Danish Husain’s new play on legendary lyricist Sahir Ludhianvi draws inspiration from his life and work, exposing a sea change in cinema’s evolving lyrics

(From left) Singer Srijonee Bhattacharjee, actor-director Danish Husain and Vrinda Vaid perform a Ludhianvi song inside the green room at Prithvi Theatre. Pic/Aishwarya Deodhar

Main marna nahin chaahta,” were the last words of a towering resident of Juhu.

ADVERTISEMENT

Fifty years later, he has 63,000 hashtags to his name on Instagram, the digital residence of millennial and GenZ South Asians, who didn’t even witness the living legend.

In the same neighbourhood, Prithvi Theatre will today be staging Main Pal Do Pal Ka Shayar Hoon, a new play on the life and work of Urdu poet and Hindi film lyricist Sahir Ludhianvi or Abdul Hai, as part of the 11th Hoshruba Repertory Festival.

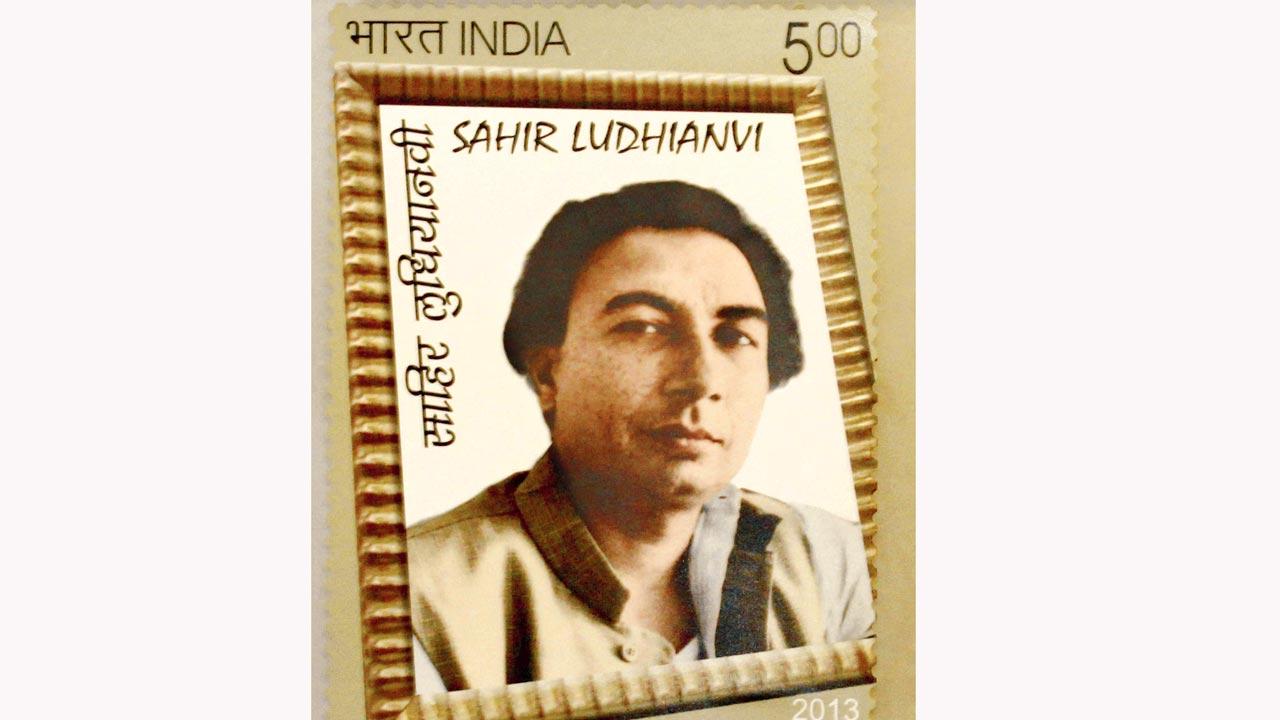

A postal stamp of Sahir Ludhianvi’s was released at the Rashtrapati Bhavan in New Delhi in 2013. Pic/Getty Images

A postal stamp of Sahir Ludhianvi’s was released at the Rashtrapati Bhavan in New Delhi in 2013. Pic/Getty Images

This play on Ludhianvi’s life by six performers, including four musicians simulating a 1960s recording studio, recreates popular film songs written by him. Actor Danish Husain has directed it and co-produced it with Hyderabad-based Amita Talwar of NGO Art for Causes. Husain combined scripts of two earlier plays on Ludhianvi, a first person solo-act written by Mir Ali Husain and an Urdu dastaan-goi performance by Himanshu Bajpai. “There will also be audio-visual slides of important events from Sahir’s life,” shares Husain.

For his co-producer Talwar, it had been a long-held dream to make documentaries on six of her favourite lyricists, including Ludhianvi; she ended up making only one on Kaifi Azmi for Doordarshan. “I always wondered who are the people writing these beautiful lyrics,” says Talwar.

Ludhianvi’s debut book Talkhiyaan (1943) is likely the most-sold Urdu poetry book after grand-man Mirza Ghalib’s. He was a 23-year-old, just out of college when he wrote the book whose poems also turned into our most-hummable lyrics, and romantic anthems, especially in albums from Pyaasa to Kabhie Kabhie.

Amita Talwar, Akshay Manwani and Kausar Munir

Amita Talwar, Akshay Manwani and Kausar Munir

Main Pal Do Pal Ka paints a vivid picture of this enigmatic writer who grew up in the penury and hardship that he wrote about. The exposition happens in Ludhianvi’s own voice, played by Husain, and an ensemble of characters not clearly defined, but in whom one can find hints of Ludhianvi’s composer pair SD Burman (Shantanu Herlekar on the harmonium) and Lata Mangeshkar (Srijonee Bhattacharjee on vocals). The other two musicians (Siddarth Nityanand Padiyar and Donald Krist on percussion and guitar, respectively) along with Vrinda Vaid ‘Haayat’ have third-person narrator-like roles.

It strings his story and context starting with his birth in Ludhiana, growing up in the company of his single-parent mother, and sisters; turning young with India’s freedom movement; choosing Lahore (Pakistan) during 1947 Partition but moving to Bombay (India) two years later to evade the whip on Communist intellectuals like him.

In Bombay, the poet and the committed Communist converged his heart and his craft, and wrote of the mazduur, mazloom, and the mehboob—the worker, the oppressed, and the beloved—only as a Sahir, a magician can.

It was a serpentine ride to enter lyric-writing. He took two years to break into the cinema industry with a fated meeting with composer SD Burman, who was at the top of his league already.

Until then, Ludhianvi did what everyone coming into Bombay with some social connections did—camp at friends’ houses and find odd-jobs to pay the bills. He, along with his mother, stayed at progressive writer Krishan Chander’s, earning his space by writing Chander’s drafts in a neat hand.

The foundation of his person and politics was already set when he came to write for cinema.

When he couldn’t pay his magazine contributor Shama Lahori shivering in flimsy clothing in Lahore’s bitter cold, Ludhianvi resolved not to be poor and to earn his worker’s due. “He demanded his own price, and he’s the first lyricist whose name appears prominently on film posters,” says Mir Ali, who along with Raza Mir has also written Anthems of Resistance, a book on progressive Urdu poetry.

He set the fees higher, and even earned the disapproval and boycott of star composers when he demanded that his fee be at par with composers’ (and a rupee more!).

He also did less-cheeky advocacy for lyricists, before the then Information and Broadcasting minister BV Keskar. The ask was granted, with each song, its writer’s name was announced over state broadcaster All India Radio: that’s how generations of listeners know the weavers of words that move us.

“Sahir saahab’s political ideology was not just for literary effect, it was his lived reality,” says Kausar Munir, contemporary lyricist and the first woman to win a Filmfare Award for lyric-writing.

On a state-organised event to commemorate Mirza Ghalib’s death centenary in 1969, Ludhianvi marked his presence by reciting a poem against the step-child treatment of Urdu since The Partition. Such treatment was multi-faceted, but notably at AIR, which banned film music for half-a-decade for its usage of Urdu lyrics, notes Anthems of Resistance. Just a year earlier, in 1968, the Indira Gandhi regime pushed The Official Language Resolution to promote Hindi’s usage. That project continues till date, by grouping regional languages under Hindi to inflate Hindi’s importance and its number of speakers. Hindustani (the common register of Hindi and Urdu) also vanished from the census as a consequence.

In 1957, when Guru Dutt and Ludhianvi collaborated on Pyaasa’s sharp lyrics, India was newly independent from British Rule, and the progressive cine artistes were fearless in criticising the regime’s inadequacies.

“Nobody wrote overtly political songs other than Sahir Ludhianvi,” says Akshay Manwani, the writer of Ludhianvi’s biography in English.

At other times, Ludhianvi’s truth-to-power lyrics were even deleted by the Censor Board. Jitni bhi buildingen thiin sethon ney baant li hain, footpaath Bambai ke, hain aashiyaan humaara (The wealthy have usurped all the buildings and left us to shelter on Bombay’s footpaths).

“Sahir saahab’s uniqueness lies in that he gave his socialist, secular even revolutionary thoughts a hopeful and poetic idiom,” says Kausar Munir. As in this Dhool Ka Phool song for Yash Chopra’s directorial debut, “Nafarat jo sikhaaye woh dharam tera nahin hai, insaan ko jo raundey woh qadam tera nahin hai [Your religion shouldn’t teach you hatred, your actions shouldn’t harm another person].”

Ludhianvi wasn’t the only one producing such lyrics. There were other progressive Urdu-poet-lyricists like Shailendra, Pradeep, Kaifi Azmi, Jan Nisar Akhtar, Ali Sardar Jafri and Majrooh Sultanpuri. Yet, he stood out. “Shailendra’s work is at a parallel with Sahir’s if not better,” Manwani says. Filmmakers would refer to Ludhianvi’s poems and accommodate his poetry into the film, while Shailendra would write according to the situation in the film, Manwani says.

The canvas of Hindi cinema was painted in Urdu by Ludhianvi and his contemporaries. “The word ‘sanam’ for beloved in common parlance may be the gift of Hindi film lyrics,” says Mir Ali. His book lists other such words: ilteja (request), jaan-e-man (my life), saaqi (wine-bearer).

“Contemporary lyrics don’t speak,” says Talwar, “It is a khichdi of Hindi, Urdu, and the intensity is absent.”

Munir attributes such construction of lyrics as a reflection of our times. “Our preoccupation is with the business of lyric-writing, providing commercial success,” she says. None of our spoken languages is pure anymore: whether it’s English, Hindi, or Urdu.

“A lyricist is a function of his times,” Manwani says. He feels it’s a pressure on lyricists to maintain older linguistic traditions, while everyone from actors and filmmakers have been allowed to evolve in style since Ludhianvi’s era.

All of them hold hope, though “Sahir will always be relevant,” Talwar says, and hopes for the younger generations to discover Ludhianvi through his romantic numbers that always wove in endearing nature imagery. Mir Ali believes Hindi cinema will continue to popularise certain aspects of Urdu vocabulary as it has. Urdu may also change in structure as it already has too, “but I see no imminent demise of Urdu.”

At the end of one of the final rehearsals of Main Pal Do Pal Ka, in Prithvi Theatre’s green-room, the troupe breaks into the Ludhianvi song that is the play’s title.

Husain and Shantanu, the SD Burman-character musician debate if they could depart from the pronunciation of the Urdu word for poet, shaa’ir, as in the original song. It was decided to deviate to pronouncing it as shaayar. It’s the common pronunciation of this word now, even though it incorrectly pastes a consonant sound over a vowel Urdu alphabet. Everyone still understood and enjoyed the meaning. Ludhianvi never died. “Main har ik pal ka shaa’ir hoon,” he remains a poet for every occasion, just as he’d wished.

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!