The government admits 25,000 marginalised students quit IITs-IIMs in five years. IIT-B announced fresh anti-discrimination guidelines. A hardened law, social audit for campuses, more SC/ST teachers—what’s going to solve caste hate in college?

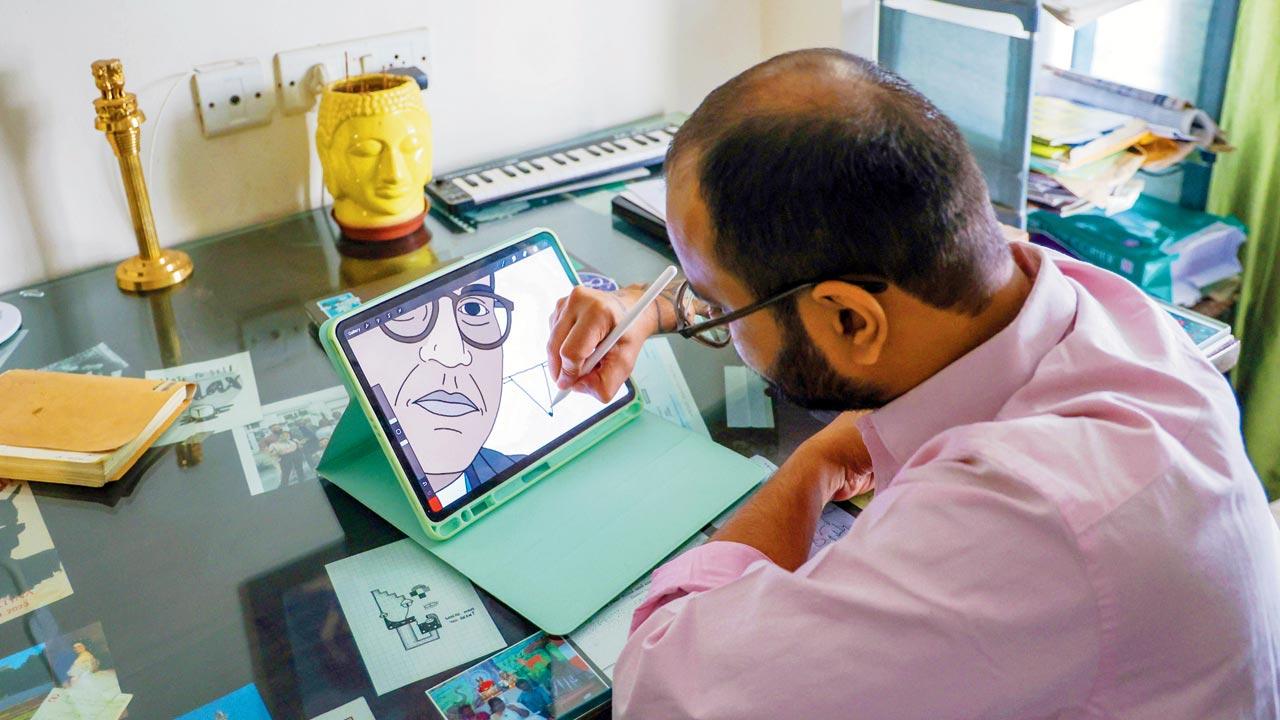

Noida-based multidisciplinary artist and proud Ambedkarite Siddhesh Gautam (@bakeryprasad) hid his caste to assimilate at Mumbai’s prestigious fashion and design school in 2010. It was only during a stint in Milan that he felt empowered to embrace his roots. His surreal and satirical work demands a caste-free world order. Pic/Nishad Alam

On Instagram, independent artist and Ambedkarite Siddesh Gautam’s illustrations reflect Dalit pride in blue. His handle @bakeryprasad has a deep-in-thought Dr Babasaheb Ambedkar in all avatars; the activism of Savitribai Phule, Jyotirao Phule, Ramabai Ambedkar, and Manyawar Dina Bhana, also inspires the 32-year-old’s artistry. This was not the case in his teens. “I was orphaned from history and forced to adopt someone else’s as mine,” he writes in an Instagram post.

ADVERTISEMENT

Now Noida-based, Gautam grew up in Bijnor in Western Uttar Pradesh and Uttarakhand, where his caste followed him like a shadow. “To protect me from this, my parents enrolled me in missionary schools,” he remembers. “I was unable to make friends, and had a lonely childhood,” he says over a call. When he got admission to the National Institute of Fashion Technology (NIFT) in Mumbai, in 2010, he thought he was finally starting afresh. “The institute didn’t have a hostel, so students were encouraged to rent an apartment with batchmates.” Gautam found himself in interesting company sooner than expected, and four of them decided to rent an 11th floor home in a Navi Mumbai highrise. “I remember the gentle, cool breeze from the window of that flat... I wanted to live there.” While they were in the midst of closing the deal, one classmate casually told the rest that although he was a ‘Kumar’, he was a Bhumihar Brahmin. “He initiated the conversation in a way that appeared like he was not asking us about our caste, but telling us instead.” Gautam realised that clarifications were in order. “But I was so mesmerised by the idea of living on the 11th floor that I decided to lie. One lie led to another... I even told them that my parents were vegetarian, that I was the first generation to try non-vegetarian food. That’s how, I ended up lying about my identity throughout college.” His new identity as a Brahmin also meant that he was now part of their close circle. “I learnt how they spoke about other classmates... they would take out answer-sheets and mark out the surnames that they found unidentifiable.”

Artist Siddesh Gautam says he was forced to hide his caste after he joined NIFT in Mumbai, because he didn’t want to feel alienated by other students. Pic/Nishad Alam

Artist Siddesh Gautam says he was forced to hide his caste after he joined NIFT in Mumbai, because he didn’t want to feel alienated by other students. Pic/Nishad Alam

While the institute itself propagated progressive ideas as an arts and design centre, the students, he says, had deeply internalised caste bias. “We would hear of students dropping out after a semester, but we never bothered to ask why,” he says, “There was no redressal mechanism in place.”

It would be many years later, while Gautam went on a semester exchange programme to Milan while pursuing his Masters at National Institute of Design (NID), Ahmedabad, that he came across people from cultures that he could associate with. “I met people who were not ashamed of their roots. They taught me to be reflective and vocal about it,” he says, adding, “I made my first Dr Ambedkar artwork in Milan. It’s here that I learnt that if I couldn’t find solidarity next door, I would find it 6,000 miles away.”

![Political analyst Anjali Kumbhar says within the reserved categories, caste hierarchies tend to play out. She remembers losing out to a Yadav student in the OBC category, who had scored 63 per cent. “I had scored 89 per cent, but the Yadavs are considered higher in the social hierarchy [within OBC category],” says Kumbhar; (right) Kripa Maria George, general secretary of the students union of the University of Hyderabad says following a report on discriminatory grading system in the institution’s PhD admissions, it was agreed that the person’s name and the category would not be made available to the panel interviewing the students. A separate committee would scruitinise the caste certificates, instead](https://images.mid-day.com/images/images/2023/aug/My-college-made-b_e.jpg) Political analyst Anjali Kumbhar says within the reserved categories, caste hierarchies tend to play out. She remembers losing out to a Yadav student in the OBC category, who had scored 63 per cent. “I had scored 89 per cent, but the Yadavs are considered higher in the social hierarchy [within OBC category],” says Kumbhar; (right) Kripa Maria George, general secretary of the students union of the University of Hyderabad says following a report on discriminatory grading system in the institution’s PhD admissions, it was agreed that the person’s name and the category would not be made available to the panel interviewing the students. A separate committee would scruitinise the caste certificates, instead

Political analyst Anjali Kumbhar says within the reserved categories, caste hierarchies tend to play out. She remembers losing out to a Yadav student in the OBC category, who had scored 63 per cent. “I had scored 89 per cent, but the Yadavs are considered higher in the social hierarchy [within OBC category],” says Kumbhar; (right) Kripa Maria George, general secretary of the students union of the University of Hyderabad says following a report on discriminatory grading system in the institution’s PhD admissions, it was agreed that the person’s name and the category would not be made available to the panel interviewing the students. A separate committee would scruitinise the caste certificates, instead

Last week, the Minister of State for Education Dr Subhas Sarkar informed the Rajya Sabha that a total of 25,593 reserved category students from the Schedule Castes (SC), Schedule Tribes (ST), Other Backward Classes (OBC), and other minority groups had dropped out of central universities and the Indian Institutes of Technology (IITs) over the last five years (between 2019 and 2023). Of these, 17,545 students were from central universities and 8,139 had dropped out of IITs.

And yet, several educational institutes continually deny and reject the existence of caste-based discrimination, says Professor N Sukumar, who teaches political science at the Delhi University. The alleged suicide of 18-year-old IIT-Bombay student Darshan Solanki in February this year is a case in point. While the family claimed that there was overwhelming evidence to show that Solanki had faced caste discrimination, an internal inquiry committee in its interim report had ruled it out. His deteriorating academic performance was claimed to be “a very strong reason”. But according to reports, in the chargesheet, Solanki’s mother told the police that her son had confided in her about the behaviour of fellow students.

N Sukumar, professor, Delhi University

N Sukumar, professor, Delhi University

Professor Sukumar’s recently-published book, Caste Discrimination and Exclusion in Indian Universities (Routledge)—the result of several years of ethnographic research—reflects on the fragile social world in which students from the margins struggle to survive in the academic space. “I began my research around 2008, when [28-year-old] P Senthil Kumar, a research scholar at the University of Hyderabad, died by suicide,” he shares over a call. “His body was discovered only 48 hours later. Until then, nobody was even bothered about what had happened to Senthil Kumar. It was at the same hostel where I had lived, when I was in university. I decided to write a paper, locating myself as a subject.” However, when he presented the paper in DU, he was accused of “valorising a non-existent issue”. “As a first-generation learner, who had experienced caste-based bias in the classroom, I felt an academic responsibility to prove that this wasn’t true, but with substantial data.” His research, which was supported by the Indian Council of Social Science Research (ICSSR) began in two phases. “In the first phase, I studied four universities, but I realised there were several gaps in it.” In the second phase, he tried to minutely map 10 universities across India—five state and five central universities, with 412 male respondents and 188 female respondents. “He segregated the respondents on the basis of gender, their discipline, and degree of education they were pursuing [Master’s, post doctorate etc].” He deliberately chose to keep names of the universities anonymous. At 32.60 per cent, caste emerged as the most common factor of discrimination in all the institutions, followed by language and ideological background. Sukumar’s study drove the point home—caste-discrimination in universities was for real. The question that needed addressing was what was being done.

According to Sukumar, caste-based discrimination in colleges became a glaring issue post the implementation of the reservation policy for “socially or educationally backward classes” by the Mandal Commission in 1990. While its implementation met with widespread protests, it also led to political vibrancy, giving birth to Dalit and Ambedkar student union bodies across the country. “This is also the time when first-generation Dalit teachers entered into educational spaces,” he says. “Students started demanding implementation of the reservations, but the outcome was not happy. The dominant caste categories saw this as a threat, and tried suppressing these movements. More so, they started practising discrimination, both openly and subtly,” adds Sukumar, who himself was the founding member of the Ambedkar Students Associations at the University of Hyderabad in 1993.

Dr Shailendra Deolankar

Dr Shailendra Deolankar

Back in 2016, brother-sister duo Priyanka Pandey, an economist and lead consultant with the World Bank, and academician Sandeep Pandey, who has taught at several IITs and is General Secretary of the Socialist Party (India), led a survey at the IIT-Banaras Hindu University, to show how caste affected students’ perceptions. “When we asked the students what they thought about the academic ability of those belonging to general category students, it was surprising that everyone from general category students, as well as OBC, and SC/ST students thought that it was ‘more than others’,” Pandey says over a call from the US. “What was surprising was that when we asked the same question on the academic ability of reserved category students, everyone, including SC/ST students said it was less than others. For me, that was a sad reminder about what we’ve done over the centuries. People who belong to the lower socio-economic category have also internalised this belief.” Sandeep feels newer ways of examining students could help address the issue.

mid-day tried reaching out to students from some of the city’s premier educational institutions, but they refused to come on record, fearing disciplinary action by authorities. A member of the Ambedkar Periyar Phule Study Circle (APPSC) at IIT-B says caste discrimination begins before getting into any of the IITs. “Who can get into IIT is also defined by who is inside IIT,” the student shares. He points to RTI data of students getting into PhD programmes at IIT-B—“the percentage of general category students getting admission into PhDs is 73 per cent, while the mandated percentage is 50.5 per cent; for OBCs it is 27 per cent, and SC/ST it is 22.5”. The national average of all 23 IITs is similar.

Prof Avatthi Ramaiah, dean, Equal Opportunity Centre, and liaison officer of the SC/ST cell at Tata Institute of Social Sciences, says for the last 15 years, the institute has been conducting a pre-admission orientation, in order to prepare OBC and SC/ST candidates to apply for admission. Pic/Pradeep Dhivar

Prof Avatthi Ramaiah, dean, Equal Opportunity Centre, and liaison officer of the SC/ST cell at Tata Institute of Social Sciences, says for the last 15 years, the institute has been conducting a pre-admission orientation, in order to prepare OBC and SC/ST candidates to apply for admission. Pic/Pradeep Dhivar

Faculty representation, he says, reveals a scarier picture.

“Ninety-three per cent are from general category, and five per cent from OBC/SC/ST... that’s a scarier picture.” “It’s this faculty that is responsible for selecting the students for PhDs.” According to him, at the admission process itself, there is a mechanism to push away students who are coming from reserved categories. Apart from the scores, they have another screening mechanism, which includes the written test, followed by the interview process. “In the interview, you are judged on the knowledge you possess, but also presentation and communication skills... your personality, dressing, language, everything comes under the scanner. It becomes more a test of the person, than their knowledge.”

Even in the 45 central universities in the country, 85 per cent professors and 82 per cent of associate professors are from the general category, Education Minister Subhas Sarkar said in the Lok Sabha this week.

Earlier this year, the Ambedkar Students’ Association of the University of Hyderabad (UoH) produced a seven-page report on the “discriminatory grading system” in the institution’s PhD admissions. The report stated that despite having comparable admission exam scores, students from reserved categories were marked substantially lower than those from unreserved categories in interviews. Kripa Maria George, general secretary of the students union, UoH, told mid-day that following a five-day protest, the University agreed that the name of the person and the category would not be made available to the panel interviewing the students. “To ensure transparency, a separate committee will scruitinise the certificates of students in the reservation category; this committee won’t be part of this panel.”

According to APPSC member, the discrimination becomes more direct once students are admitted to the institution—you are asked under which category you got admission, or at a more subtle level, they ask about the cartoon you watched as a child, the literature and music you read, or the food you eat.

A Chennai-based medical student, who is currently applying for a Master’s in public health in the US, remembers that when she was pursuing her undergraduate degree, her HOD casually enquired where she hailed from. “Since I am Christian and don’t take a surname, my identity markers are not clear. But the moment he learnt, his behaviour changed. He didn’t give me my practicals—I would get my final scores and degree only on the basis of the cumulative of the practicals and internals. I had to approach another professor to intervene,” she says, on condition of anonymity. The same HOD is now the principal of the college, and she says, he has been creating an obstacle for her to obtain certain transcripts needed to secure admission abroad. “I had spent my childhood in Saudi Arabia and the US, where I didn’t wear my caste on my sleeve. Here, I felt like a fish out of water. It made me bitter, angry, and lonely... I couldn’t vocalise how I was feeling. It followed me, and I ended up expressing it in the wrong places.”

Sometimes, even within the reserved categories, caste hierarchies play out. Like it did in the case of Hyderabad-based political analyst Anjali Kumbhar. While trying to get admission to a suburban college in Mumbai for a Bachelor of Mass Media degree, she lost out to a Yadav student in the OBC category, who had scored 63 per cent. “I had scored 89 per cent; I am from the Kumbhar [also known as Kumhar] community, and we are traditionally associated with pottery. Yadavs are considered higher in the social hierarchy,” says Kumbhar. “This didn’t occur to me, until I sat down to think about why I had lost out, despite scoring well.”

Earlier this week, IIT-B issued a fresh set of anti-discrimination guidelines—a move that perhaps, finally saw the institute acknowledge its former student Darshan Solanki’s plight. In his letter to the students, Suryanarayana Doola, dean of student affairs at IIT-B, stated that it’s “inappropriate” to ask other students about their JEE Advanced rank or GATE score or any other information that may reveal caste or other related aspects. The letter also stated that exchange or forwarding any message, including jokes that are abusive, hateful, casteist and sexist, were prohibited. In order to help the institute achieve an inclusive atmosphere, students have been asked to “bond over sports, movies, music, and hobbies”. “The efforts are too little, too late,” says the student from the Ambedkar Periyar Phule Study Circle.

To ensure the effective implementation of the reservation policy in admission, recruitment, allotment of staff quarters, hostels etc, the University Grants Commission has been encouraging establishment of SC/ST Cells in the Universities. An important function of the cell is to help SC/ST categories “integrate with the mainstream of the university community”. IIT-B formed an ST/SC students cell in 2017. “Before that, we had an SC/ST students faculty advisor,” the spokesperson told mid-day.

Professor Avatthi Ramaiah, dean, Equal Opportunity Centre, and liaison officer of the SC/ST cell at Tata Institute of Social Sciences, says for the last 15 years, the institute has been conducting a pre-admission orientation, in order to prepare OBC and SC/ST candidates to apply for admission. “Faculty and other experts come and talk to students about how to crack the entrance tests. We also share the facilities available for OBC, SC/ST students,” he says. “Once the students are admitted, we again have a formal orientation for all students, where we talk about the SC/ST cell, and how those violating the code of conduct in the TISS handbook, will be dealt with strictly,” he says. The guidelines are mentioned on the website, and the students can approach the Equal Opportunity Centre regarding any violation.

Dr Shailendra Deolankar, director of higher education in the Government of Maharashtra, said that institutions have already been made aware of implementing caste-based reservations. “We are also ensuring that constitutional provisions regarding caste-based discrimination are followed to the tee, including grievance mechanisms being made available to students,” he says. Deolankar says, according to protocol, if they receive such complaints, they reach out to the particular university to take appropriate action.

“So far, I have not come across such a complaint, but if the university concerned is not addressing this, students can directly approach me.”

Professor Sukumar, however, feels that a lot of work still needs to be done. “Until caste is not acknowledged as a problem and we don’t own it, we are not going to find solutions,” he says. The state, he says, needs to conduct a social audit across all campuses—public, private universities, medical colleges, IITs, IIMs—about policy-implementation and outcomes. “We should have at least a 10-year record of this, to help figure out why attendance is an issue among SC/ST candidates, or why are students feeling pressurised in competitive courses like IIT. Once we know the intensity of the problem, we can formulate policy-level solutions.” According to him, we need to “inculcate radical empathy, not sympathy”. “Just like the Ragging Act, we also need a criminally offensive act on caste discrimination.”

32.60

Percentage of people who said they were discriminated based on their caste, according to research carried out by N Sukumar

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!