Writer Anuradha Kumar turns armchair detective for her new book, where she investigates the story of two Indian men with the same name, who lived in 20th century America and whose paths crossed on more occasion than one

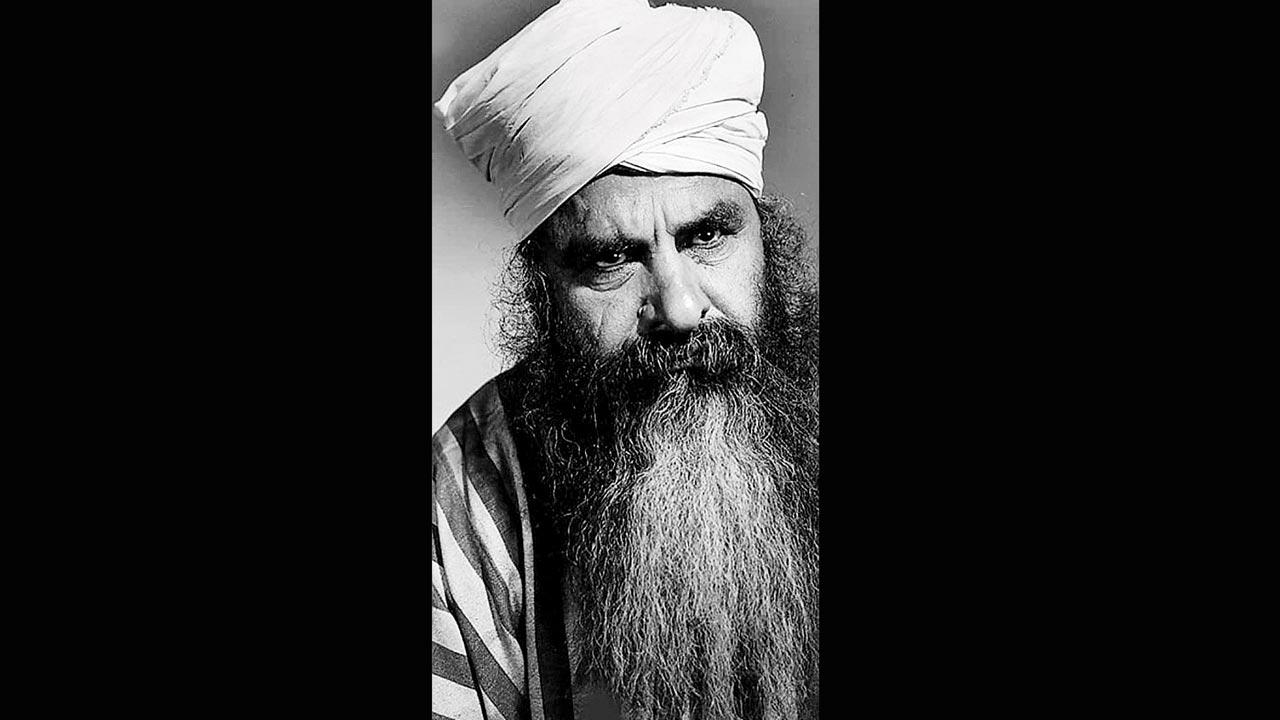

Bhagwan Singh was one of the most prominent forces of the Ghadar Party in California, before he took on a new avatar, remodelling himself as Bhagwan Singh Gyanee, a spiritual guru. Pic courtesy/en.wikipedia.org

Bhagwan Singh and Bhogwan Singh. These two men with names, distinguished only by the letter “O”, stirred the curiosity of New Jersey-based author Anuradha Kumar around six years ago. Her interest in their lives began when journalist Nandini Ramnath encouraged her to work on the early South Asians in Hollywood for a news site. While researching on the usual suspects—actors Sabu Dastagir and Lal Chand Mehra to name a few—she came across the “turban wrappers” of Hollywood. “To my mind, this was a fascinating occupation,” she shares over a video call. Two things were happening simultaneously in early 20th century America: the country was entering a powerful imperialist phase, while also gaining a stronghold in the movie business drawing British filmmakers by a dozen. It’s possibly why the orient began to captivate the imagination of American cinema. “They often needed turban wrappers to do the job [to wrap and unwrap the piece of clothing from their actor’s head]. The turban wrappers, on their part, sold their occupation very smartly. They claimed that every caste and ethnic group in Asia, more specifically India, wore their turbans differently, and mixing one for the other, could cause riots in the orient,” says Kumar. At least that was the argument that Bhogwan Singh made, when he was given the job. He went to become Hollywood’s foremost turban wrapper.

ADVERTISEMENT

Around the same time, Kumar had been reading about the Ghadar Party revolutionaries, who had spread along the west coast in the US. At the forefront was one Bhagwan Singh, who had been deported from Vancouver in 1913. He became one of the most prominent forces of the Ghadar Party in California. “I imagined what it would be like for a rebel, who is being chased by authorities, to live in America.” Bhagwan had the ability to disguise himself and assume different identities. During the World War I years, he had travelled under different names across the US and East Asia—he had adopted over 17 different aliases. When he was apprehended at Jolo, off the islands of the Philippines in 1915, the police found a load of false moustaches and wigs on him. “If he could disguise himself to evade authorities, why couldn’t he be a turban wrapper in Hollywood?” Kumar remembers asking herself. This hypothesis of whether the misspelling was simply an alternative name for the same person seemed to occupy her thoughts enough to chase the life story of these two men, and in the process that of others.

Bhogwan Singh became Hollywood’s foremost turban wrapper. He also did small roles in several films that had Oriental themes. Pic courtesy/imdb.com

Bhogwan Singh became Hollywood’s foremost turban wrapper. He also did small roles in several films that had Oriental themes. Pic courtesy/imdb.com

Her soon-to-release book, One Man, Many Lives: Bhagwan Singh and the Early South Asians in America (Simon & Schuster and Yoda Press), sees Kumar play armchair detective as she digs through directories, archives, newspapers, pamphlets and films to uncover the trajectories of the two men. “Some of the records are surprisingly detailed,” she says. “From whatever I found, it seemed like these two men lived too close to each other, sometimes in the same city. When one of them was in the limelight, the other somehow dropped out [of the scene],” she mentions.

The South Asian population in America was a tiny and insignificant one in the 1920s. Following the landmark Bhagat Singh Thind judgement of 1923, which denied naturalisation to Thind—a native Hindu who argued he was ‘Caucasian’ and ‘Aryan’—the immigration laws only became more rigid. There were just about 3,000 or more South Asians, says Kumar, adding that this made it easier for her to trace these two men.

Anuradha Kumar

Anuradha Kumar

Kumar, who is the author of Coming Back to the City: Mumbai Stories and The Hottest Summer in Years, has moved to non-fiction with this new book. But as a student of history, who had dreamed of pursuing a PhD but was unable to do so, this book became a sort of redemption, she admits. Her research for this one, went far and wide, beyond the protagonists she was chasing. Context is important, she says, explaining why it was important to tell the stories of other South Asians who lived during that time, too. “Every person lives their life in a certain context. The choices that both Bhogwan and Bhagwan made were decided by the circumstances they found themselves in. In a way, their lives seem to reflect the restraints that other South Asians also faced in America at the time. This book also tells that other vital story of the fight for citizenship by immigrants.”

The arguments in the book are an unusual attempt to explore where and how the lives of Bhogwan and Bhagwan intertwined. For every “what if,” there is a historical fact, thorough enough for you to wonder if there were indeed two people, or one. In the 1920s, Bhagwan took on a new avatar, remodelling himself as Bhagwan Singh Gyanee, a spiritual guru. This came following a complicated relationship with the Ghadar Party, and an imminent threat of deportation after some members were hanged. In the book, Kumar writes about an advertisement that appeared in some west coast papers. “Bhagwan Singh Gyanee, whose face appeared in profile, was described as a mastermind and philosopher who had travelled the world and was now finally in the US. He had grown up in the Punjab, had mastered the scriptures at an early age, and was hence called ‘gyanee [wise],’” Kumar writes. “Bhagwan had cheated some of his colleagues in Ghadar. He wanted to cover up that past. And he managed to do that very well for many years. But it was a precarious existence, which is why he also doubled up as an actor sometimes,” she says. There was this one occasion when both Bhogwan and Bhagwan worked in the same film, the Korda Brothers’ Jungle Book (1942). “But, only one of them [Bhogwan] was credited,” she says. We will leave it at that.

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!