Dancer and choreographer Sameer Shaikh says bigots have made Islam seem homophobic, when it’s not

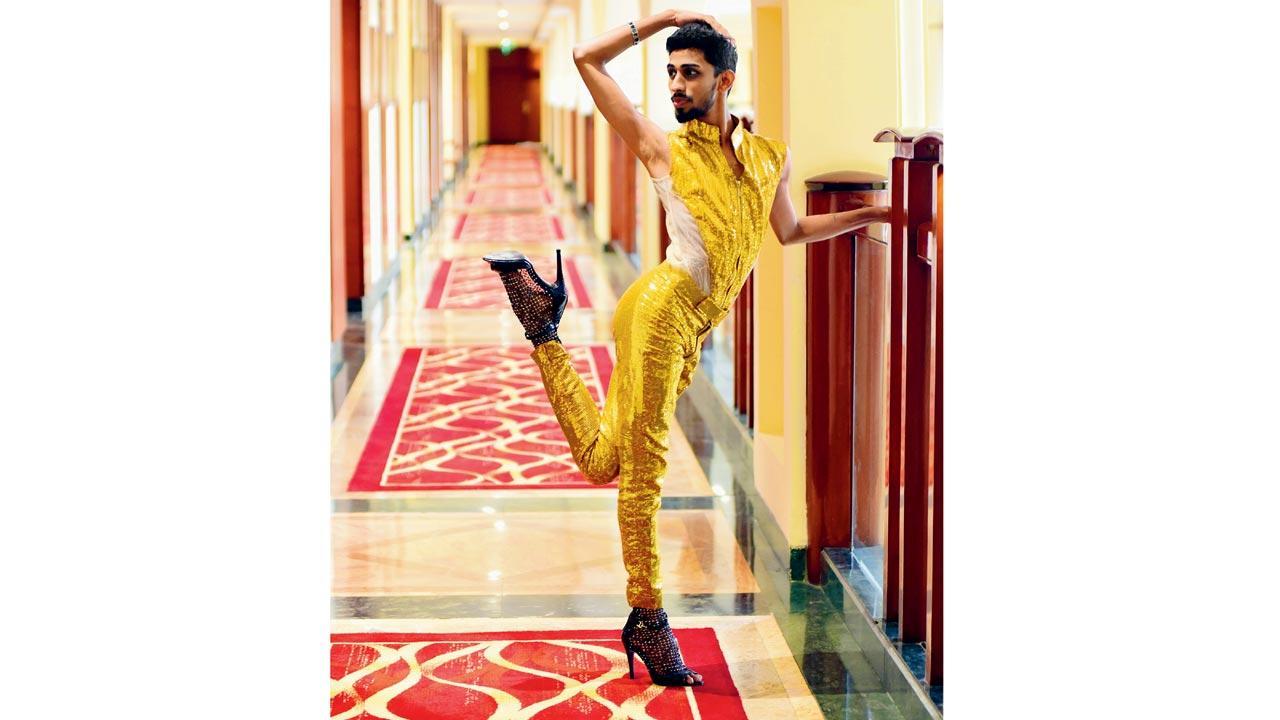

Sameer Shaikh, at LaLit before his performance. The dancer credits Inder Vhatwar who recognised his talent and got him into big shows. Pic/Nimesh Dave

Sameer Shaikh is trained in all styles of dancing, the choreographer paces around the room with a frenzied energy that takes some getting used to. He weaves in and out of the bedroom, playing with his palms throughout our interview on the seventh floor of The LaLit next to the Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj International Airport (CSMIA). He has a performance in a few hours at the hotel’s Friday evening marquee event for the LGBTQiA community—a haven for Shaikh, who came out to his family not too long ago.

ADVERTISEMENT

The 23-year-old grew up in the slums of Kalwa (where he still lives) and stops us short even before we ask. “Yes, it was as bad as you think,” he says with a sweet smile, as if trying to cushion the news for us. “In our community, whenever someone shows effeminate traits, they are called aapaa-jaan (elder sister). This word has plagued me throughout childhood. The playground, school and the bathroom in it—were all scary spaces as I was often cornered there and bullied.”

In Class IV, after summer vacations at his maternal grandmother’s home in Hyderabad near Charminar, he refused to come back home due to the abuse and harassment. To tempt him, his mother offered a trade: Come back and go to school, and I’ll let you learn dancing. “She knew I wouldn’t say no.” Shaikh’s mother unwittingly gave her son the most important tool to express himself from then on.

Learning dance for almost a decade at the Terrance Lewis Contempoary Dance Company and Nritya studio almost every day, Shaikh’s confidence grew with the grace the art gifted him. “At 18, I just blurted out to my parents that I am gay,” he says, “They were taken aback at first. For a few weeks, the whole house was quiet. After they processed the news, the family began to get concerned about sexually transmitted diseases—my mother asked whether I knew how two men get intimate; so did my brother.” They also asked how he would protect himself from STDs. “To be honest I had no idea, I only knew I liked boys,” he says, adding his father is more comfortable with his orientation now.

These questions led Shaikh on a path of self-discovery, and his first introduction to the community came in a local train compartment. A man approached him, introduced himself as gay and asked whether he was too, “Even though I was scared at first, I told him I am.”

The man took him to his first LGBTQiA+ party, and later to a hotel room, “When I refused to have sex with him, he threw me out at 3 am. I slept the whole night at Lower Parel station,” he says. “I was so scared and desperate that I downloaded Grindr to find anyone I could stay with for the night, but the men were very weird. I quickly dropped the idea.” In the morning, he caught the first train home.

Meanwhile his parents were still grappling with the news of his sexuality. “We have names for ourselves within our queer friends—I’m Samantha,” he says, “I would often announce at home that I want to be called Samantha, and one day my Abbu called me that playfully. That’s when I knew my family would come around, but my community is not so patient.” Shaikh has an elder brother and sister, who both support and protect him whenever he makes his way out of the bylanes of Kalwa to the railway station. His shows and dance classes are how he earns a living, after he abandoned education before HIS Class XII Board exams.

Shaikh is very much still a believer. “People have made Islam homophobic. Allah tells us to love and respect one another, but at this stage in my life, my parents are my God. My father is a building contractor and my mother used to work as a house-help, but they have opened their hearts and minds for me. I am the youngest, maybe that’s why,” says.

Shaikh’s physical expression of devotion was cut short as a child. “Whenever I went for namaz people would stop me,” he says. “Once, someone punched me in the back and laughed when I turned around. So my relationship with God was cut short. [Even now] During Ramazan, if I go to the masjid, I am constantly watching my back. Sometimes I am so anxious that I leave even before I enter the masjid.” But then, he adds, “God is always waiting back home for me.”

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!