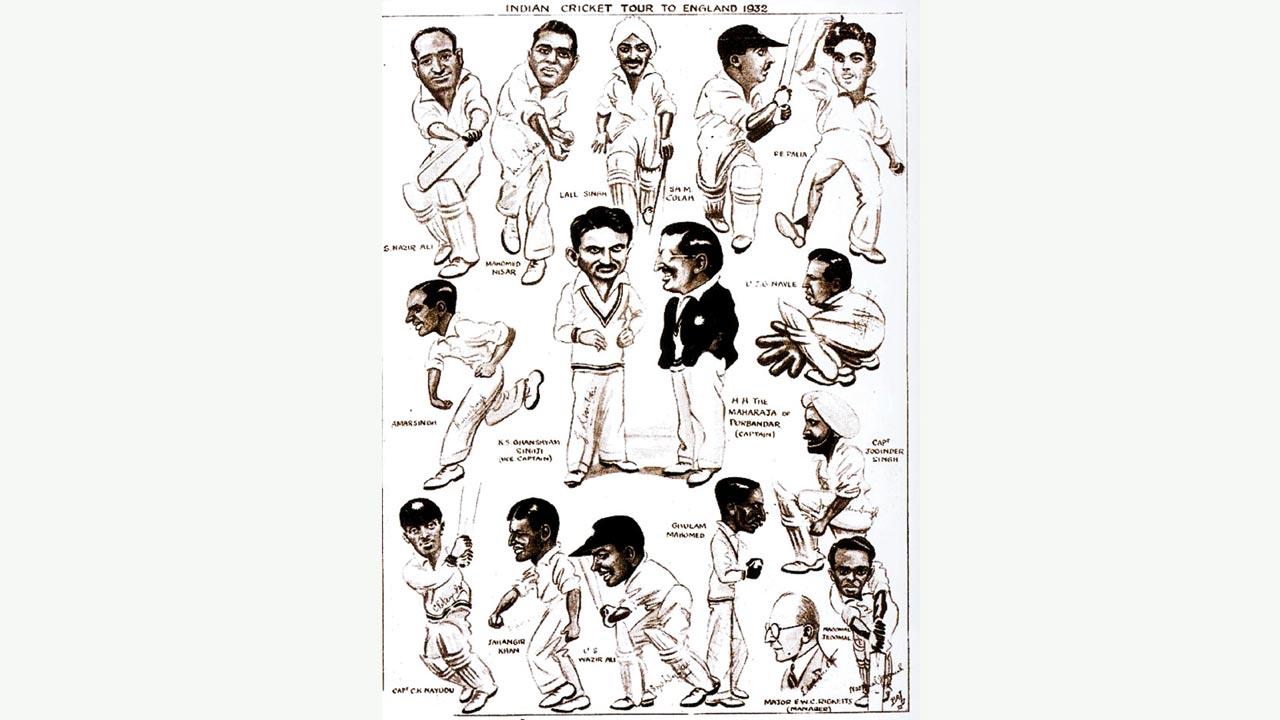

A sheet of caricatures of the 1932 Indian team in England. Pic courtesy/Personal collection of Tariq Shamsi

A sheet of caricatures of the 1932 Indian team in England. Pic courtesy/Personal collection of Tariq Shamsi

“Singh left for Paris in March 1936 to be with his prima donna paramour in the City of Love and subsequently ran a nightclub in the French capital before parting ways with his American partner and returned to Malaya [now Malaysia] in 1939,” the Malaysian author mentioned. “My granduncle was never married to Watkins, but they were in a live-in relationship for a few years,” clarified Captain Tariq Shamsi, whose mother was Singh’s elder brother Santha Singh Gill’s elder daughter Ajmer Kaur (who changed her name to Neelum Shamsi following her marriage as per Islamic ritual), and father was Brigadier Baseer Shamsi.

Interestingly, Dubai-based retired Pakistan Army officer Captain Tariq Shamsi was one of the last missing pieces of my jigsaw puzzle to complete the biographical sketch on the inconspicuous but incredible life of Singh. Shamsi’s Wikipedia entries without citation did convince me that he was the same Tariq B Shamsi, whose father Brigadier Shamsi got married to Singh’s niece when he was posted in Kuala Lumpur from Burma (now Myanmar) as a Captain in the eighth Punjab Regiment of the British Indian Army. However, it was almost like looking for a needle in a haystack for an Indian civilian like me to find a retired Pakistan Army officer with the frosty relationship between the two neighbouring countries reaching an unusually frigid state. But after four years of intense search and earnest outreach activities, rounds after rounds of Google searches and, eventually, an un-replied message to a random American phone number that turned out to be of a Pakistan Army veteran resulted in an early morning message from none other than, his “course mate,” Captain Shamsi. Once Dubai-based Shamsi obliged to my interview request, what followed next was an edge-of-the-seat story of the magnificent-turned-tragic life of the ever-jovial Indian Test cricketer.

Lall Singh with Tariq Shamsi’s mother and his niece. Pic courtesy/Personal collection of Tariq Shamsi

Lall Singh with Tariq Shamsi’s mother and his niece. Pic courtesy/Personal collection of Tariq Shamsi

“He was born with a silver spoon as the Gills were one of Malaysia’s most prominent and affluent third-generation Indian-origin families. They had close family ties with the Patiala royals, which eventually helped him pursue his career in India under the aegis of the all-powerful Maharaja Bhupinder Singh of Patiala,” Shamsi articulated. While talking about Singh’s baptism with cricket, Malhi summarized, “Lall’s cricket journey began at the age of 14 when he played for the prestigious Victoria Institution. When he was hardly 16, he made the Selangor team and the Federated Malay States XI. By 1931, Lall was already a well-known cricketer in Malaya and caught the eye of Maharaja of Patiala and the other Indian cricket patrons ahead of the trials for the England tour in early 1932.” The rest, as they say, is history.

However, the fag end of Singh’s short-lived Test and first-class career coincided with the beginning of his intercontinental and interracial romance with Watkins. The Alabama-born and Baltimore-based singer-dancer, who was born as Myrtle Dillard before her marriage to a certain Cephus Watkins, arrived in Mumbai from Venice for six months with Leon Abbey’s orchestra in September 1935 but faced some work permit issues before she, also joined by Opal Cooper, started performing at the Harbour Bar at Taj Mahal Hotel and its next-door neighbour Green’s (where the current Taj Mahal Tower was built) Ballroom. A sprightly Singh was staying in Mumbai those days to play for the Hindus at the Bombay Quadrangular tournament and the matches against Jack Ryder’s touring Australian side. “My happy-go-lucky grand uncle loved his drinks and was a frequent visitor to the famous watering hole at Taj Hotel, where he was smitten by the jazz artist, who had just overcome a bout of malaria,” Shamsi said. After scoring a magnificent century in the Bombay Quadrangular, Singh played the first unofficial Test against Jack Ryder’s Australian team in Mumbai in December 1935. But that turned out to be his last appearance for the Indian team as “there was a murder attempt on Singh in early 1936.”

“His proximity to the mighty Maharaja of Patiala made some people within his coterie jealous about my grand uncle, who was serving the majesty as his aide-de-camp,” Shamsi claimed.

That was the tipping point in Singh’s life. He was grievously injured but survived. Meanwhile, in America, Watkins’s estranged husband died of stomach cancer. “Singh left no stone unturned to woo her, and he somehow convinced the damsel in distress to make a new beginning in Paris,” his grandnephew, who had many memorable meetings with Singh and spent quality time with him in London and Paris, revealed, adding, “He once took me to the nightclub that he set up for Watkins and I still remember it was on the Boulevard Saint-Michel after he transferred the property to a new owner.” But after their break-up and the World War breaking out in Europe, Singh returned to his hometown of Kuala Lumpur, where his life took a terribly tragic turn.

“In June 1942, my maternal grandfather SS Gill was arrested for helping British Army officers escape from Malaya to Singapore. His brothers Bishen Singh Gill and LS, as Singh was known in the family, were also arrested. All their assets, including three houses, a rubber plantation and a gold mine, were confiscated by the Japanese. Within three months, SS Gill and BS Gill were hanged by the Japanese occupation forces, and Singh, who was spared from death due to his stature, was sent to a slave labour camp in Borneo,” Shamsi narrated, adding, “Singh managed to escape from the captivity of the ferocious Japanese invaders and returned to Kuala Lumpur in August 1945. Believe it or not, he was one of the six survivors among the 2500-odd prisoners, thanks to his daredevil fleeing act from the jaws of death. When he was reunited with his mother and two nieces [my mother Ajmer Kaur and her younger sister Amer Kaur], he was a mere skeleton of the person he used to be. He had been tortured so badly that his own mother initially refused to recognise him as her frail son without a turban.” The Pakistan Army veteran’s emotional words on the phone about his larger-than-life Malaysian granduncle. “Incidentally, my flamboyant granduncle, who caught many eyes for his snow-white turban in England in 1932, was forced to shave his head and beard while in Japanese captivity and after that, he never again grew his hair or beard or wore a turban until his death.”

Shamsi continued, “Once Japan surrendered to the Allied forces on September 5, 1945, Singh was left with looking after his ailing mother and two nieces as the family had been left penniless due to the Japanese occupation of Malaya. The uncompromising Sikh with his amour propre had never worked in his life before and was too proud to knock on anyone’s door for help. But after his mother’s death in 1946, abject property forced him to start looking for a job, and the only one he could find in that post-war-ravaged Malaya was that of groundsman at the prestigious Selangor Club in Kuala Lumpur.”

However, a few years later, in 1950, the former Indian Test cricketer was said to have been spotted by Sultan Sir Hishamuddin Alam Shah Al-Haj, the Sultan of Selangor at the club and the royal, who was a friend of the Gill family, was shocked to see Singh working as a groundsman. Hearing his penury and plight, the Sultan subsequently rehabilitated the estates of the Gill family to Singh following a cumbersome process ranging three years and involving the transfer of most of the estates, fixed and moveable assets belonging to his departed mother. “Since then, Singh had lived with much dignity until dying peacefully on November 19, 1985,” Malhi commented. Interestingly, he was one of the oldest players to attend the Golden Jubilee Test in Mumbai (then Bombay) in 1980 after being invited by the BCCI.

Shamsi stated, “Although he hardly spoke about his cricketing career, the humble man used to passionately follow Indian cricket and was in touch with the likes of Lala Amarnath and Vinoo Mankad for a long time. The blithesome bohemian spent the rest of his life travelling abroad, mostly to his favourite holiday retreat of Paris in summer.

“However, the heartbroken man never got married and died a bachelor. In the last days of his life, he was looked after well by a Chinese couple in Kuala Lumpur.”

Nonetheless, Singh lived his later life king-size. The high-spirited Sardar, whose cricketing career in India was primarily attributed to the King of Patiala, Shamsi quipped, “was particularly fond of his Patiala Pegs and unfailingly raised a toast during his regular visits to Selangor Club.”

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!