A Bengali film actress and director’s centenary has initiated efforts towards the restoration of her films, bringing attention to how family archives can contribute to the building of larger public histories while shining a light on the work of women professionals

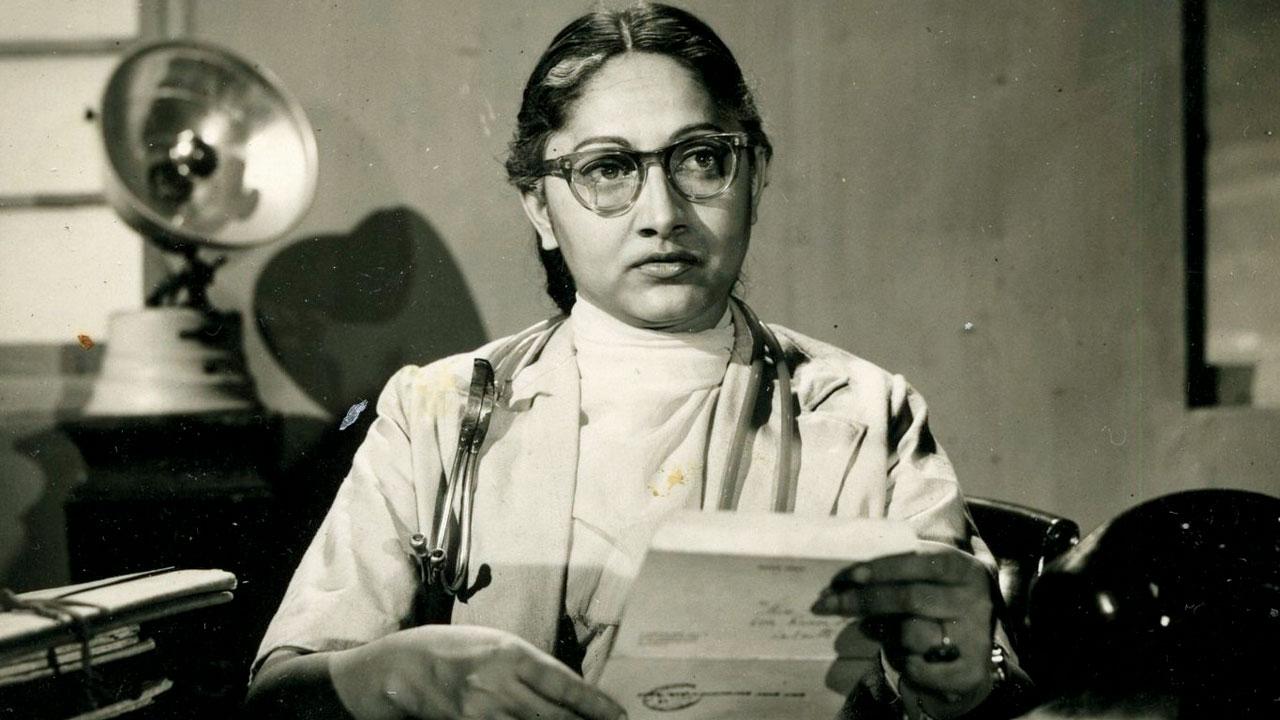

Arundhati Devi in Bicharak, 1959

On April 28, at Kolkata’s Nandan 3, the Arundhati Devi Centenary Project was launched with two film screenings of the Bengali film actress-director Arundhati Devi. The discussions began about eight months ago, son Anindya Sinha, professor at the National Institute of Advanced Studies, Bengaluru, tells us. The reasons behind the initiative were two-fold. “One was that here was a woman who in some sense lived a life ahead of her time, but her creativity had gone largely unrecognised. She is in the minds of certain people of her generation, but she remains out of our common vision because we don’t talk about her.”

The long-term goal of the project started by the family—Sinha and wife Kakoli Mukherjee, niece, Tapati Guha-Thakurta, and grand-niece, Mrinalini Vasudevan—was to build interest around a centenary exhibition later in the year, accompanied by talks, screenings and a publication, and eventually an archive. This would include memorabilia, including written notes, scripts, pictures, stills and her song recordings for Bharat Records and Hindustan Records, as well as recordings of her contributions as a voice artist for All India Radio. “She was in fact, invited by AIR to sing Tagore songs on the day Mahatma Gandhi was assassinated. That was a very moving moment in her life which she often spoke about,” Sinha tells us. Arundhati Devi’s first directorial film Chhuti for which she was conferred the National award for best film based on high literary work in 1967 has been restored by the National Film Archive and was one of the films screened last weekend to mark her birth centenary. “We would like to see if we can restore more of her films, not only for the unique sensitivity and creativity she brought in, but also as a woman director, actor, and singer who straddled different words of the media as well as a very difficult personal life. I think she is an interesting role model for women even today, who are striving to establish themselves in a patriarchal world,” shares her son.

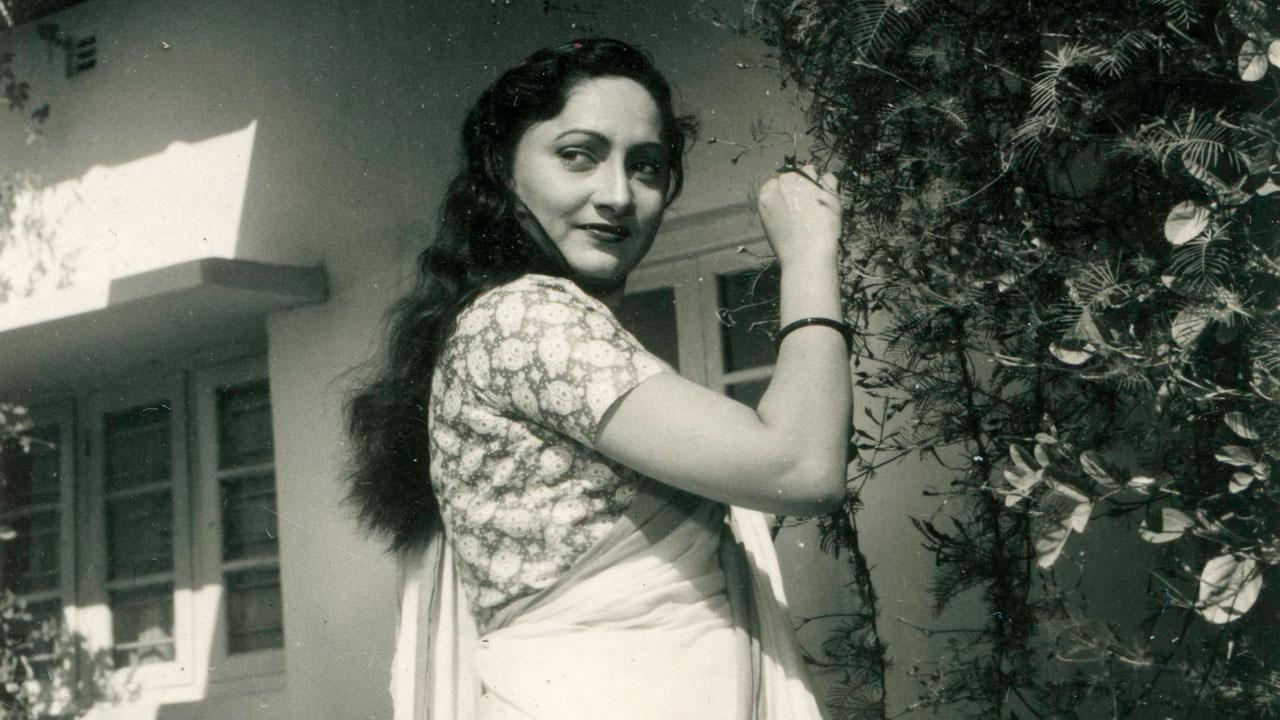

Chalachal, 1955. She starred in major and minor roles across 35 films, and came to be known for her layered performances and for championing the gaze and gait of a modern woman. Pics Courtesy/The Arundhati Devi Family Trust and Gallery Rasa, Kolkata

Chalachal, 1955. She starred in major and minor roles across 35 films, and came to be known for her layered performances and for championing the gaze and gait of a modern woman. Pics Courtesy/The Arundhati Devi Family Trust and Gallery Rasa, Kolkata

Mrinalini Vasudevan shares that since the initiative has been entirely family-funded thus far, they have had to work with limited resources and budgets. Films like Indradhanu, Panchatapa and Kalamati, are not to be found. Others like Nabajanma and Shiulibari are in poor condition, possibly because they were recorded from DVDs; they are unfit to watch on a big screen. There was also the challenge of tracing producers and rights holders, especially for institutions which have ceased to exist or changed multiple hands. “So, even while we wanted to have a variety of films to choose from for the Nandan screenings, our options came down to a handful.” She also speaks of the dearth of organisations and cinematheques that work towards preserving older films or back smaller independent non-commercial projects, and feels retro film festivals, like those of Film Heritage Foundation, may help build popularity around such initiatives. “Restoring and re-screening old films may be a good way of reviving the movie-hall business, and archival projects like ours hope to feed into or off this impetus.”

What the family has succeeded with is digitising 200 images from Arundhati Devi’s personal collection stored in her New Alipore home. “It helps that the actress, and her late daughter, Anuradha, arranged and labelled many of them, and we have much to gain from this careful documentation,” Vasudevan notes. Anindya Sinha however, shares that the meticulous preservation on the actress’s part was not necessarily driven by a desire to be remembered. “She was very clear that she was doing this collection, saving the material meticulously, only because she felt that’s how she should lead her life. I don’t think it mattered to her what happens afterwards. She never told me that she would like some of this to be saved, some of this to be published. It is also important to say here that she never did any autobiographies of her life.”

Samik Bandyopadhyay, Madhuja Mukherjee, Anindya Sinha. (Pic Courtesy/MD Madhusudan); Mrinalini Vasudevan

Samik Bandyopadhyay, Madhuja Mukherjee, Anindya Sinha. (Pic Courtesy/MD Madhusudan); Mrinalini Vasudevan

Cultural critic Samik Bandyopadhyay who delivered the inaugural lecture before the screening on the first day and who was known to both, Arundhati Devi and her filmmaker husband Tapan Sinha also speaks of the actress’s withdrawn personality, a fact that partially explains the scant attention her life and career has received. Pointing to her training in dance and music at Rabindranath Tagore’s Vishwabharati University, he draws attention to the fact that in the early 1950s the first generation of academically trained, enlightened actresses started coming on the scene for the first time in Bengali theatre and cinema. “So, there was a kind of resistance from the industry itself, [an uncertainty about] how to deal with them, how to manage them. They were kind of a threat. They came in with a knowledge bank, with an intelligence bank, [signalling a different scenario from] the way the actresses had been used, exploited, managed over the years in the professional theatre, in the professional cinema.”

At the same time, Bandyopadhyay also directs some of the responsibility towards his own generation of film historians. “The ‘50s and ‘60s was also the period when our great trio—Satyajit Ray, Mrinal Sen, Ritwik Ghatak—appeared on the scene,” he notes. “For a young generation coming into the world of thought, knowledge and maturity, being exposed to something like that…we developed a kind of contempt or withdrawal as regards the earlier Bengali cinema. We fell into this trap, and later on, I often felt that we should have taken a more historical look… If I had watched those films closely, even the “commercial” films that Arundhati Devi was doing… We rejected them in a way, and whatever time we had, we were opening up to the great changes in the European film or even other Asian countries like Japan.”

Filmmaker, media-artist and professor of Film Studies at Jadavpur University, Madhuja Mukherjee speaks of the absence of the histories of women professionals because of the condition of the film industry in India and elsewhere. “There are hardly any women in the film industry because of the nature of the capital, the way it is controlled, the industrial structure and how the great authors were built, imagined and circulated. It is a systematic marginalisation, not by one person. So people do not know, people do not care and people have forgotten.” She relates how while working on a documentary on contemporary film work with a special focus on women, she interviewed Juhi Chaturvedi, Kiran Rao and Suhasini Mulay and was looking for photographs of them working. “There are these images of the hand stretched out like a frame or of [Satyajit] Ray pointing towards something… you will not find any photos of that sort taken of women filmmakers, even now with images going viral and circulating so much.” She speaks of her own experiences with her film Deep6 and the stills that were taken behind the scenes. “They were mostly of me chatting with people or of me with puppies on the street. I had done so much work and I worked in various departments because it was a small budget film, but there wasn’t a single photo of me working.”

Mukherjee speaks of the importance of building archives, pointing to how the Bombay Talkies archive was not found with Bombay Talkies but with cinematographer Josef Wirsching’s family. “But even then, you will not find any pictures of Devika Rani working, say creating the costumes of the films. She was trained in textile design and was a professional and part owner of Bombay Talkies. A lot of work has been done in the last 10 years on women filmmakers. But those are not yet part of the curriculum, unless you are doing a gender studies course.”

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!