Research, environmentalists, and mental health experts all agree that the rising temperatures impact mental health

Arpita Mallick is concerned about how frequent load shedding is affecting her dog, Uno, who has a pre-existing respiratory problem. Pic/M Fahim

Heer Nimavat has been exhausted attending class at Miranda House in Delhi. Her college has held classes through summer, and the rise in temperature has affected her productivity for the past month. “Would they have classes in Canada if it was snowing?” asks the first year BA (English) student. “It doesn’t have to be a physical obstacle for it to be an obstacle.”

ADVERTISEMENT

With the Indian Meteorological Department (IMD) recording March 2022 as the hottest month in 122 years, heat-related frustrations have been rising with the mercury. According to the IMD, a heatwave in the plains is characterised by temperatures higher than 40 degrees Celsius; it’s 37 degrees in coastal areas and 30 degrees in the hills. If the temperature of a region goes 4.5 to 6.4 degrees Celsius higher than normal, it is termed a heatwave; If it is greater than 6.4 degrees Celsius, it’s declared a severe heatwave.

In March, the hottest month according to IMD in over 100 years saw the temperature rise to almost 40°C in Mumbai. Pic/Sayyed Sameer Abedi

In March, the hottest month according to IMD in over 100 years saw the temperature rise to almost 40°C in Mumbai. Pic/Sayyed Sameer Abedi

Nimavat observed that the hotter it gets, the more she and her friends crib. She lives on the top floor of a building, right below the terrace. “It [the room] heats up during the day, and the nights are terrible,” says the 19-year-old, who has a fan in her room, which is no match for Delhi’s harsh summers. The heat has affected her overall productivity, she said during a telephonic interview.

According to a 2021 research paper by the Imperial College London, climate change has a significant and multi-faceted impact on mental health and emotional wellbeing. Data shows that there is a clear relationship between the effects of climate change—such as rising temperatures, or more frequent and severe weather—and worsening mental health. In extreme cases, it could also spur suicides.

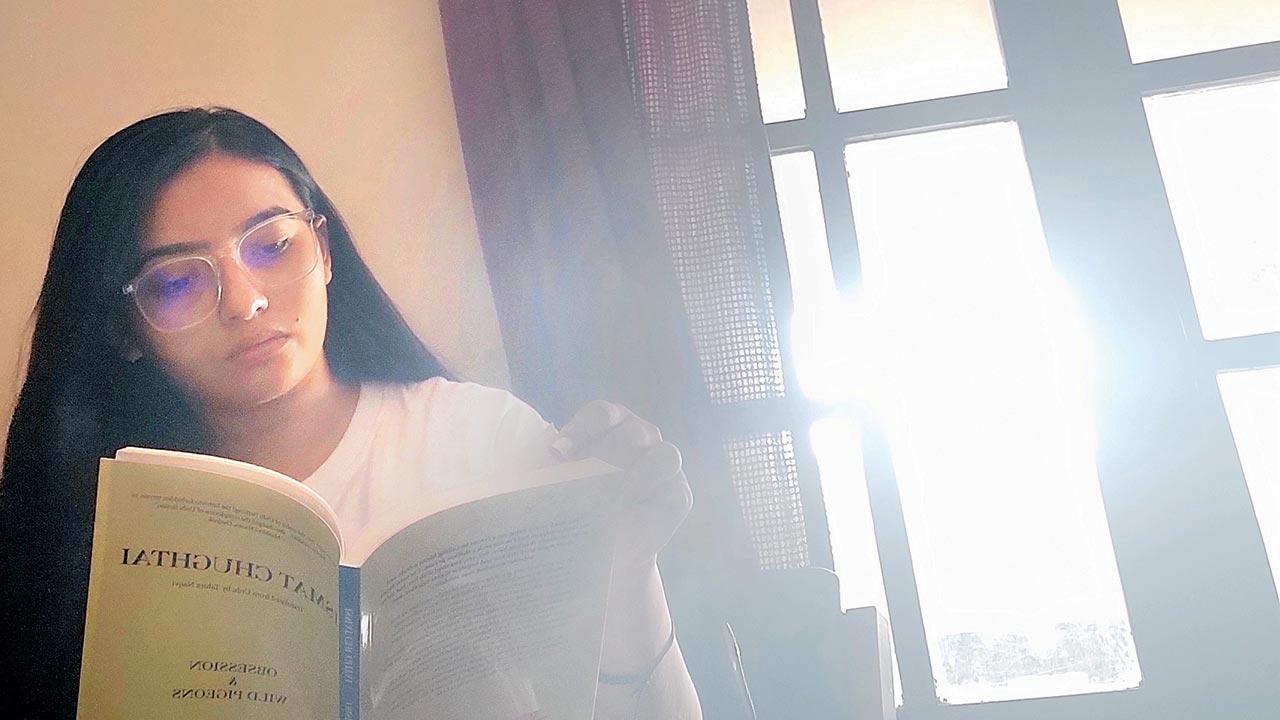

Delhi-based Heer Nimavat has only a fan in her hostel room. She gets frustrated by the heat and it often affects productivity

Delhi-based Heer Nimavat has only a fan in her hostel room. She gets frustrated by the heat and it often affects productivity

The research further states that heat waves and extremely high temperatures are associated with a range of negative societal outcomes and increased risks, which may, in turn, influence mental health. These include reduced economic output, increased conflict and societal violence, and disturbed sleep. It even affects blood flow and the central nervous system, which leads to cognitive and emotional changes that impact mental health and emotional wellbeing adversely. Unable to work, Nimavat and her peers head back home early. “I write poetry,” she says “and there seems to be displacement, sometimes mental and sometimes physical, in creativity. It is very difficult to be in the creative space when the physical surroundings are not comfortable,” she says. While she is aware that she comes from a place of privilege, the frustration and fights with her peers keep increasing with the temperature.

Anastasia Dedhia, chief psychologist at Mind Mantra, says that there has been tremendous research and proof that increase in heat is directly proportional to change in temperament. “We study this as students,” she says. “When you put an individual in a high temperature environment, his aggression will rise proportionately.”

Tanisha Goveas

Tanisha Goveas

Tanisha Goveas, a mental health expert at AtEase, an inclusive mental health platform, has had heightened emotional outbursts since April. Where earlier she could patiently wait for her cab driver, reasoning that (s)he might be stuck in traffic, she is now easily frustrated if her ride is delayed. “The frustration comes with misery, which gives way to sadness and bouts of crying,” says the Mumbai-based resident. “Many of my clients are also feeling lethargic, more stressed and upset, and I am no different from them,” she says. “Even the slightest change is a bother.”

This is a particular kind of discomfort caused by the excessive heat affecting bodily functions such as digestion. The kind of frustration felt by one person in an air-conditioned room is qualitatively different from the type experienced by someone on the street or stuck in traffic without an AC. Heat is an existing stressor and everything else just adds to it. “I live in Andheri,” says Goveas, “and can keep the AC on all day, overlooking the high electricity bill. But what can someone who lives in an area with frequent power cuts do?”

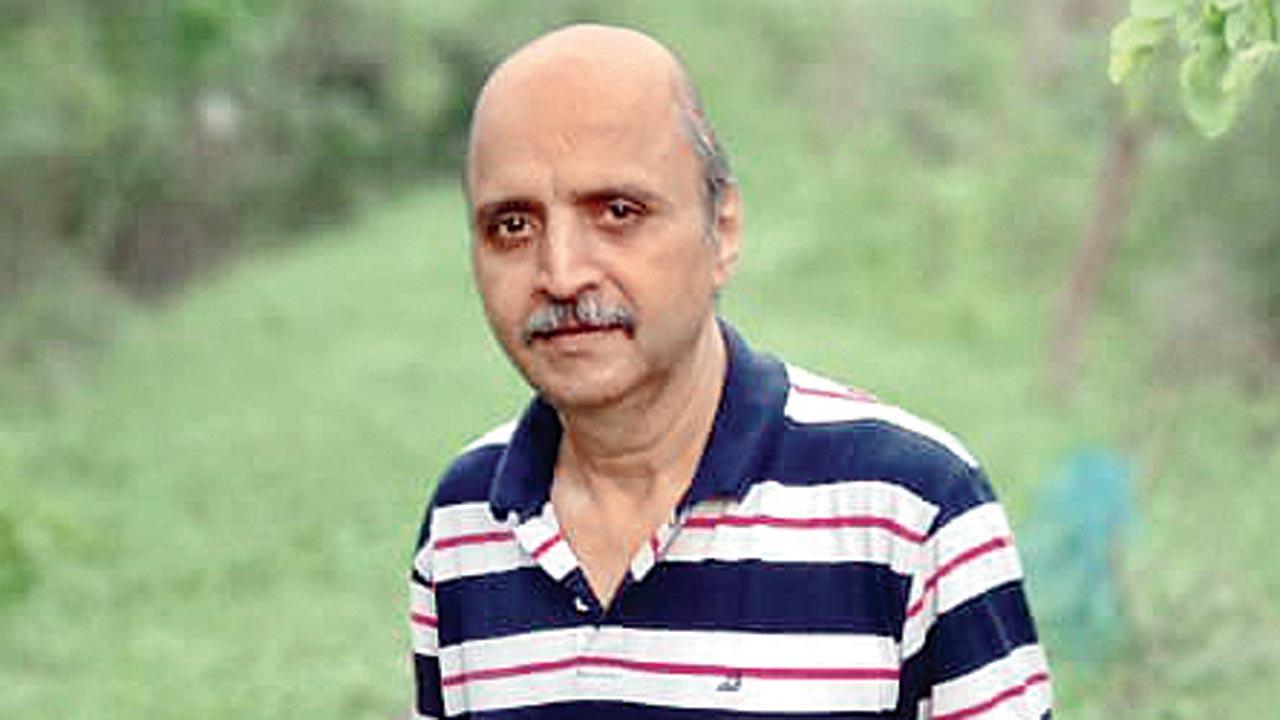

Salma Prabhu

Salma Prabhu

Environmentalist and director at Mumbai Sustainability Centre knows how privileged he is when he talks about how the heat wave affects those in the lower socio-economic bracket. In the case of Mumbai, humidity adds to the overall physical discomfort.

“The middle and affluent class can escape to an air-conditioned environment, but the poor cannot,” he says.

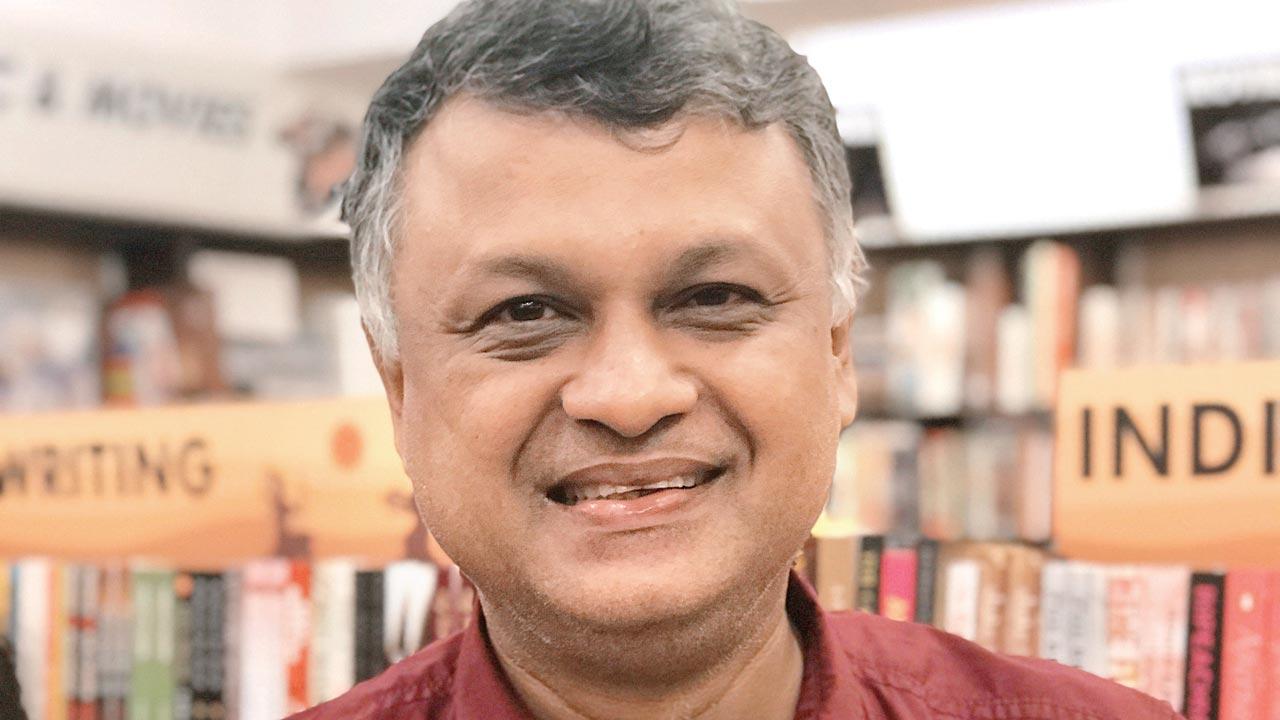

Harish Pandey

Harish Pandey

The Central Institute of Psychiatry (CIP), Ranchi records a steady increase in footfall every year from March to June. Dr Basudeb Das, Director of CIP, says this year the average number of patients needing diagnosis of mental health issues increased by 10 to 20 per cent. “The unprecedented heat wave is one reason for this,” says Das, “The second is the COVID-19 pandemic.” According to him, the heat can encourage bipolar disorder and manic excitement.

Heat rage can be similar to the seasonal mood disorder prevalent in Europe, where people feel depressed and sad in winters due to the lack of sunlight, and feel the opposite-euphoria—in summers. In India, explains Das, this phenomenon is sometimes reversed. “In winter, people may experience mania and depression in summer,” he says.

Dr Basudeb Das

Dr Basudeb Das

“A normal annoyance response would be blaming the government, world, and those who are harming the environment, etc,” explains clinical psychologist Salma Prabhu, who is also a career counsellor, author and environmentalist. “A person with moderate and severe mental health issues may suffer frequent bouts of anger and frustration. A small incident could set off a fit of rage or other extreme reactions.” She adds that women who are pre-menopausal or menopausal experience hot flushes, and this extreme weather can trigger strong anger outbursts.

Arpita Mallick, a big data engineer, recalled having a similar fit in front of her flatmate recently. They live near an industrial area in Pune due to which her residential complex experiences load shedding frequently. Being new to the city and work-related stress add to her frustration. To make matters worse, her dog, Uno, has a respiratory problem and starts panting if he’s too hot. Watching her dog suffer triggers Arpita and makes her feel helpless. Moreover, taking care of him alone, along with her daily chores and frequent power cuts adds to her stress. “When the weather is cool or it’s just about to rain,” says the 23-year-old, “I feel much better when I wake up. When it’s hot, my mood sours as soon as I wake up. I have to take Uno for a walk in the heat, and manage work and battle power cuts.” She also has to time her dog’s vet visits; he gets restless in the afternoon.

Anastasia Dedhia

Anastasia Dedhia

Aggarwal points out that in a stressful city such as Mumbai—which doesn’t have a good reputation in terms of standard of living—only 20 to 30 per cent of the population can afford air conditioners. “We don’t research this because we are not affected, but the lower socio-economic class is completely squeezed by the absence of access to air-conditioned spaces or to open spaces. They live and work in crammed spaces, ” Aggarwal says, adding that the rise in temperature also has a direct impact on mental health of those in the agriculture sector. “I work with marginalised farmers, and the impact on income is direct,” he says. “Climate-induced impact on agriculture is very real; it means unpredictability of crop output and thus, the income.”

Harish Pandey, member of the New Link Road Residents Forum in Dahisar, says that people are moving to cooler places which have better green cover. “We are consistently losing our green cover pan India,” says Pandey. “As far as Mumbai is concerned, we should not only talk about mangroves, but also the wetlands.” Land near the coast is wet because of the ingress of sea water. “Reclaiming the wetlands, converting them into dry lands and effects of climate change are felt faster,” says Pandey. “So it is paramount that these wetlands are saved. Mangroves and Aarey are natural air conditioners. The air in them is cooler, which gets displaced by breeze and dilutes the hot urban air. More than any other time in the city’s history, now is the time to take care of the environment. The city has to win the battle of environment vs. development so that large urban green areas such as the mangroves, Sanjay Gandhi National park, Aarey Colony and even larger public parks are saved, says Aggarwal. Pandey corroborates that the temperature around Dahisar mangroves is three to four degrees lower than what it is at Dahisar station.

Rishi Aggarwal

Rishi Aggarwal

“Aarey [Colony] has been an open refuge for people,” says Amrita Bhattacharjee, one of the activists fighting for the conservation of one of the lungs of the city. “When there are so many trees in one area, the temperature will go down. It is also a barrier against noise and pollution. As a forest, it absorbs more water, and hence the groundwater level there is very high.” She says auto-rickshaw drivers park their vehicles under a tree at Aarey Colony and take a nap. “As you enter Aarey forest, the temperature drops by 1.5 to 2 degrees,” she says.

A 2018 study conducted in Philadelphia by the Perelman School of Medicine, and the School of Arts and Sciences, found that the depression experienced by people living near a green cover was 41.5 per cent less than that experienced by those living in barren lands. The study also observed that those living near green lots also reported a nearly 63 per cent decrease in self-reported poor mental health as compared to those who didn’t. “Mumbai is losing tree cover every year as more infrastructure projects come up,” says Bhattacharjee, “It has become a heat island. Even proximity to the sea is not helping us. Earlier, the sea breeze would sweep the pollution away.”

Amrita Bhattacharjee

Amrita Bhattacharjee

Experts believe that the level of concretisation in the city is at an all time high, and that’s bringing down the water table level, increasing humidity. “Citizens need to speak up,” says Bhattacharjee, “The per person open space in the city is only 1.24 sqm, when it is required to be around 9 sqm as per WHO.” All of the experts we spoke to agree that citizens need to hold the government accountable, and also ensure that those filing a complaint should not be vulnerable. “Mumbai is a blessed city with its jungles, beaches, Sanjay Gandhi National Park, flamingo sanctuary and mangrove forests. We have many such natural resources; we just need to plan development around it rather than destroy these gifts,” concludes Bhattacharjee.

1.24

Sqmt of open space per person in Mumbai

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!