While India loses Khetwadi address of his youth to redevelopment, London remembers Dadabhai Naoroji for his role in our freedom movement with a plaque at his South London residence

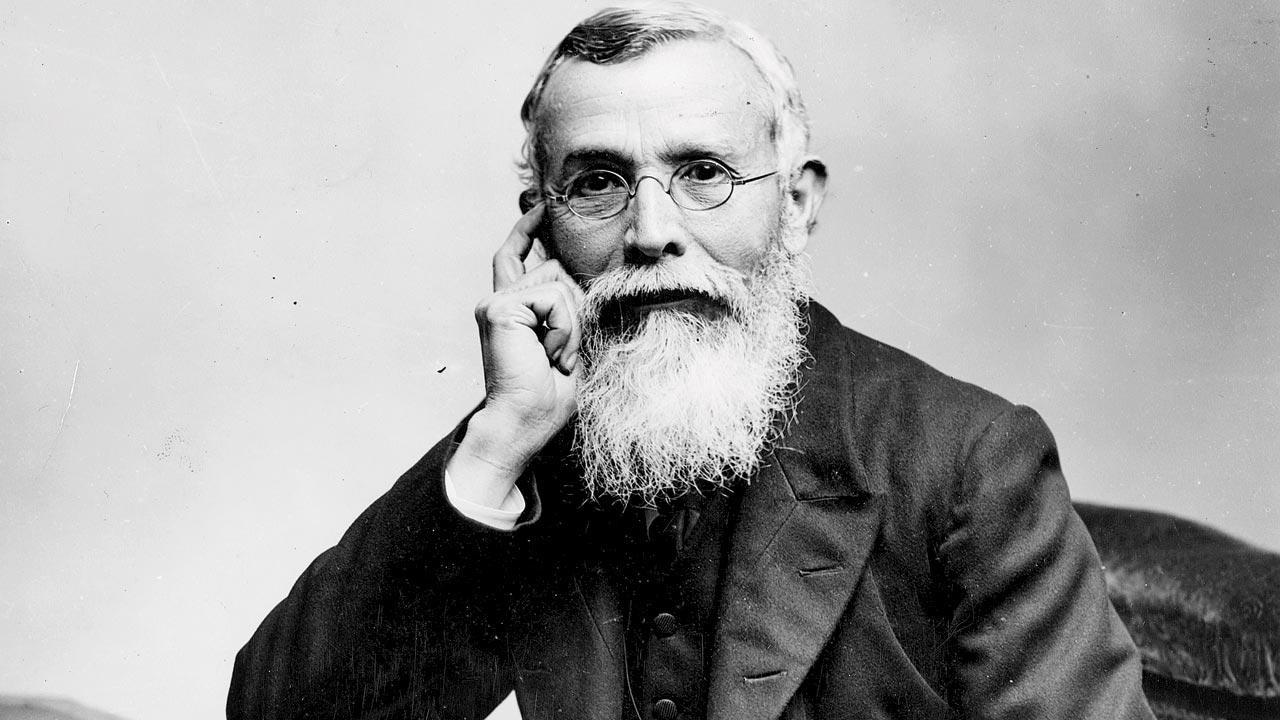

Between the 1850s and 1880s, Dadabhai Naoroji was involved in business, working in the cotton trade in Liverpool and then the City of London; he had an office at Great St Helen’s. But his primary purpose for being in Britain was political. Pic/Getty Images

From being described as a fire-worshipper to earning the nickname “Narrow-majority” for the tiny margin during his election win to the UK Parliament in 1892, Dr Dadabhai Naoroji’s life and times in England could not have been a walk in the park. In fact, when he decided to stand for elections, “the then Prime Minister [Lord Salisbury] asserted that the British public would not elect ‘a black man’ to Parliament’. It was a view he proved to be incorrect,” says Howard Spencer, historian at English Heritage in an email interview to mid-day.

ADVERTISEMENT

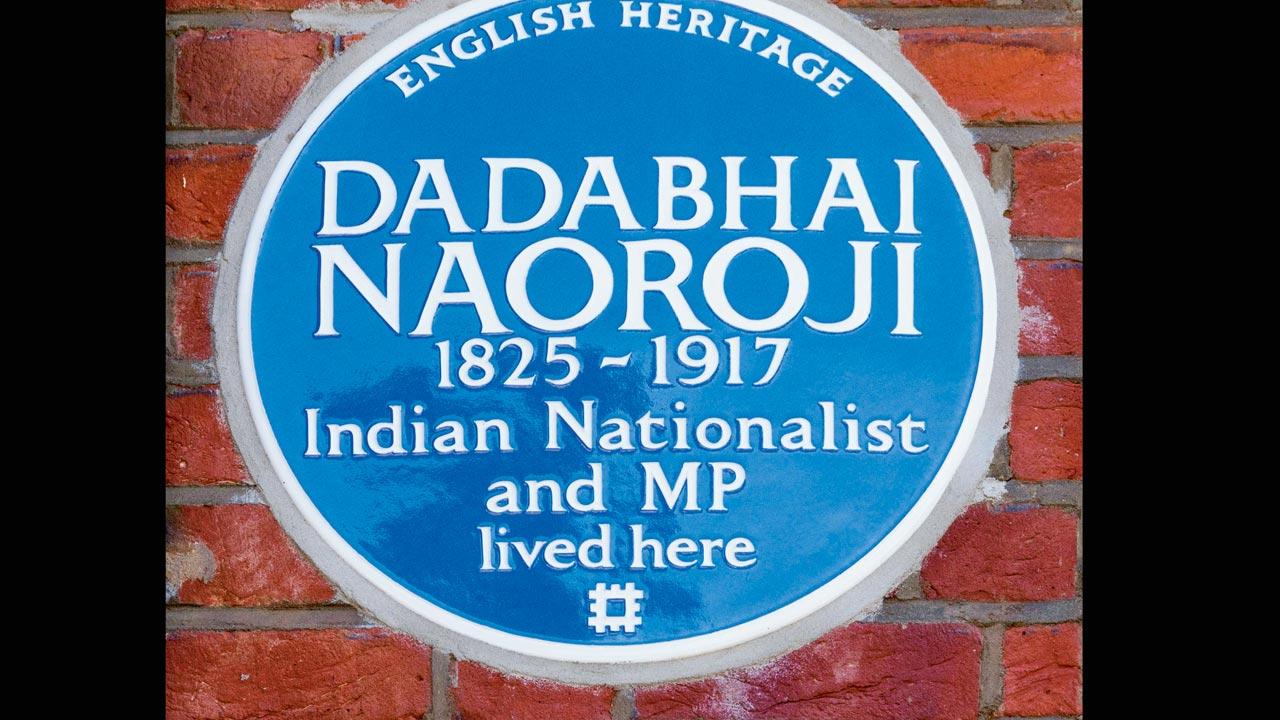

Last Friday, to acknowledge Naoroji’s contribution to India’s freedom movement across both countries, English Heritage unveiled a blue plaque in his honour at 42 Anerley Park, Naoroji’s residence in Penge, South London. “These plaques have been described as ‘portals to the past’ and offer an accessible reminder of the rich history associated with London’s built heritage. Though Naoroji lived at many residences during his time in London, this address was deemed to be the best place to do this [place the plaque] as it was his longest standing residence in the city,” says Spencer.

Naoroji moved frequently to different locations in London and his homes became meeting points for Behramji Malabari, Gopal Krishna Gokhale and Bhikhaiji Cama, among others. This address at 42 Anerley Park was his longest standing residence. Pics Courtesy/English Heritage

Naoroji moved frequently to different locations in London and his homes became meeting points for Behramji Malabari, Gopal Krishna Gokhale and Bhikhaiji Cama, among others. This address at 42 Anerley Park was his longest standing residence. Pics Courtesy/English Heritage

English Heritage is a charity that manages over 400 historic monuments, buildings and places. These include prehistoric sites, medieval castles, Roman forts and country houses. Naoroji’s plaque was originally suggested to them in 1992, but wasn’t shortlisted. The charity couldn’t reveal details of who originally proposed the plaque, owing to rules on data protection. The idea was revived by a staff member, now a senior historian on the plaque scheme, who decided to relook at the proposal. Spencer shares that after this particular address was finalised, they faced another hurdle. “Unfortunately, the then owner of the freehold could not be reached to gain approval for the plaque, causing further delay. Fortunately, the present freehold owners have been only too pleased to allow the plaque. We are grateful for their help in making this happen.” Finally, on August 10, members of London’s Zoroastrian community, who had helped organise a small event, came together to celebrate the honour bestowed on their beloved ‘Dadabhai’.

Naoroji spent nearly five decades in London. Between the 1850s and 1880s, he was involved in business, working in the cotton trade in Liverpool and then the city of London; he had an office at Great St Helen’s. “But his primary purpose for being in Britain was political. He believed that meaningful Indian political reform would be more achievable in London—specifically through the British Parliament, which had oversight of the Indian government, and which also included many MPs sympathetic towards Indian political and economic concerns—than in India,” says Dinyar Patel, author of Naoroji: Pioneer of Indian Nationalism, the definitive biography of the leader. The academic maintains that Naoroji and other early Congress leaders felt that the Indian government was too conservative and reactionary to consider any reform and hence, it was a better idea to go over their heads and achieve reform through Parliament. “The early Congress, therefore, was an international outfit; it coordinated political activity between two countries. Several of its leaders were critical of this strategy and by the early 20th century, some like Lokmanya Tilak, felt that Naoroji would be better off campaigning for change in India.”

Naoroji’s first attempt to enter Parliament was in 1886, when he stood as a Liberal candidate from Holborn, and was unsuccessful despite getting support from the likes of Florence Nightingale. It was Lord Salisbury’s reference [the time had not come for England to elect a black man] that put him in the spotlight. Later, in 1892, he won on a Liberal ticket from Finsbury Central in north London. Spencer reveals the reasons for his victory, “What we know is that 2,961 of the electors of Finsbury Central, were sufficiently impressed by Naoroji and his platform [which included home rule for Ireland and the right of women to sit in Parliament] to vote for him. This was enough to see him elected: he won by just five votes.”

By August 1897, Naoroji moved to this 72, Anerley Park address. Here, he helped to secure the appointment of the Welby Commission on the expense of the Indian Civil Service, and served as both, a member and an expert witness. He used it as a platform to air his views, which by this time were that the entire British Civil service apparatus should, eventually, be swept away,” informs Spencer. This did not happen in his lifetime, but the line he took inspired others, and the British Raj only outlasted him by 30 years.

The plaque’s unveiling last week was attended by members of London’s Zoroastrian community, including Malcolm Deboo, president of Zoroastrian Trusts Funds of Europe

The plaque’s unveiling last week was attended by members of London’s Zoroastrian community, including Malcolm Deboo, president of Zoroastrian Trusts Funds of Europe

Naoroji moved frequently to different locations in the city and his homes became meeting points for many expatriate Bombay residents or people associated with colonial Bombay: Behramji Malabari, Dinsha Wacha, Gopal Krishna Gokhale, Bhikhaiji Cama, the inventor Shankar Abaji Bhisey, and numerous students and professionals.

Author, broadcaster and English Heritage Blue Plaques panel member, Mihir Bose, who attended the unveiling ceremony, summarises Naoroji’s role thus: “He symbolises the complex relationship between Indian and Britain during the Raj,” reiterating the key part he played to investigate the wasteful expenditure of its colonists in India.

A Zoroastrian priest performs a jashan at the site

A Zoroastrian priest performs a jashan at the site

The blue plaque honour, say some, draws attention to how Naoroji is commemorated in Britain while he seems to have been largely been overlooked in India. Patel spells out the reasons, “We know that Naoroji was born and grew up in Khadak, located in today’s Bhendi Bazar, but we don’t know anything about the precise location of his home. The Naoroji family house in Khetwadi, between 4th and 5th Khetwadi lanes, was demolished during Naoroji’s lifetime to make way for Sandhurst Road. His last residence, The Sands in Versova [one of the original Saat Banglas], was demolished in the 1980s, and redeveloped.” He tells us of a very old house in Navsari which is erroneously referred to as Naoroji’s birthplace; although Naoroji stated that he was born in Bombay. “[Even so] That house probably has a family connection, and deserves to be preserved—it is a remarkable example of an old Parsi home; a fast-disappearing specimen which has all-too-often fallen prey to bulldozers for redevelopment,” believes Patel.

Dinyar Patel

Dinyar Patel

Citing this loss of Naoroji’s legacy, Patel signs off with a warning, “Until the process of historical preservation and commemoration is de-politicised [in India] and put into the hands of well-meaning professionals who are immune to political pressure, as it is in a place like London, I don’t see any prospect for change.”

End of a lineage

None of Naoroji’s descendants are alive. He had numerous grandchildren, but none of them, in turn, had any children. It is a telling representation of what has happened, demographically speaking, to the Parsi community, according to Dinyar Patel, who has created a tree of the family.

To explore the Naoroji family tree https://dinyarpatel.com/naoroji/family/

The Jinnah connect

While in London, barrister MA Jinnah was getting drawn towards politics. He assisted in Dadabhai Naoroji’s victorious 1892 election campaign. Jinnah even watched Naoroji’s maiden speech from the gallery in the House of Commons. His residence on 35 Russell Road, Holland Park, also got a blue plaque in 1955.

Go looking for these blue plaques in London on your next visit

Mahatma Gandhi

Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru

Sardar Vallabhbhai Jhaverbhai Patel

Swami Vivekananda

Veer Savarkar

Raja Rammohun Roy

Maharajah Duleep Singh

VK Krishna Menon

Ardaseer Cursetjee Wadia

Sir Syed Ahmed Khan

The Ayahs’ Home (It housed women who served British families and hailed mainly from South Asia. These domestic helpers served as children’s nannies, nursemaids and ladies’ maids)

Information courtesy: English Heritage

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!