What’s it like to be old and imprisoned in India? Latest statistics on medical care available inside Maharashtra’s jails paint a familiar, worrying picture

Girgaum residents Ashwin Parikh, 90, and his wife Vimla, 85, who were incarcerated for allegedly sexually assaulting a three-year-old neighbour, were released on April 11 from Yerawada Central Jail in Pune. The couple’s daughter says during their time in prison, they avoided using the common toilet due to its unhygienic conditions and having to wait in long queues, which affected their health. Pic/Pradeep Dhivar

Mane aiyathi kaadho,” is the repeated request that relatives of Ashwin Parikh and his wife Vimla remember from the time they would make a visit to Mumbai’s Arthur Road Jail and Byculla Women’s Jail respectively, where the two were lodged.

ADVERTISEMENT

Girgaum residents, Ashwin, 90, and Vimla, 85, were convicted on March 11, 2021 by a special court and sentenced to 10 years imprisonment for allegedly sexually assaulting a three-year-old neighbour in 2013. On April 8, 2021, the Bombay High Court released the couple on bail, after the court found inconsistency in the statements of the complainant, other witnesses and basis the evidence produced. The couple, who continue to claim that this was a conspiracy to usurp their south Mumbai home, was released on April 11 from Yerawada Central Jail in Pune, where they were shifted from Mumbai, said Advocate Dinesh Tiwari, who got them out on bail.

A protester adjusts a portrait of poet-teacher-activist and Elghar Parishad accused Varavara Rao on the face of another protester during a demonstration in New Delhi, following his arrest in 2018. Rao’s advocate Anand Grover had highlighted the dismal conditions inside Taloja Jail, before a division bench of the Bombay High Court, in April this year

A protester adjusts a portrait of poet-teacher-activist and Elghar Parishad accused Varavara Rao on the face of another protester during a demonstration in New Delhi, following his arrest in 2018. Rao’s advocate Anand Grover had highlighted the dismal conditions inside Taloja Jail, before a division bench of the Bombay High Court, in April this year

“No medicines were allowed in prison and they seldom used the common toilet due to its unhygienic condition and long queues. This affected their health,” says their daughter requesting anonymity. A relative told this writer that the family was unsure how to get prescribed medicines across to the senior citizens and were spending hours waiting outside the jail for the daily 10-minute mulaquat or official meeting time between prisoners and families.

“At a time when others their age spend their days praying, my parents continue to live in fear; they are shaken and have not got over the fact that they were imprisoned. They seldom speak now and don’t eat properly. Both can’t stand for long without support; the doctors recently treated my mother for a dislocated shoulder and her vision has failed in one eye.”

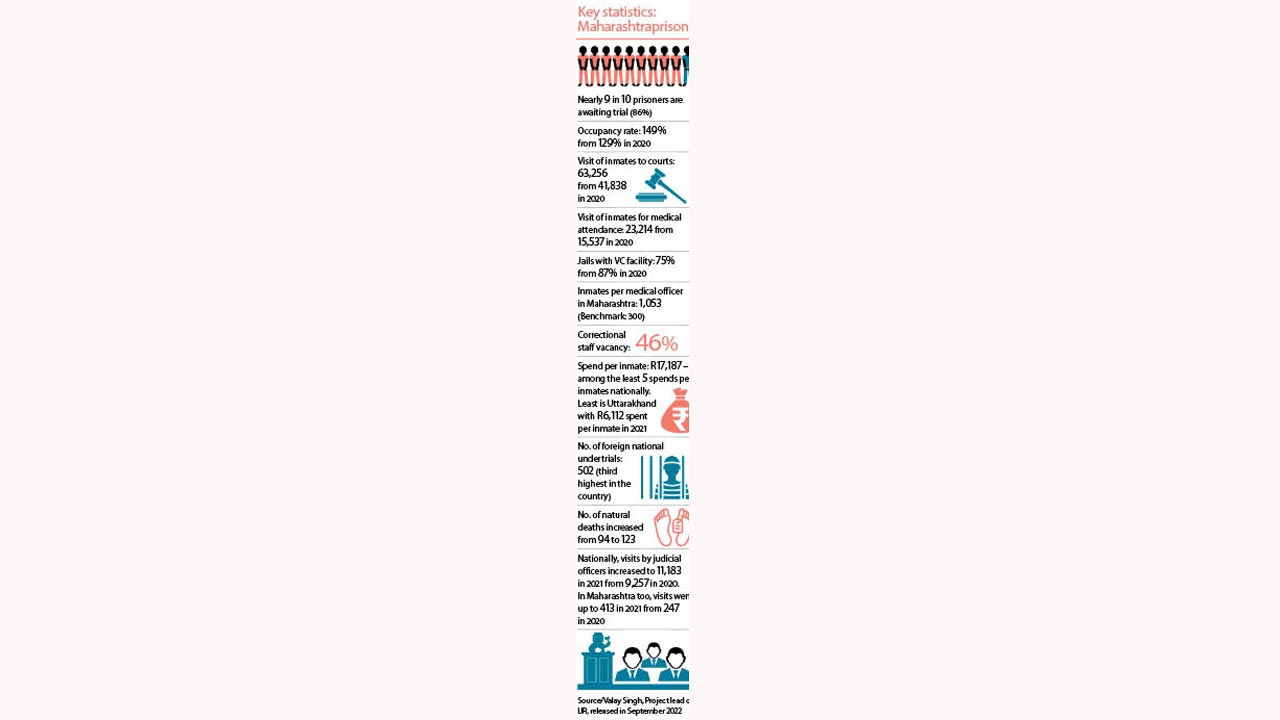

The near to no-access medical care inside Indian prisons is confirmed by recent statistics. While across India, visits by medical personnel to prisons had increased from 20,871 in 2020 to 22,015 in 2021, in Maharashtra, they had dropped from 2,136 in 2020 to 728 in 2021—a sharp fall of 193 per cent, according to Prison Statistics India, 2021, by National Crime Record Bureau (NCRB), Government of India.

Gujarat Anti-Terror Squad detained activist Teesta Setalvad on June 25, 2022. The Supreme Court granted her interim bail on September 2 in a case of allegedly fabricating evidence to frame innocent people in connection with the 2002 Gujarat riots. In interviews, she has highlighted the condition of Indian jails. Pics/Getty Images

Gujarat Anti-Terror Squad detained activist Teesta Setalvad on June 25, 2022. The Supreme Court granted her interim bail on September 2 in a case of allegedly fabricating evidence to frame innocent people in connection with the 2002 Gujarat riots. In interviews, she has highlighted the condition of Indian jails. Pics/Getty Images

Another recent instance of the dismal conditions inside the state’s jails, including overcrowding, lack of sanitation and basic medical care, came to light before a division bench of the Bombay High court in April 2022, which was hearing the medical bail plea of poet-teacher-activist Varavara Rao, 81, accused in the Elghar Parishad case of 2018 who was lodged in Taloja Jail of Raigad district.

The court had directed the Inspector General (Prison) to ensure that the Maharashtra Prisons (Prison Hospital) Rules, 1970 were being complied with. Senior Supreme Court Advocate Anand Grover, who represented Rao in both, the Bombay High court and the SC, said, “Convicts and prisoners are not completely denuded of their fundamental rights at the door of the prison. And right to health is recognised as a fundamental right under Article 21 of the Constitution, putting the onus on the state to implement the same even inside prison. The Prison Manual emphasises the same by mentioning clearly the [required] number of doctors, nurses, laboratory technicians, etc. who must be posted inside a prison.”

Valay Singh, Suresh Chavan and Sameer Joshi

Valay Singh, Suresh Chavan and Sameer Joshi

The situation, he told mid-day, was common across Maharashtra’s prisons . “The moment he [Rao] was shifted to Nanavati [private hospital in Mumbai], his health improved. When back in Taloja, his health started failing again. The state of Maharashtra is morally and politically responsible for the health and life of every prisoner—undertrial, detenue and convict prisoner,” the senior advocate added.

Teesta Setalvad was back in the news last week when in a biting opinion piece on a news portal, the writer-activist out on bail after spending 63 days in Sabarmati Mahila Jail said, “The result is an unhealthy clutch of power held by the jail authorities and bureaucracy over the prison space that inept medico-legal professionals [doctors at hospitals meant to oversee and report health and other conditions] fail to breach... Conditions in several of India’s prisons are pathetic with zero or next to zero monitoring by committees statutorily required to do this job.” She makes a pitch for using house arrest as option against police and judicial custody where the prisoner’s age or health conditions leave them vulnerable.

Floyd Gracias

Floyd Gracias

Valay Singh, project lead of India Justice Report (IJR), has been reporting on justice delivery in India. The IJR is brought out by a collective of organisations working towards justice reforms, including Centre for Social Justice, Common Cause, Commonwealth Human Rights Initiative, DAKSH, TISS–Prayas, Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy and How India Lives. The latest analysis of the Prison Statistic India-2021, by IJR was released in the second week of September this year. “The average spend per prisoner has gone down from Rs 41,319 (2020-21) to Rs 38,028 (2021-22) ie R104 a day per prisoner [expenses on inmates/total inmates as on December 31, 2021]. As of December 2021, 16 states/UTs spent below Rs 100 a day per person. These include 10 large and mid-sized states,” he adds. While the SC had shown proactive insight and taken measures to decongest prisons during the COVID-19 pandemic, Singh thinks the measures need to continue if we are to see prisons become places of reform. “Only a holistic approach can ensure that prisons don’t remain overcrowded, understaffed and perennially under-funded.”

Singh agrees that the most worrying statistic here is the overall decline in medical staff visiting prisons, including doctors, laboratory technicians, pharmacists and compounders. Vacancies went up from 32.7 per cent (Dec 2020) to 40.5 per cent (Dec 2021). Fourteen states have more than 40 per cent vacancies, with Goa (84.6 per cent), West Bengal (66.8 per cent), and Karnataka (61.3 per cent) recording the highest levels.

Nationally, medical officer vacancies stand at 48 per cent, which means one in every two posts has not been filled. There are 658 medical officers in Indian prisons to serve 5,54,034 inmates. On an average, this means each medical officer is supervising 842 inmates. The Model Prison Manual 2016 requires that there is one medical officer for every 300 inmates. In Maharashtra, one medical officer looks after 1,053 inmates.

Uttarakhand, with 6,921 inmates across 11 jails, recorded only one doctor against 10 sanctioned posts. With the exception of Andaman and Nicobar Islands, Arunachal Pradesh, Delhi, Manipur and Meghalaya, no state or Union Territory has reached the benchmark listed by the Manual, says the report.

According to data accessed from the State Home Department (Prison), sources revealed that Maharashtra has a total of 60 prisons, including nine central prisons, 19 open prisons and 42 district prisons. Together, they can accommodate 24,700 inmates and convicts; the present number of inmates (male and female) stands at 42,577, which includes 8,249 convicts, 34,117 under trials and 211 detenues.

For all of them, the prisons have a staff of just 5,068, including prison superintendents, jailors, wardens, guards and clerical staff.

Approximately 600 prison staff vacancies at different levels are yet to be filled. The state prison is headed by an IPS officer of the rank of Additional Director General and assisted by five DIGs (Correctional Service). At present, four crucial supervisory posts are lying vacant, which includes the Inspector General and Additional Director General of Police (Correctional Service), Deputy Inspector General (DIG) (Correctional Service) Headquarter, Pune, DIG, Aurangabad, and DIG, Nagpur, shares DIG Prisons (retired) Suresh Chavan, who was one of five members in a high-level committee appointed by the Bombay High Court under the chairmanship of Retired Justice Dr S Radhakrishnan for prison reforms; recommendations made by the said committee are yet to be acted on. “It’s not easy to work in a prison environment amidst habitual criminals and first time offenders. The Director of Health Services is to ensure that vacancies of health staff are filled. My experience has shown that doctors who get shortlisted for prison duty are not keen to work in that environment and end up opting for a transfer,” he adds, suggesting that the government upgrade the rank of DIG (Prisons) to Additional IG (Prisons). “And implement the recommendations of the Radhakrishnan Committee Report,” Chavan said.

As per Maharashtra specific data available with mid-day, of 44 sanctioned posts of doctors (MBBS and BAMS), only 33 are filled. Insiders reveal that nearly 30 prisons (district prisons) have visiting doctors, and most are general physicians. Of the sanctioned posts of five psychologist, three are vacant, there are five of nine laboratory technicians, and 32 of 47 pharmacists.

“The Constitution of India, under Art. 21, guarantees the Right to Life and Personal Liberty [and the protection from deprivation thereof], of all persons. Prisoners, whether convicts or undertrials, are persons within the ambit of Art. 21. While they may have committed or are being tried for the committance of an offence, they are still entitled to basic healthcare facilities. Criminology and penology over the years has changed schools of thought from earlier notions of punitive to the more recent constructs of reformation. Hence, it is imperative to focus on the health of undertrials and prisoners,” thinks Floyd Gracias, counsel, SC.

The other pain point, experts say, is overcrowding. Yerawada central Jail in Pune has a capacity to lodge 2,000 prisoners, although it lodges 7,000 prisoners (undertrials and convicts); Arthur Road Jail’s capacity is 800 and it houses 3,500 prisoners; Taloja has over 4,000 prisoners. “It’s no surprise that the infrastructure is already stretched. Nagpur Jail has a capacity to house 1,600 prisoners against the 3,000 it currently lodges,” a jail official told mid-day on the condition of anonymity.

What’s worse is that nearly 1,641 inmates continue to languish in various prisons across the state since they were unable to arrange for the surety bond after receiving bail. “There can be no doubt that a large percentage of the inmates of our jails today, is constituted by undertrial prisoners. Jails should primarily be meant for lodging convicts and not for housing under trials, if this is followed, the entire prison will get decongested. Moreover this was even recommended by the Law Commission of India, in its report on overcrowding of jails, but unfortunately, things remain the same, even today and the number is only increasing with every passing day,” said the jail staff.

3 Questions with Maja Daruwala

‘Local medical colleges must collaborate with nearby prisons’

Maja Daruwala, chief editor (IJR), senior advisor, Commonwealth Human Rights Initiative, takes mid-day’s questions

Why are medical personnel reluctant to visit prisons in Maharashtra?

The problem of shortfall of medical personnel is not restricted to Maharashtra. There are other states that are worse off. Across India, there is a shortage of doctors; who don’t easily opt for government service.

The responsibility lies with the judiciary and prison authorities to ensure that there is adequate money, equipment and personnel to prevent outbreaks of contagion, treat chronic ailments and be prepared for emergencies. A part of the solution is train convicts and other longer term inmates in paramedic work and make them barefoot doctors, who can treat simple ailments and injuries, counsel and give advice, teach better hygiene to others, etc. Attention also needs to be paid to improving health and medical capacities of the resident staff. All this can be done in cooperation with local medical colleges. It is not expensive to do. Local medical colleges should be encouraged to work in cooperation with nearby prisons to improve preventive care at a minimum rate and diagnose inmates.

Implementation of prison reforms recommended in the Justice (Retired) Dr S Radhakrishnan chaired committee report is yet to happen.

Guidelines for the same have been issued and the Model Prison Manual follows international standards. But to turn this intent to action requires will to make a change. Telangana is an example of the right attention paid to prison reforms; they’ve introduced various skill and rehabilitation measures

for prisoners.

How can prisons be turned into reformation centres?

Legal aid [to those who can’t afford a counsel] has a huge part to play in decongesting prisons, but again, the performance is patchy and has not been tested against client satisfaction. At the same time, we saw how during the pandemic, states were able to act and decongest prisons. Efforts must be sustained if a better environment within prisons is to be created.

Turning prisoners into medical assistants

Mumbai-based think tank iTransformIndia launched a unique skilling prisoners initiative by training them as medical caretakers/care givers.

Sameer Joshi, founder chairman of the programme, launched the experiment at Nagpur Central Jail and Yerawada in Pune. “During the pandemic, we realised that by providing training to the youth from the marginal communities, we can assist them learn skills for a livelihood and help the healthcare sector, which is in severe need of trained hands.” The pilot programme was discussed with the DIG (Eastern Region) Swati Sathe, who saw it as an effective means of rehabilitation and self-reliance of prisoners. “We picked HSC pass undertrials and convicts, who were keen to undergo training in bedside care, which involved both online and practical sessions by experts. Once the shortlisting was done, we trained them in basic and advanced bed care management, including checking blood pressure, recording temperature, arranging bedding, recording of pulse and even cardiopulmonary resuscitation.”

At present the prisons pay Rs 100 per day to a skilled worker, Rs 75 to a semi-skilled person and Rs 50 to an unskilled worker, all convicts. The undertrials are not given any work. “We are using funds from our pockets for the sessions in both Nagpur and Pune, but we hope the government takes this forward so that we can expand the training programme to other prisons across the country,” Joshi says. He counts among his achievements a call he received from a senior citizen from Nagpur, who enquired about the training. “Her son was behind bars and she wanted him to take on the training programme. She requested us so that he could start a new life once out.”

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!