Ecologists and green warriors want to know how a city that’s swiftly losing green cover to urban development has managed a spot on UN agency’s Tree Cities of the World list

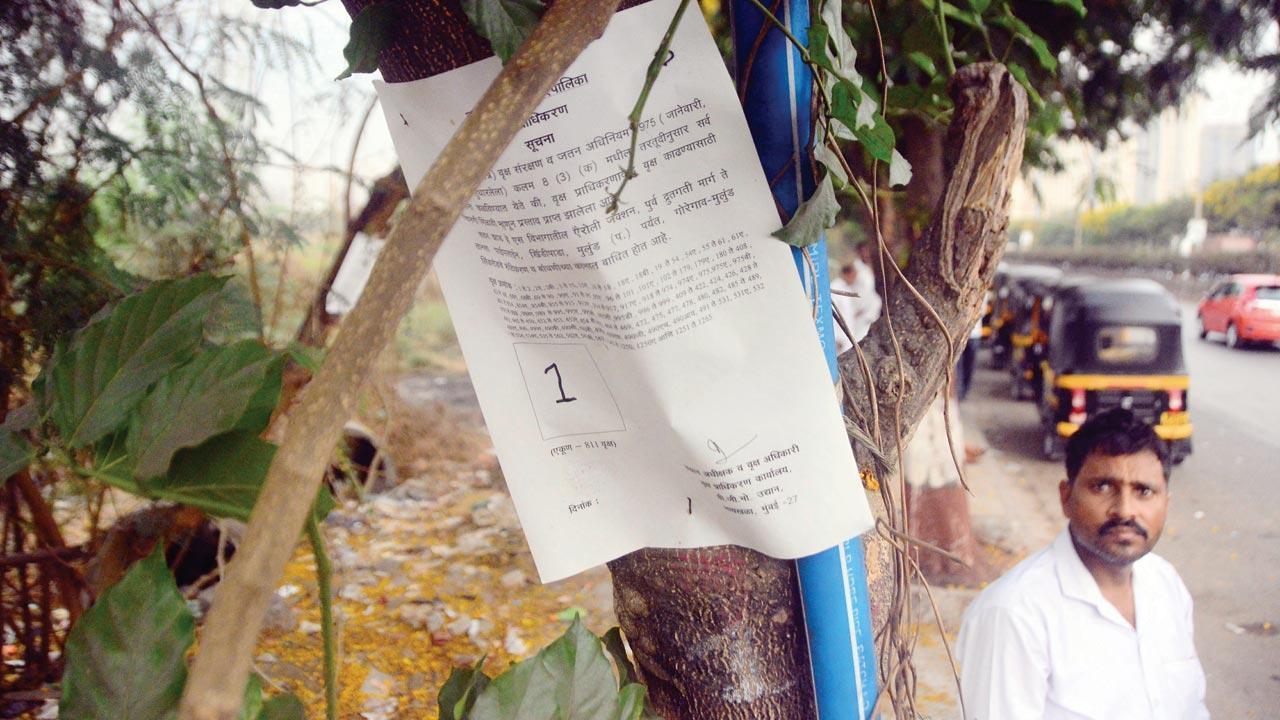

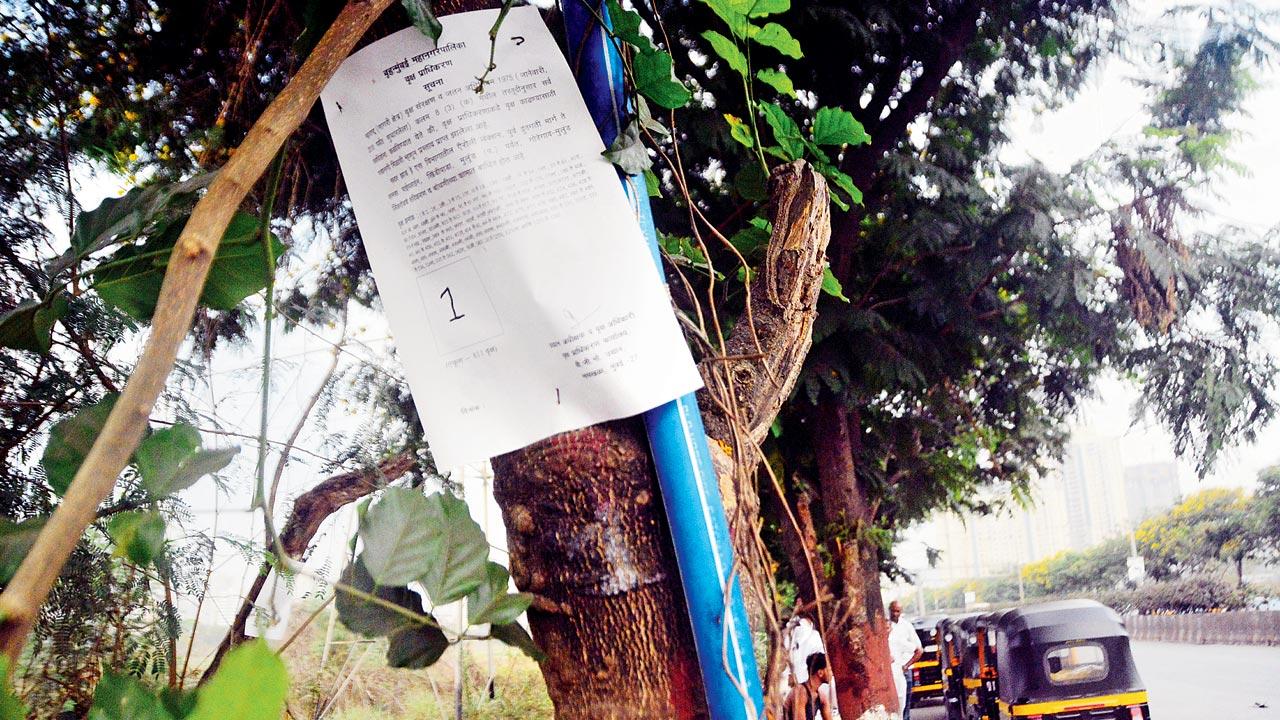

A notice hangs on one of the 1,000 trees on the Goregaon-Mulund Link Road, which have been marked for cutting for a proposed road-widening project. Pic/Sameer Markande

For any city, environmental awards are a reflection of its green health. But, when Mumbai received one such honour recently, it was received with a pinch of salt. The Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO), a specialised agency of the United Nations, last week recognised Mumbai as one of the 2021 Tree Cities of the World for planting 4,25,000 trees over 25,000 volunteer hours. The metropolis was among 138 cities from across 21 countries to find a mention in the list, sharing space with Hyderabad, the only other Indian city to join this distinguished company. Mumbai’s environmental activists and ecologists though, are hardly impressed. With a major part of the city currently on stilts, either for the ongoing Metro or Coastal Road projects, and swathes of green land taken over for redevelopment, they wonder how Mumbai made the cut.

ADVERTISEMENT

To receive such a recognition, a city must meet five core standards, including delegating responsibility for the care of trees to a Tree Board; a law or an official policy to govern the management of forests and trees; an updated inventory or assessment of the local tree resource so that an effective long-term plan for planting, care and removal of city trees can be established; a dedicated annual budget for the routine implementation of the tree management plan, and an annual celebration of trees to raise awareness among residents and to acknowledge those who carry out the tree programme. On paper at least, Mumbai fits this criteria. The laws are in place, and so is the sentiment, say experts. But, they aren’t sure if it’s robust enough to guarantee protection of our green cover.

Preeti Ghanekar, who was part of the citizen’s group that spearheaded the Mulund Micro Forest project, which involved creating a Miyawaki forest inside a 100 sqm plot in BMC’s Raosaheb Ramrao Patil Garden at Hari Om Nagar, Mulund East, shows the withered trees on the stretch. The BMC had taken over its upkeep last year. Pic/Satej Shinde

Preeti Ghanekar, who was part of the citizen’s group that spearheaded the Mulund Micro Forest project, which involved creating a Miyawaki forest inside a 100 sqm plot in BMC’s Raosaheb Ramrao Patil Garden at Hari Om Nagar, Mulund East, shows the withered trees on the stretch. The BMC had taken over its upkeep last year. Pic/Satej Shinde

According to the last BMC Tree Census of 2018, as reported by Indiaspend.com, “nearly 94 per cent of Mumbai has been concretised over 40 years”. While the ideal tree-human ratio is 8:1, Mumbai has only one tree for every four persons, the census revealed. A 2015 study, pointed out that Brazil had 301 billion trees (1,494 per person), while the US had 716 trees per person. A lot of work still needs to be done for Mumbai to be really deserving of such a title, feel environmentalists.

Ecologist Anand Pendharkar, who is also the CEO of the SPROUTS Environment Trust, is more critical. “Where are the trees?” he asks. “All of SV Road, from Andheri to Khar and Bandra, was once lined with trees. They are all gone. Shivaji Park is naked and barren. DN Nagar Road [in Andheri West] lost about 400 trees. We have lost thousands of trees to the Metro lines. Byculla zoo and IIT Powai have also opened out,” says Pendharkar, while sharing cold facts. “Has this tree loss been compensated for adequately? I am a scientist. I will only believe, if you show me the numbers.”

In April 2017, over 25 trees that were uprooted due to the Metro 2A construction and transplanted to a plot in Aarey, had died suddenly. Locals had alleged that the trees weren’t being watered on a regular basis. File pic

Rampant tree cutting for development projects has irked both green warriors and citizens. Last year, an RTI query by BJP MLA Ameet Satam revealed that between February 2010 and July 2021, the BMC’s garden department gave private players permission to cut 21,253 trees and to transplant 17,964 trees. The BMC, on the other hand, was given permission to cut 8,843 trees and transplant 10,075 trees. Environmental activist Zoru Bhathena, who campaigned against the former BJP government’s decision to cut trees at Aarey Colony to make way for the Metro car shed, says that the numbers only reflect official data. “Unofficial tree cutting is almost equal or perhaps, event double the official count,” he tells mid-day, adding, “At least until two years ago, 13,000 trees were being axed for development and miscellaneous projects annually.” Apart from redevelopment projects, the city also loses trees to natural calamities, like heavy rain and cyclone, or due to manmade disasters, like concretisation of foothpaths, which kill them slowly.

On the Goregaon-Mulund Link Road, over 1,000-odd trees have been marked for cutting, for a proposed road-widening project. “Incidentally, these trees were planted following a road-widening project that was done less than a decade ago. It’s a complete mockery of the system. Our trees don’t have a permanent space. It’s liable to be cut and shifted at the whims and fancies of the authorities,” says conservationist Stalin Dayanand, who works with the environmental NGO Vanashakti. “Can we not design our [infra] projects around our trees?” asks Pendharkar. “We’ve lost rare, heritage trees. Look at what has happened to our baobabs,” he says about the African-origin deciduous plant with a swollen barrel-shaped base that’s also called the Tree of Life. In 2020, an inquiry was instituted after Navi Mumbai’s only baobab near the Jain temple was hacked by the Navi Mumbai Municipal Corporation (NMMC) despite an assurance in 2015 to protect it from encroachers. It was said to have a regal 2.5-metre diameter.

Around 1,000-odd trees along the Goregaon-Mulund Link Road are set to be axed for a proposed road-widening project. Environmentalists feel that infra projects should be designed around trees. Pic/Sameer Markande

Around 1,000-odd trees along the Goregaon-Mulund Link Road are set to be axed for a proposed road-widening project. Environmentalists feel that infra projects should be designed around trees. Pic/Sameer Markande

Last year, after mid-day reported about the plans to axe a centuries-old African baobab at Santa Cruz West to make way for the Metro line, State Minister of Environment and Climate Change Aaditya Thackeray assured that the tree would be saved, and efforts made to protect other trees coming in the way of Metro projects here.

As per the earlier Maharashtra (Urban Areas) Protection and Preservation of Trees Act, 1975, two new saplings had to be planted within 30 days of a tree being felled, or within the time stipulated by the tree officer. This law was amended in 2021. While in place, it barely had any impact on conservation, because it wasn’t followed to the tee, says Bhathena.

A plantation site in SGNP has young trees scattered throughout the patch. Pic/Anurag Ahire

A plantation site in SGNP has young trees scattered throughout the patch. Pic/Anurag Ahire

As Stalin tells this writer: “The MMRCL [Maharashtra Metro Rail Corporation Limited] claims to have planted 25,000 saplings in Sanjay Gandhi National Park. Find 200 and I will give you a treat.” In 2019, after MMRCL and the state government had claimed that 25,000 “fully grown trees”—12 ft height and six inch girth—had been planted as compensatory afforestation for cutting down trees inside Aarey Colony, the conservationist had personally visited the site, where he found not more than 5,000 saplings. “They claimed six-inch girth; I can wrap my little finger around them,” Stalin said in a video that he later shared on social media. The site chosen for the plantation drive was also filled with debris and stones, which explained why some of the trees had been uprooted.

Pendharkar states that planting thousands of saplings, isn’t enough. “Only if they survive up to 20-25 years, can they be called trees.” Eighty per cent of the time, these saplings die. Recently, Pendharkar carried out a plantation drive along the Oshiwara river. “There have been mixed results over there as well, because people visit the place, eat, dump garbage, drop lighted cigarettes or bidis, or burn the garbage. This destroys the saplings and surrounding vegetation. It defeats the purpose of the ecological restoration [rewilding] we are trying to do. The local administration doesn’t even ensure its protection.”

Stalin Dayanand, Sanjiv Valsan, Dr Sashirekha S Iyer and Zoru Bhathena

Stalin Dayanand, Sanjiv Valsan, Dr Sashirekha S Iyer and Zoru Bhathena

In SGNP, there is a site dedicated to plantation, which for the longest time didn’t yield great results, says Bhathena. When the mid-day photographer visited the site, young trees of average height were scattered throughout the patch. “When choosing a plantation site, authorities should first investigative whether the patch is conducive for plantation. Even in a forested stretch, if land doesn’t have trees, they need to figure out why it is the case?”

Speaking with mid-day, Manisha Patankar-Mhaiskar, principal secretary, Department of Environment and Climate Change, admits that the previous act wasn’t effective enough. “Earlier, even if you axed a 50-year-old tree, you had to plant only two saplings in lieu. We realised that the compensatory tree plantation was highly inadequate, and that transplantation, as per surveys, was yielding poor results. Now, as per the new amended act [2021], you need to plant as many healthy saplings, as the cumulative age of the trees cut and transplanted. So, if you cut two trees that are 20 years old each, you need to plant at least 40 trees. We have also asked the local authorities to earmark certain areas for these kinds of plantations,” she says, adding that they have also specified that saplings need to be at least 18 months old, so that they have a better rate of survival.

Anand Pendharkar, ecologist and Manisha Patankar-Mhaiskar, principal secretary, Department of Environment and Climate Change

Anand Pendharkar, ecologist and Manisha Patankar-Mhaiskar, principal secretary, Department of Environment and Climate Change

“We are even encouraging planting of indigenous and native species as far as possible.”

The Maharashtra government has also amended the Tree Act to introduce provisions for the protection of ‘heritage trees’ (50 years and older), and the establishment of a state tree authority to oversee all activities related to protection of trees. State agencies have been asked to work out a plan to accommodate heritage trees as far as possible. However, a source said that while the urban act has been amended for heritage trees, the rural act is yet to be amended. This means that all heritage trees along the highways, and outside city limits, won’t enjoy such protection, making it easier for agencies to skirt the law.

For transplantations to be successful, it needs to be done by an expert, says Bhathena. “It may seem like a bizarre example, but you can’t call your dentist and tell him to transplant a kidney.”

Botanist Dr Sashirekha S Iyer, who was part of the expert committee of the BMC’s Tree Authority in 2019, says that if transplantation is done sincerely, it will serve the purpose. “If transplantation isn’t done systematically, the tree goes into a state of shock. The root system also needs to be protected. It has to be covered with sufficient parent soil. When that’s not done, the roots begin to dry. Such a tree doesn’t stand a chance to survive.” As a Tree Authority member, she recalls questioning the agency meant to transplant trees in Aarey for the Metro 3 project. “They had shown us an area where they had transplanted some trees right opposite the site from where they were uprooted. They were all planted in a row. That’s not how it should be done. You are displacing a tree from one parent site to another. There are a lot of factors particularly soil fungi, that help a tree grow. We call it the wood wide web [an underground network of fungal mycelia and flora that connects trees in the forest].” Environmentalist Sanjiv Valsan says that rewarding contractors for tree survival might be a good step forward. “At present, we don’t have a system in place to incentivise successful transplantations. If we were to make their fees payable in spaced out installments that depend heavily on tree survival, along with a basic transplantation SOP [standard operating procedure], they would be likelier to do their jobs thoroughly.”

Another grand, but controversial project that the BMC has begun to implement in its open spaces is the “Miyawaki urban forest”, a technique pioneered by Japanese botanist Akira Miyawaki. The Miyawaki method is known to be effective in creating forest cover quickly on degraded land. The idea is to grow trees native to the area on a smaller patch, to create thriving and resilient ecosystems. The trees planted by this method grow much faster, capturing more carbon. But, Pendharkar challenges the claim. “The idea of calling it a micro forest, is foolhardy. Is a river originating there, are monkeys living there, do crocodiles inhabit the place?”

As part of its first phase, the BMC planned to grow 2.21 lakh trees in 43 places. While this might seem like a “panacea for urban woes”, Jayraj Nayak, a tree enthusiast, says in Mumbai, 90 per cent of those implementing Miyawaki, lack knowhow. “They rely on YouTube tutorials, and that’s not how it is done. You need to pick the right native species to really have a good Miyawaki.”

Back in July 2019, much before the BMC mooted the idea, residents of Mulund East’s Hari Om Nagar, came together to create a Miyawaki in an 100 sqm plot that was given to them by the BMC. Uttara Ganesh, who was part of the group that spearheaded the initiative with the help of Sushant Bali, an environmentalist, says that after raising funds for the project and successfully overseeing it for two years, they handed it over to the BMC last year. “They wanted to lease the Mulund Miyawaki Forest to a bidder; since we aren’t an NGO, we couldn’t bid for its upkeep. Now, it’s in a ruinous state. The plot isn’t watered regularly, due to which the plants have started drying up. We didn’t do all this for name or fame, we just wanted a nice green cover in our area,” she says.

Dr Iyer, a retired associate professor of Mithibai College, who had resigned from the Tree Committee, after she alleged that she was falsely accused of giving a go-ahead to uprooting 2,646 trees in Aarey, says, “You can’t have an expert and not respect their decisions.” “Every time I wanted to speak, I wasn’t given a chance. I didn’t feel heard. What’s the use of having us on the committee then?”

4,25,000

No. of trees Mumbai planted over 25,000 man hours for which it was recognised last week

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!