A new book by researcher and member of the Gomantak Maratha Samaj that traces its roots to Bahujan women who served at temples and had Brahmin men as patrons, reflects on the earliest liberators of caste and sexual oppression

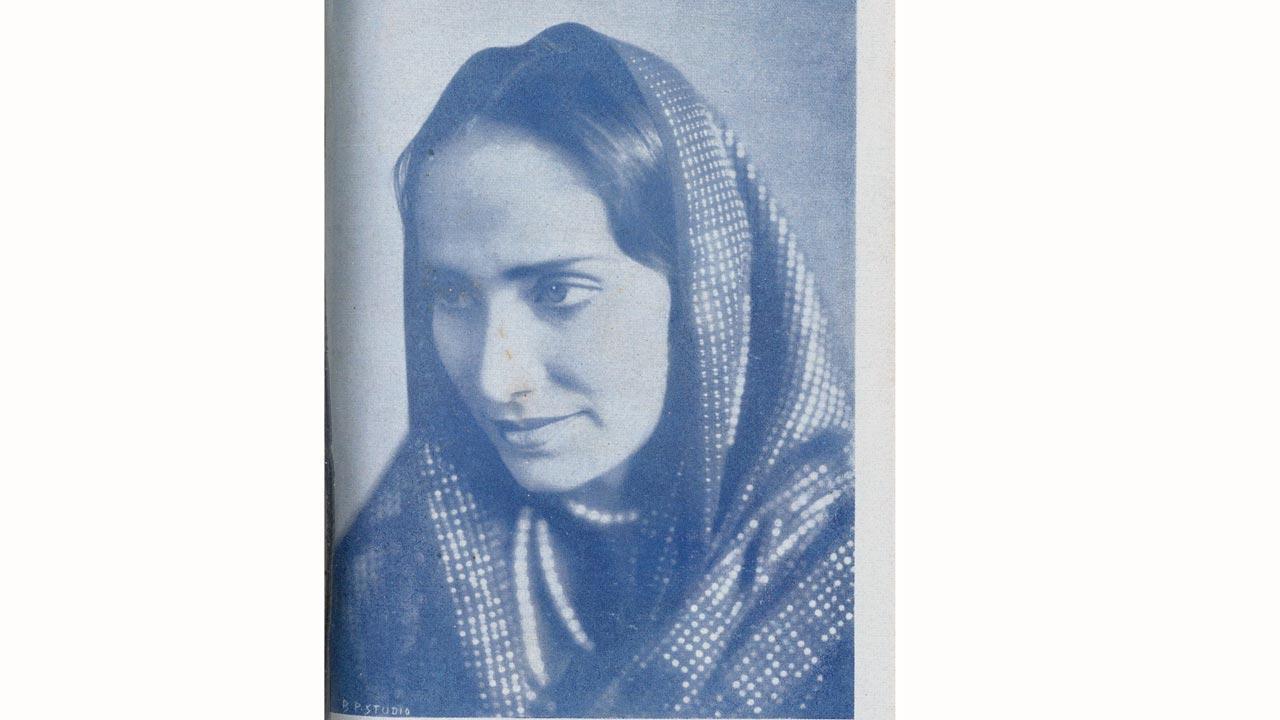

An anonymous woman of the Samaj, from March 1940 cover of Samaj Sudharak. Pic/Gomantak Maratha Samaj archives

When women from the Gomantak Maratha Samaj first arrived in Bombay in the 1900s, they were seen as a threat… as ‘evil ladies’,” professor-author Dr Anjali Arondekar tells us. Perceived as “cultural outliers”, people feared they would pollute the form and fabric of the traditional Hindu family. The reality, explains Arondekar, was different—women from the Samaj fiercely opposed their own exploitation, and in doing so, pushed formidable boundaries.

ADVERTISEMENT

The Samaj draws its members from complex groupings of Goan Devadasis, and traces its roots back to the early 19th century, when Goa was under Portuguese occupation. They were composed primarily of Bahujan women who served at temples, and had Brahmin men as patrons. While devadasis were often seen as interchangeable with courtesans and prostitutes, women from this group “were protected under traditional and colonial law for their attachment to temples”. “Unlike what might be expected of a sex worker in the traditional sense, they had both coercive and non-coercive monogamous relationships with mostly Brahmin, and sometimes non-Brahmin, men,” adds Arondekar.

Descendants of the community formalised themselves as a collective in 1927—its constitution was drafted in 1929; the Gomantak Maratha Samaj (GMS) has since continued to provide services, scholarship and outreach to over 10,000 members all over Goa, western Maharashtra and Karnataka.

Anjali Arondekar

Anjali Arondekar

Arondekar, who grew up in the Samaj, has committed her scholarship to understanding the multi-layered history of this caste-oppressed collective of devadasis from western India, and how they became advocates for their own liberation. In her book, Abundance: Sexuality’s History (releasing in India with Orient Blackswan), Arondekar dips into the archives of the Gomantak Maratha Samaj to centre sexuality and liberation within post-colonial histories. The Samaj, which she has spent nearly 15 years researching, is the window to this exploration.

Central to the Samaj’s self-definition was and is its eschewing of any relationship to its past. By the turn of the 20th century, some of them had begun relocating towards western Maharashtra and Karnataka, shedding their association with temples. They were given property by their Brahmin patrons. “The taxpayer association of Girgaum wanted these women evicted [as they were widely perceived to be courtesans],” Arondekar says.

But the women of the Samaj challenged the endogamous structure of society, which Arondekar says is one of the most important aspects of their legacy today. “Many women with Brahmin patrons gave birth to offspring who often took on their biological father’s surname. Such instances muddled the idea of a pure bloodline, making caste lineage increasingly unreliable.” The very existence of the Samaj and their children, hence, threatened to fundamentally alter ideas of caste in a society which was built on casteist hierarchies. Arondekar explains in her book, “In bypassing the mandates of endogamy, the history of the Samaj proffers a more radical or perhaps more chaotic caste narrative, one where there is no fixed inherited origin and where caste histories are always threatening to dissolve.”

Their role in changing perceptions of caste, however, is “not, as one would expect, aligned with other caste reform projects”. “This is a phenomenon I’m interested in: what happens when minority communities don’t behave in the way in which we want them to,” she tells mid-day.

“An uncomfortable truth for historians to reflect on,” says Arondekar, “Is that, in the history of the Samaj, and that of a lot of similar groups, the caste system was the main source of oppression—even more than colonial forces. There are people from the Samaj who, of course, participated in the colonial liberation movement, but more than the Portuguese, it was the Brahmins who exploited them.”

Both male and female members of the Samaj were constantly advocating for their freedom and maintained a thorough archive of their struggle. Since 1929, the Samaj, now a charitable institution, has published a monthly journal, the Samaj Sudharak, which covers topics such as caste, education, marriage and prostitution. “The Samaj is simply radical in that it sustained its own archive. There used to be a Samaj building in Girgaum close to where my family lived, which was a welcoming space of gathering and debate,” she says. “It was filled with the minutiae of Samaj life, such as the monthly Samaj Sudharak that began publication in 1929, and continues to this day. The Samaj Sudharak is now called the Gomant Sharda, and even as it has diminished in content, its production continues unabated.”

Among the more famous members of the GMS were the kalavants, who got their name because of their musical talents, and who, unlike devadasis, rarely wed deities and were not “prostitutes” in any conventional sense of the word. This group mostly comprised female singers, who were classically trained. Their move to Mumbai, then Bombay, coincided with the growth of the Hindi film and music industry in the 1930s and ’40s. “There is a very visible presence of the Samaj in the Hindustani community of musicians. This includes figures like Lata Mangeshkar, Asha Bhosle, Mogubai Kurdikar, and Kishori Amonkar.” According to reports, legendary Hindustani classical vocalist Pandit Deenanath Mangeshkar’s mother, Yesubai Rane, belonged to the Samaj. Despite his musical brilliance, Mangeshkar found himself at the periphery due to his caste, and was forced to leave his native Mangueshi in Ponda, Goa, early in life. While the family moved to Mumbai, they continued their association with the Shree Manguesh Devasthan. Lata Mangeshkar, in fact, served as a member of the Kala Academy in Goa.

While the Samaj is replete with extraordinary kalavants, Arondekar says it also comprises women “like my mother, my aunt, and my grandmothers, all of whom were both exceptionally ordinary and resolutely extraordinary in their desire to build, sustain and educate our community. So many people in my community, in my parent’s generation, had access to education only because their mothers and grandmothers in the Samaj worked to provide it for them.”

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!