Indian kids who have set foot in school for the first time after online lessons right through the pandemic, are proving to be handful for teachers and parents alike

Yogesh Tambe says his daughter Abigail, 6, who has got used to attending online class under her mother Sugi’s supervision was “in shock” when she was told she had to attend physical school

Kushika Srivastava, 36, is worried that her daughter Sharanya, 6, might refuse to sit for exams scheduled later this month. The resident of Wellington, a town in the Nilgiris, says that Sharanya has attended a big chunk of her formative schooling years online. She struggles to write with a pencil, and at the pace that teachers expect her to. “Initially, she was excited to go to formal school for the very first time, but she complains and is struggling to cope.” Since lower and upper KG classes were more focused on activities and verbal lessons, she’s finding it hard to accept written work. “In Class I, which she joined directly when she returned to offline school, her subjects are no longer limited to English, Hindi and Math. She also has Environmental Studies (EVS) and Computers. She says her fingers hurt and refuses to get out of bed and hopes she can go back to virtual class,” shares Srivastava. The mother has little choice but to improve Kushika’s timing, making her write for 20 minutes straight while setting a timer. It’s all to prep her for the upcoming exams. In LKG and UKG, all she did was tick multiple choice question answers on a Google form. The half yearly exams, held late last year, were a mix of online (MCQ) and offline exams where question papers were sent in advance to the parents, and since children were writing them from the comfort of their home, there was no time limit. This will be the first test without her mother’s presence. “Children [of Class I] have no idea what exams are. If she leaves questions unanswered, I’m not sure what we can do.”

ADVERTISEMENT

Srivastava says the trouble doesn’t end once she’s off to school. When she returns, the last thing she wants to do is write some more and complete her homework.

“Sometimes, I give her a break, send her out to play or cycle.”

Sharanya Srivastava, 6, a resident of Wellington, who has been exclusively used to verbal lessons for the last few years, detests writing. Her mother worries that she may refuse to sit for the upcoming school exam, her first, altogether

Sharanya Srivastava, 6, a resident of Wellington, who has been exclusively used to verbal lessons for the last few years, detests writing. Her mother worries that she may refuse to sit for the upcoming school exam, her first, altogether

It’s a struggle that parents across the country are experiencing. In Virar, Yogesh Tambe, 47, received a message last week about the mandatory attendance of children at school. His daughter Abigail, 6, “is in shock”. Tambe says it also has to do with how she was informed of the change by the teachers. “‘You all have had a lot of fun, now you will learn the answers by rote and write them’, they were told. The exams are within a month and they are asking students to memorise everything. At home, we were around to help her with a difficulty and cross a hurdle.”

Psychologists say that Class I students are experiencing what kids usually do in Lower KG.

Andheri resident Nikita Bhavsar, 39, who runs a marketing agency, says she noticed that once her daughter four-and a-half year-old Kyra Shah returned to physical school, she showed signs of separation anxiety. Pic/Sameer Markande

Andheri resident Nikita Bhavsar, 39, who runs a marketing agency, says she noticed that once her daughter four-and a-half year-old Kyra Shah returned to physical school, she showed signs of separation anxiety. Pic/Sameer Markande

“The purpose of first year at school is about learning and memorising, but also growing accustomed to separating from home and parents and realising that it’s safe and fun to do so,” explains Delhi-based Nupur Dhingra Paiva, child psychotherapist and author of Love And Rage: The Inner Worlds of Children. Jehanzeb Baldiwala, therapist and co-founder of Narrative Practices India, agrees. She argues that using fear is counter-productive. Teachers would do well to convince children about the fun times they can look forward to instead of using threats and ultimatums. “In fact, schools should ponder whether Class I kids need to have a written exam at all. Grading can be done through oral exams with some minimal writing. I think a period of six months is necessary for the children to transition towards written exams.” Baldiwala works with children experiencing anxiety, depression and school-related problems.

While it is the workload that is affecting some, for others, it is what experts are identifying as separation anxiety. Andheri resident Nikita Bhavsar, 39, noticed that her four-and-a-half-year-old daughter Kyra would display nervous tension when she’d pick her up from school. When she had to head out of town for a professional assignment, and returned, she found Kyra listless. The kid who’d be up at 7 to head out was a picture of weakness. “When I asked her what the matter was, she said, ‘mom, I don’t want to leave you’.” Bhavsar says Kyra is lucky that her school introduced limited class hours before moving to full-time school: 1.5 hour classes twice a week for two weeks to a week of 1.5 hour classes on all five days before switching to three hour-long classes all week.

The management and teachers at Campion School, a sought-after South Mumbai school for boys, say that the focus for now for Class I and II kids is to get them acclimatised to the environment, the teachers and each other. They are using recitation to improve listening skills, and show-and-tell to help the shy ones open up

The management and teachers at Campion School, a sought-after South Mumbai school for boys, say that the focus for now for Class I and II kids is to get them acclimatised to the environment, the teachers and each other. They are using recitation to improve listening skills, and show-and-tell to help the shy ones open up

Juhu-based Swapnila D’Souza’s son Ethan, 6, was crying inconsolably a day before he was to join physical class. “He was playing with his friends in our residential society. When somebody told him the schools were restarting, he was scared. Although he had not ever attended formal school until now, he believed it would be terrible. We managed to convince him and get him ready in time for the school bus. When he returned home, I asked him what he had liked best, and he said, ‘the bus ride’,” D’Souza, 38, remembers. It has been over a week, and the kid is yet to warm up to school. He is expected to take down notes from the black board at a pace he can’t match. Because he struggles to focus, his teachers sometimes resort to making him stand and write. “He is cranky and complaining of his hands and legs hurting. I try to make him forget those moments by turning his attention to goodies made for lunch.”

To make the transition easier for first timers, Baldiwala suggests that schools allow young children to bring an object, perhaps a favourite toy, so that they carry with them a sense of belonging. Additionally, schools can assign each child a buddy so that the companionship comes with consistency. “Concentration has definitely taken a hit. Young children are paying attention when the teacher talks directly to them or makes them do an activity but the moment she turns her attention to the whole class, she has lost the individual kid,” says Baldiwala, suggesting that teachers may want to follow the same routine they did during online school. “If there was a rhyme or song which they would begin the virtual class with, they should continue,” she adds. When it comes to parents, Paiva suggests that they spend more time talking to their children and hearing their concerns. “Schools are not equipped to always handle the emotional concerns of children. Parents have to work at calming the child, focus on the exciting things in class”.

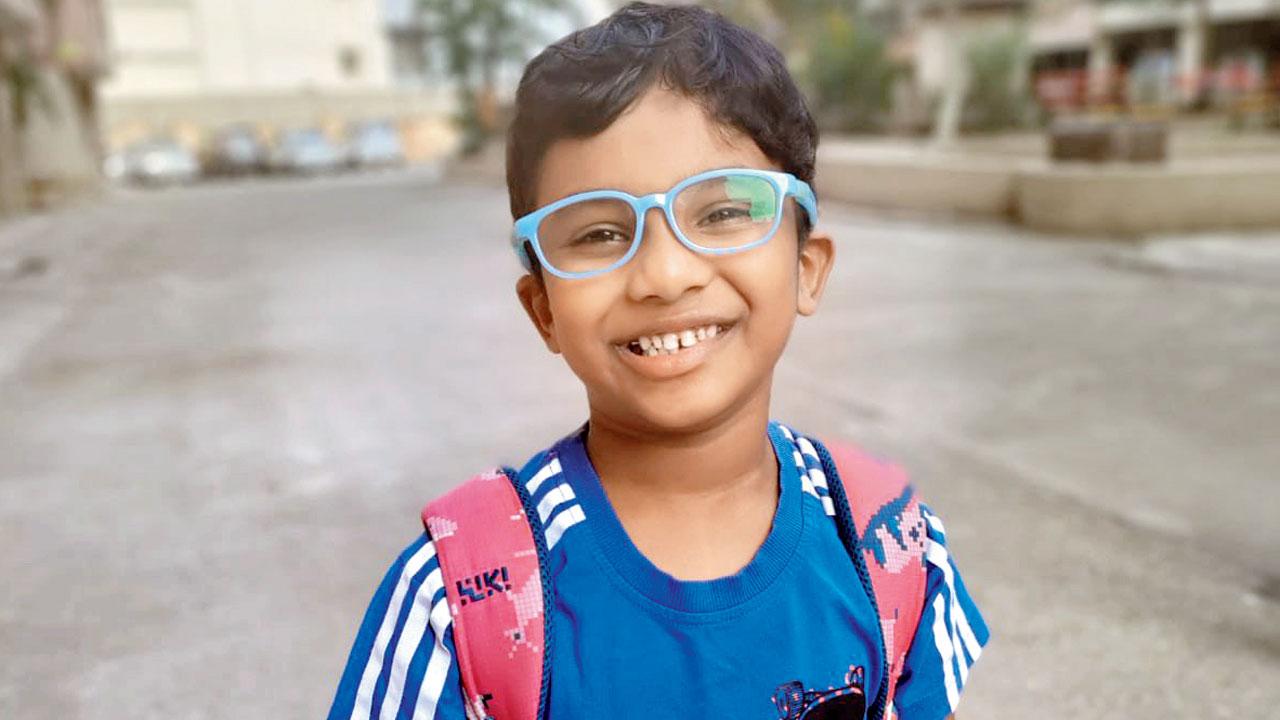

Ethan D’Souza, 6, finds nothing exciting about school except the bus ride, he told his mother Swapnila

Ethan D’Souza, 6, finds nothing exciting about school except the bus ride, he told his mother Swapnila

At Campion School, a private Catholic primary and secondary school for boys located in Colaba, teachers are ideating on how to make the transition smooth. “We decided not to focus on academics for the first 10 days. Instead, we try to make the environment tempting for our boys to return. We decorated our school and gave the students small presents to take back home,” says Principal, Fr (Dr) Francis Swamy SJ.

Dorothy Dias is the Junior School Coordinator at Campion, and speaks of the activities and games they organised to break the ice among children of Class I and II who had never met their classmates in person. “Children are feeling shy when it comes to speaking in front of the whole class, so we started show-and-tell activities. To build listening skills, we are involving them in recitations. To build their motor skills, we are taking them to outdoor spaces to play football and do PT exercises. We have also realised that writing is a challenge for them, so we will work on building their pace. But for now, the focus is on getting them adjusted to the system, teachers and each other.”

Nupur Dhingra Paiva and Jehanzeb Baldiwala

Nupur Dhingra Paiva and Jehanzeb Baldiwala

UNICEF’s guideline for parents

. Remind children about the positives of going to school—they will be able to see their friends and teachers

. Listen to their concerns and respond in a calm, supportive and reassuring way

. In the week before joining class, bring back the usual wake up, bed and breakfast routines. Encourage them to check their school timetable and get their school bag ready

. Drop your child to school to build a greater sense of security

. Once they return from school, talk to them about their day, what they are looking forward to the next day, and what they enjoyed the most in class

One of the longest closures in India

UNICEF released data at the start of 2021 that revealed that schools for more than 168 million children globally have been completely closed for almost an entire year due to COVID-19 lockdowns. One in seven children have missed more than three-quarters of their in-person learning. The analysis of school closure report noted that 14 countries worldwide had remained largely closed since March 2020 to February 2021.

In India, closure of 1.5 million schools due to the pandemic and lockdowns in 2020 has impacted 247 million children enrolled in elementary and secondary schools. “We must strive to support them in catching up on the learning they have missed. Further, the mental health and well-being of children is a crucial concern. Psycho-social support from teachers, parents and caregivers is a priority,” said Dr Yasmin Ali Haque, UNICEF India Representative.

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!