If anyone here is wondering why India’s brightest social commentators and political humourists are silent at a time when someone should be calling out absurd tragedy, it’s because they are figuring out the how (without getting jailed)

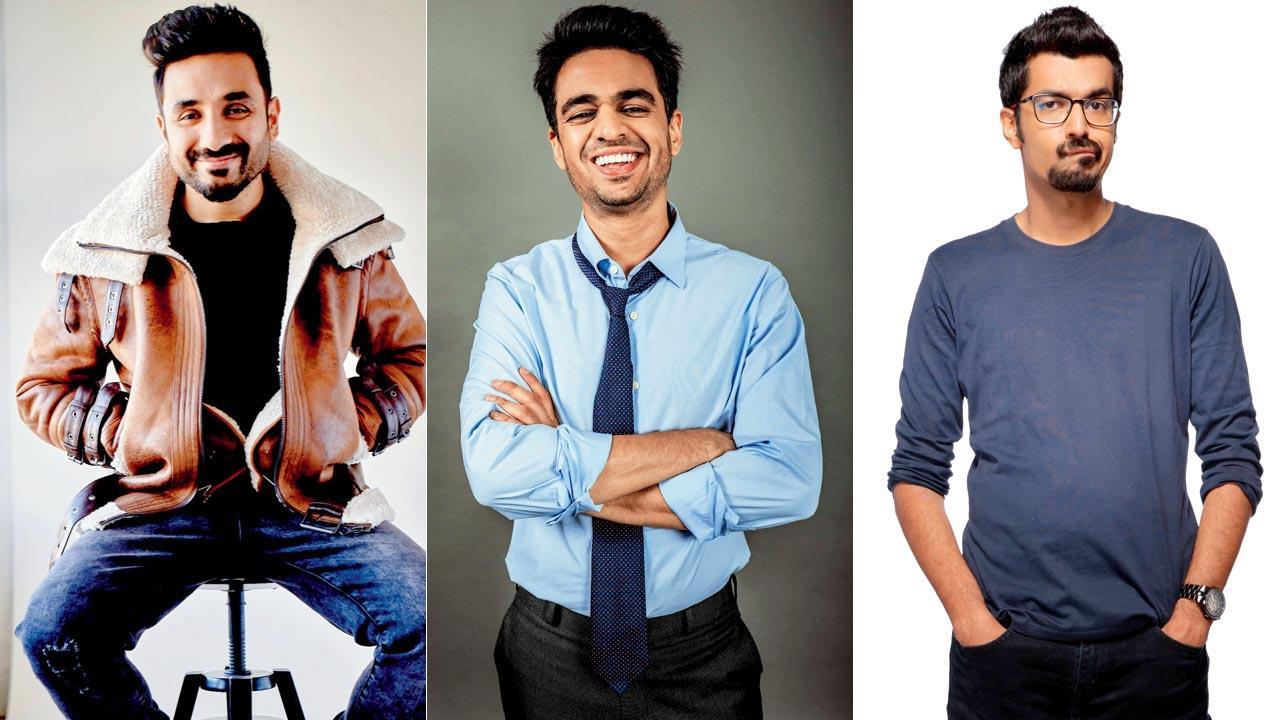

Vir Das, Rohan Joshi and Azeem Banatwalla

Last Thursday, Mumbai-based comedian Azeem Banatwalla put up an Insta story that announced a comedy special he is launching. He chased the announcement with a clarification: it would be heavily edited, and those who wished to watch the self-censored bits could get in touch with him, join him on a live Zoom session and pay to view.

ADVERTISEMENT

When Banatwalla started work on the special two years ago, the political climate of the country was different, he says. No OTT platform is keen to showcase it now, because it’s in English and addresses politics. “I thought why not then go pay to view. When you shell out cash, you show a certain investment in the content. It will come from those who are unlikely to be offended,” he reasons. Banatwalla tells mid-day plainly that he took a decision this year that he won’t push the envelope beyond a point. The consequences of calling a spade a spade in India range from horrific trolling to legal wrangle and even being slapped with Section 295A (deliberate and malicious acts, intended to outrage religious feelings of any class by insulting its religion or religious beliefs). “The message behind my edited special is that today in India, this is what comics have to do to get their work out. From now on, I will stick to social commentary. Religious and political discourse can affect my livelihood. I don’t want anyone to say, he makes a living by making fun of Hindus. I may speak my mind as Azeem, the person, but not as the comedian.”

Vir Das, whose new show drops on YouTube today, says at a time like this, he can’t do comedy without addressing imperative subjects

Balraj Singh Ghai, the founder of Khar’s live performance venue The Habitat, where Banatwalla’s special was shot, thinks it’s a way for comics to protect themselves. He says, “You would think that education makes people more empathic, but most audiences, even in the metros, are devolving into something horrible. A comic has no choice but to check himself.”

Which explains the silence from some of India’s biggest stand-ups on the Coronavirus pandemic, the crumbling health infrastructure, the country’s struggle with COVIDiots, the unscientific goop spewed by politicos that makes you want to say, what a joke!

Comedian Atul Khatri’s wife and daughters have also been attacked online, and his tweets have been morphed. Pic/Shadab Khan

The last one-and-a-half years have provided content fodder like no other time. The arbitrariness of the Citizenship (Amendment) Bill, the farmers’ protests against the Farm Bills, the Central Vista project at an estimated R20,000- crore that critics are calling out as an exercise in vanity, and of course, the central government’s hubris that has punctured India’s critical vaccination programme. Can the brightest, most successful humourists of India point a finger at Prime Minister Narendra Modi, who incidentally most of them refer to as “Supreme Leader” to dodge trouble, by bhakts online and worse, IRL (in real life)?

Muslim comic and Dongri resident Munawar Faruqui didn’t take long to become the toast of the town. The Junagadh boy didn’t shy away from making jokes about politics and his own Muslim identity.

Bhubneshwar’s Alokesh Sinha has only just managed to spring back from the attacks he faced last year from Right wing sympathisers, who protested against a joke on the Hanuman Chalisa. Pic/Rahul Sharma

In January this year, he was arrested in Indore, for a joke he hadn’t made. He was on a nationwide tour titled Dongri to Nowhere, when a Hindu organisation filed an FIR against him. He was released from jail 22 days later after the Supreme Court intervened. Faruqui has stepped back a bit since then.

His castigator claimed a new victim a week ago. Eklavya Singh, the son of BJP MLA Malini Laxman Singh Gaud, who heads the outfit, Hind Rakshak, called YouTube comic Ranjeet Bhaiyya, demanding that he remove a set about fasts observed by Hindus. He removed the set, but stands betrayed because even after doing so, they leaked the recording of the chat, online. “It felt like they were saying, ‘dekho, kaisa sabak sikhaya’. I am not angry, just deeply hurt. I am an Indore boy who has been trying to make it since 2015. If I do well, my state and the city look good. It seemed like they wanted to make an example out of me.”

Mumbai comic Azeem Banatwalla has decided to only focus on social commentary, and not comment on political or religious issues

In Bhubaneswar, Alokesh Sinha, 23, says he is experiencing relief after being the target of trolls for a year. After he performed a set at The Habitat, he was accosted by members of Bajrang Dal and the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh for referencing the Hanuman Chalisa. Tongue firmly in cheek, he had likened its powers to Dettol—effective only 99.9 per cent of the time. He was forced to release two apology videos before they promised to withdraw the police complaint, which they never did. He went underground. Sinha resurfaced this year, but says each time another comic gets called out by trolls, they also come back looking for him. “The creative process I now follow is this: I make a joke, and check with five of my comic friends if it’s offensive. We improvise and make changes. If it’s not the trolls, it’s fate.” The pandemic has robbed him of work. He is currently working with an IT company on a short-term gig. The occasional virtual standup show will continue. He shot for one last Friday at a Bhubaneshwar studio. Sinha rues, “Indians don’t hate comics—they hate comics who tell the truth. They say, ‘look at Kapil Sharma!’ They don’t mind his sexism. If I have to survive, or make money as a comic, I need to change my tactics, search

for a smarter way to present my material.”

And so, instead of finding an effective and empathetic way to write a set around the pandemic, comics are helping COVID patients find plasma donors.

After filing a police complaint against Mumbai comic Munawar Farooqui, Eklavya Singh, the son of BJP MLA Malini Laxman Singh Gaud, who runs a right-wing outfit named Hind Rakshak, attacked comedian Ranjeet Bhaiya (above) for taking a jab at the fasts that Hindus keep

A well-known female comic from Uttar Pradesh, who didn’t wish to be identified for the story, says she was keen to discuss the state of affairs in hospitals from the point of view of health workers, but desisted because she wasn’t “sure if I could depict the truth”. “I am now focused on helping by sourcing medicines and oxygen. Putting my head down and moving forward is my agenda.”

Women do have it worse. Last year, comedienne Agrima Joshua was attacked because she made a joke about Maratha ruler Chhatrapati Shivaji. She said the attack on social media “was so organised, it was like a swarm of locusts”. She was threatened with rape, and there were calls made that indicated harm to members of her family.

Rohan Joshi has been oscillating between sharing good humoured posts and necessary health information on Instagram. He left Twitter last year because of incessant trolling

Watching world news, and seeing how far their counterparts in the Western world can go, makes this doubly depressing. The former President of the United States, Donald Trump may have run America into the ground, but there wasn’t a news bulletin or late night variety show that didn’t poke fun, and in a biting way, at the Trump administration. They went all out, stopping just short of using expletives. In 1998, President Bill Clinton was the subject of more than 1,700 jokes on late night television, according to a report by Robert Lichter, professor of political communications and sociology at George Mason University. According to Lichter, in 2017, there were more than 3,100 jokes made about Trump during late night programmes. He noted that in 2020, Trump jokes outnumbered Joe Biden jokes 30-to-one.

Interestingly, some of them have found inspiration in India’s mismanagement of the crisis. They are critical of the Modi government for lack of planning in the Coronavirus pandemic. South African comedian Trevor Noah, who hosts The Daily Show on American primetime, in a segment on India on April 27, said, “The really sad part about this crisis is that it could have been avoided if India’s government hadn’t taken their eye off the ball.” He took a dig at the PM when he explained how he must have responded to the crisis with a strategy that said, “We’ve got to stop the spread...of these mean tweets about me”, before adding, “You know things are getting bad when a leader’s response to criticism of his failures is to try and shut down the criticism, not the failures.”

Back home, a few comics are trying to use their upper caste Hindu privilege to make a point. On May 5, in a teaser of the next episode of his YouTube show Ten on Ten, Vir Das posted a visual disclaimer: “If you are triggered by jokes about death and are currently grieving, I humbly ask you to leave the show right now…” India’s most popular comedy export internationally, Das has been cooped up in his London accommodation for months. But don’t think he is hiding. He is back in India as of last week. As the country saw the second COVID-19 wave spread like wildfire, the comedian who has been a steady critic of the current government, took jibes at the lack of governance through tweets and videos. In his next episode, which airs today, he tackles the “elephant in the room” as he puts it. “I have to do my job and I am not going to not do my job because the elephant is a dead body,” he says early on in the interview to mid-day. “It’s not about trying to think of what is off limits but addressing what is at the back of everybody’s mind. You don’t go into comedy in a month like this without discussing all the imperative subjects. Everyone is heartbroken and the nation is collectively in grief.”

Of course, no one makes fun of the dead. But can one even attempt an intelligent oxygen joke? “We’d only know that once the jokes have been cracked. But I am not here to skirt the subject. Things like oxygen and lack of good governance may or may not come up, but one has to talk about grief. That’s the emotional hinge for me. Everybody I know has lost someone they love and in trying to make them laugh, it’s essential to put the situation into perspective. I have tried to find things that others are afraid to say or have been unable to say. This isn’t entirely because of fear; it is as much because they are too broken and numb. I draw from my friends, from what I see around me and how I feel. I go into writing a set saying laughter is beautiful and I need to make people laugh. I don’t go in wanting to give them hope; they’ll have that after a good session of laughter anyway. It sets off the right chain reaction in the human body that fills you with optimism. In a moment like this what choice do we have but to be hopeful?”

Das’ approach to comedy isn’t about finding a balance. “The jokes that can make an entire room uncomfortable are the ones that fascinate me.”

Rohan Joshi, who shot to fame with the genre-changing All India Bakchod, which went kaput after several senior members were accused of sexual harassment in the 2019 #MeToo movement, has been keeping the comedy flag flying, with balanced posts that oscillate between subtle humour and necessary information. As he says, “One of the things ailing comedy is that issues that would be fine to laugh about earlier are not right now. The context has been soured, and simple things have lost colour. Forget comedians holding back, even environmentalists have to hold back information that [the common man] should have access to right now.”

He says that for him, comedy is usually “tragedy plus time”. “There are some horrible things happening right now. And a couple of years from now, we may laugh at what we landed ourselves in, and that will be darkly funny. Right now, it’s an active tragedy.” Joshi, who left Twitter in 2020 after what he calls a “circus of abuse”, and finding his personal number leaked online, agrees though that to stay quiet right now would be criminal, whether you are a comic or otherwise. “People have reached a snapping point, and are feeling spectacularly let down by those they voted to power.”

Juhu-based comic Atul Khatri, who left his family business to do humour full time at 43, says that this privilege as an upper-class Hindu has not been serving him all that well. He has been watching each step, and his sets are thought out. On Instagram, he does fun videos under a series titled, Only Good Newses. He has received threats in the past, and says that trolls tend to morph tweets and comments in such a way that they can exploit them to incite people. “I had one day tweeted about the PM being on TV, and said, Modiji on TV. This was changed to ‘bakc***ji on TV’.”

Khatri is keen to put his own mental health first. He may just go off social media entirely. Eventually. “[Right now] we can’t stop ourselves from speaking up. People are dying around us. You have to know where to draw the line. I did a corporate event where they asked me to make jokes about the virus, and I said no, it’s not funny. I now self-censor my jokes.” Though Khatri does say it could be a time for reckoning for the comedy circle, he also thinks, it could nudge the bright and brave to write smarter jokes. “You can make a point without naming someone. For that you need to work hard. The joke has to be something that makes it possible that saanp bhi mar jaaye aur lathi bhi na toote.”

3,100

No. of jokes made about then President Donald Trump in 2017 on late night American television, according to Robert Lichter, professor of political communications and sociology

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!