Why did Sherlock Holmes’ creator support convicted son of Britain’s first ever South Asian vicar? Shrabani Basu’s new title unravels how race, class and sociological dynamics played out in one of the Empire’s most sensational cases of the early 20th century

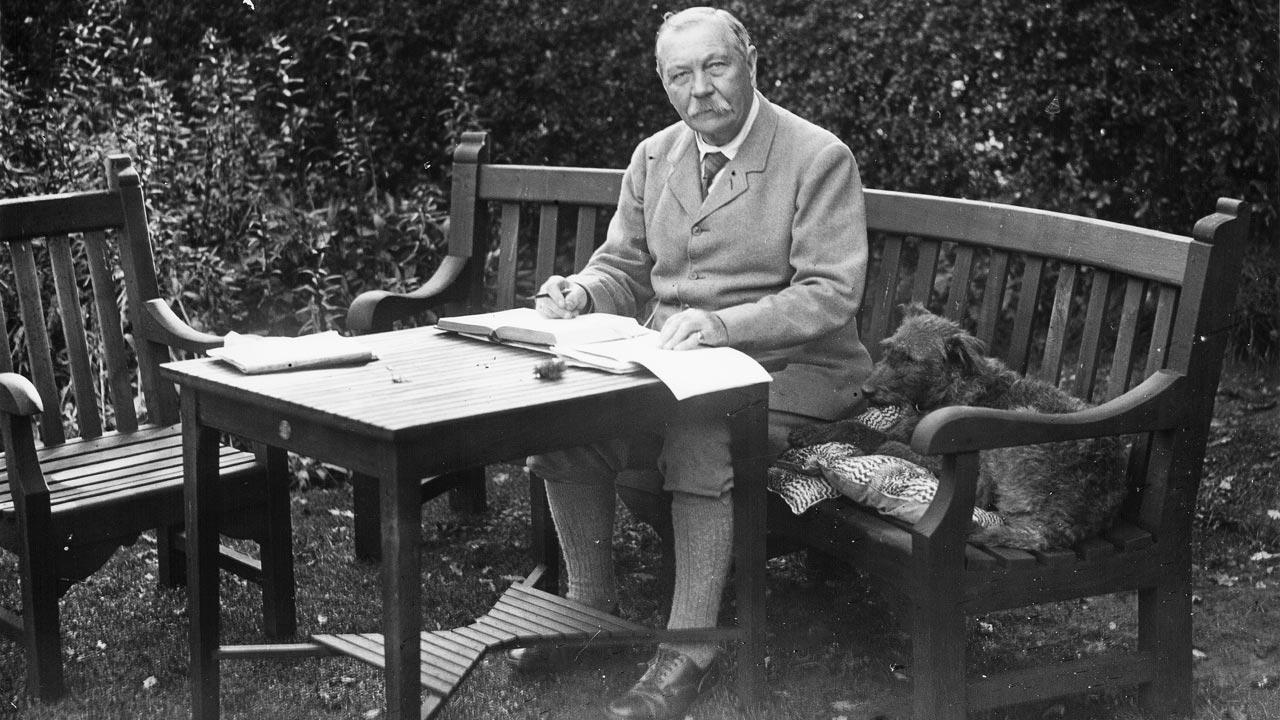

Portrait of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle sitting at a table in his garden, Bignell Wood, New Forest, in 1927. Pic/Getty Images

There is a section in The Mystery of The Parsee Lawyer: Arthur Conan Doyle, George Edalji and the case of the foreigner in the English village (Bloomsbury), where the first meeting between Sir Arthur Conan Doyle and Staffordshire’s police chief Captain GA Anson is explained in detail. It proves to be an eye opener for the intuitive author who has decided to back a studious Parsi lawyer who reaches out to him for help, having lost faith in the police and legal system, after completing a jail term. Their exchange reveals to Doyle the coloured mindset of authorities judging every Oriental, irrespective of upbringing, education and profession. Doyle takes up the investigation, and thus, a friendship develops between George Edalji, the ‘half-caste son’ of an Indian clergyman and his unlikely saviour, the highly respected creator of the Sherlock Holmes series.

ADVERTISEMENT

Shrabani Basu’s new book is the result of meticulous detail. The author says she travelled to the small parish village in Great Wyrley to retrace the nearly century-old saga, from the time the patriarch, Shapurji arrived in Britain in 1866 as a Parsi convert to Christianity; his elevation as the first South Asian vicar of an English parish; to when the needle of suspicion was cast over the Edaljis’ happy existence, first with mysterious letters and later, with gruesome murders of cattle and horses; how the case blew out of proportion with the imprisonment of the eldest son, George and its fadeout with the demise of Shapurji’s daughter, Maud in 1961.

Shapurji’s early life in Bombay is equally insightful: his days as an impressionable Elphinstonian who decided to follow the path of missionaries, and his rebellion and estrangement from his shocked Zoroastrian parents in 1800s Bombay as they faced their son’s decision to convert. The fighting spirit in young Shapurji was replayed years later, when he backed his wronged son despite societal pressure and a biased judiciary. He carried on with his pastoral duties, and backed George without moving out of his parish.

George Edalji with the St Mark’s Church, Great Wyrley, in the foreground. The Edaljis’ residential quarters were within the church compound, where his father Shapurji was the vicar. Illustration/Uday Mohite

George, who faced stigma for these dark crimes since he was a teenager, drew from his father’s resilience, and believed his honesty would prevail. Later, as the out-of-work lawyer, he wrote to his favourite crime writer, Conan Doyle to help clear his name and reputation. It was a masterstroke. Writers like George Bernard Shaw and JM Barrie (both friends of Doyle) backed George, too. Public perception changed overnight, thanks to Doyle’s investigation and newspaper articles. Soon, the case hogged headlines on both sides of the Atlantic, and George’s fate turned. Doyle’s exchanges with Anson, his unflinching support for George, and his own mental turmoil as creator of the world’s most popular detective, make Basu’s book read like a thriller created from Doyle’s own pen.

When she discovered George’s final resting place in Hatfield Hyde Cemetery in Welwyn Garden City, his gravestone was layered in thick undergrowth; perhaps, a symbolic reminder of the injustice that plagued a family that couldn’t break free from the shackles of prejudice.

Edited excerpts from the interview:

In 1868, at the meeting called by the Bishop of Oxford, Shapurji spoke in high praise of the English and the need to ‘save souls’ in India. Did he resent the country of his birth and education?

It was not so much resentment for the country of his birth, as for the religions practised there. He was clearly opposed to his own Parsi faith. He was an admirer of Ram Mohan Roy and believed in reformist religions and the Unitarian Church.

Shapurji knew that he would never return to India. He had left his family anyway, and knew it was almost impossible for him to be appointed a vicar in a church in India as these [positions] were always given to white people. England gave him the opportunity to widen his knowledge, which he valued.

Gravestone of George Edalji in Hatfield Hyde Cemetery, Welwyn Garden City

After the first phase of harassment faced by the Edaljis, how did Shapurji continue with his duties towards his parish?

I doubt he had a choice. He just kept his head down and carried on. Not everyone in the parish was racist, so he hoped it was one person or a small group.

It is very much the experience of Bangladeshi and Indian restaurant owners and shop-owners in Britain in the sixties and seventies, who had racist graffiti scribbled on their workplaces and material deposited through their letterboxes. They just cleaned the shopfront and carried on.

Despite being a baptised Christian, why was George’s Parsi origin constantly raked up in press reports and during the courtroom exchanges?

It was very much the culture of the time to refer to somebody’s ethnic roots. In court, the colour and the ethnic origin of the person in the dock and his ancestors was always referred to. This was all happening at the height of the Empire, and the Edalji family were definitely seen as subjects of the Empire. The media reporting of the case showed how much they made of George’s Oriental roots, and the religion of his ancestors.

Shrabani Basu

How was it possible for Sir Arthur Conan Doyle to write freely, without facing censorship in The Daily Telegraph articles?

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle was a highly respected figure, not just as an author, but as someone who went to South Africa and helped Britain during the Boer Wars. He would not have any problem publishing his work. The Daily Telegraph was delighted to publish it. They even made it copyright-free so that it could be reproduced freely by other papers.

For that matter, even George Edalji wrote about his experience in Pearson’s Weekly. There was no censorship at all. His story was seen as sensational and helped sell copies of the weekly.

Do you believe that the Oscar Slater case distracted Sir Arthur Conan Doyle from pursuing George’s case further?

No, he continued to fight for compensation for George Edalji, but gave up when he realised that the Home Office would simply not budge. Slater was an easier case. However, Conan Doyle did not investigate it. He simply pointed out the flaws

in the trial.

Did George suffer from mental health conditions as a result of his long-drawn ordeal with the law?

It would be terrible for anyone to go through what he did—racist abuse, prison term—without getting scarred. But he wasn’t a pushover. The fact that he wrote to Arthur Conan Doyle and carried on the fight for compensation all his life shows his stubbornness and staying power. He was quite particular that people pronounced his second name accurately, which shows he was not ashamed of his roots.

Did you know?

Jawaharlal Nehru was an 18-year-old student at Harrow when George’s case was being fought. He wrote to his father Motilal, suggesting that he was innocent and was convicted simply because he was Indian.

The German Connect

Shapurji Edalji met Orientalist Friedrich Max Müller in the UK. At his request, Shapurji published a translation into English of the Pandnamah, an ancient Zoroastrian work on morality, in which Müller penned a personal preface. It was an important moment for him to relearn the teachings of Zoroastrianism, a religion he had rejected as a youth, and appreciate its moral guidelines of truthfulness and charity.

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!