A new book explores the reasons for the Mahatmas hallowed presence on canvas for over a century, despite his slippery and inconsistent views on art

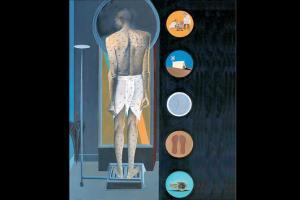

Surendran Nair, The Unbearable Lightness of Being, Corollary Mythologies, 1998. Oil on canvas. mage courtesy /Surendran Nair, Sakshi Gallery

Do I really look like that?" Noted artist Mukul Dey (1895-1989) remembered Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi asking him, when Dey showed him a pencil portrait that he had sketched. Dey had been granted an introduction to the Mahatma by Sarojini Naidu in Madras, now Chennai, in 1919, at the home where he was then staying. And while Gandhi had been informed of the errand that had brought Dey there—which was to "create with broad strokes the look of a new kind of leader"—he didn't pose like an artist's subject otherwise would. Instead, Dey recalled, "Gandhiji smiled sweetly at me, as if signifying his consent to my doing his portrait. He went on talking to the people in the room." The portrait, a side profile of Gandhi in close-cropped hair, a dark moustache and a prominent shikha, was completed in an hour. Although, it's hard to say from Dey's own retelling of this incident, whether Gandhi had been impressed with what he saw, the portrait came to represent the beginning of an insatiable fascination for the Mahatma among artists within the country and outside.

ADVERTISEMENT

Academician and researcher Sumathi Ramaswamy's new book, Gandhi In The Gallery (Roli Books), explores why the Mahatma's hallowed presence on canvas and paper for over a century, and in different mediums, is not a mere coincidence. It has stemmed from a pre-occupation with Gandhi's acts of disobedience and defiance, be it the way he lived, dressed or the manner in which he pursued the fight for freedom. "Gandhi was a master choreographer of his own image," shares Ramaswamy, who is James B Duke professor of History and International Comparative Studies, and Chair of the Department of History, Duke University, Durham, North Carolina, USA.

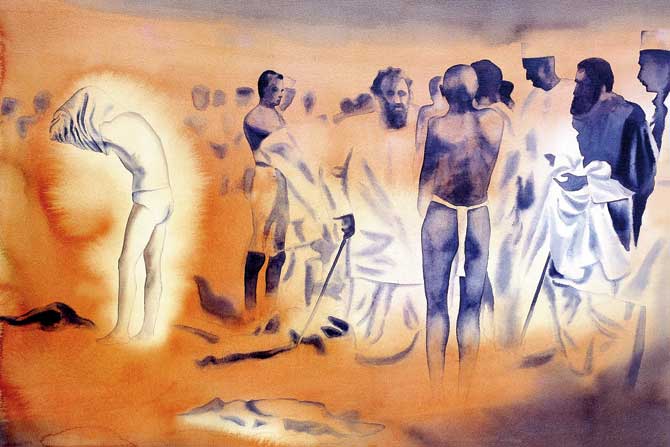

Atul Dodiya, Sea-Bath (Before breaking the Salt Law), 1998. Watercolour on paper. IMAGE COURTESY/Atul Dodiya

Her interest in Gandhi as the artist's muse goes back over a decade, when she wrote her monograph, The Goddess and the Nation (2010), in which she explored the colourful lithographs that feature him as Mother India's devoted son—a paradox, she says, given that he is also "the father of the nation". "While I was working on the project, Delhi-based curator Gayatri Sinha approached me and that led me to write an article titled, The Mahatma as Muse: An Image Essay on Gandhi in Popular Indian Visual Imagination. That appeared in her edited volume for Marg publications in 2009 titled Art and Visual Culture in India, 1857-1947. In this essay, I explored the paradox of Gandhi serving as the muse for so many artists who produced for the mass-market and yet was himself very ambivalent about art qua art, and especially about bazaar lithographs [he wrote pungently against these 'caricatures']," she says in an email interview. In both these projects, Ramaswamy was firmly focused on popular, mass-produced art, rather than singular high-end gallery works, which is now the dominant focus of her new book. Gandhi In The Gallery allowed her to refine as well as critique her earlier arguments. She realised over the two year-long research that satyagraha in itself was an aesthetic form, and that the art that stemmed from reimagining 20th century's great prophets of disobedience, was in effect, the "art of disobedience."

Gandhi wasn't an easy subject. When Switzerland-born Frieda Das née Frieda Hauswirth travelled to Cuttack in December 1927 with the desire to "sketch Gandhiji," she was told that the Mahatma did not pose for artists, and had "neither time nor desire for the arts". Ramaswamy, who is also currently working on a project on 'Gandhi and the camera', says his unwillingness, probably stemmed from his own prejudices about art and the artists. "Quite early on he developed a deep suspicion of the camera and its work—exploring this aspect led me to also conclude that he was really deeply suspicious of the image—and really anxious about 'idolatry,' namely, the worship of images. There might have been religious roots to this suspicion, but I also think it goes back to his views on art," which she says were often "slippery and inconsistent".

Sumathi Ramaswamy

"He really worried about art as a "mediator," as something that comes in the way of a direct apprehension of nature. It is in that sense he also referred to Nature—or God—as the true artist." The best source on his view, however, was the dialogue Gandhi conducted on this question in October 21-22, 1924 with the Santiniketan-trained Gandhian G Ramachandran, subsequently printed in Young India. "It is here he stated point blank that 'all true art is… the expression of the soul', and dismissed most works of arts that he saw around him as not embodying 'the soul's upward urge and unrest.' Art, if it had to count for Gandhi, had to be 'useful'—and to be of service 'to the people'; hence, his emphasis on 'craft' rather than 'art' per se. So, he also had a rather utilitarian and even instrumentalist idea of what constituted 'art'," says the author.

Despite being a reluctant muse, he never escaped the artists' gaze. "One of the things that got me really intrigued in the course of this project is the fact that drawing, painting, sculpting Gandhi is almost a rite of passage with artists of India—and not just in Gandhi's lifetime but especially since the 1990s. Both the most famous of artists, and then newest have produced at least one work on him," she adds.

There are numerous reasons why artists were drawn to him; his "out of the box" thinking could have been the primary attraction, feels Ramaswamy. "I have suggested that minimally they see in him a fellow artist, someone who was seeking to live a life creatively and conducting his life in a creative manner. For artists since the 1990s, especially those on the secular Left, I have also suggested that they are drawn to Gandhi as a means to another end: he becomes a means through which to speak out against the growing intolerance of Indian society, the runaway consumption, the increasing use of state violence, and so on."

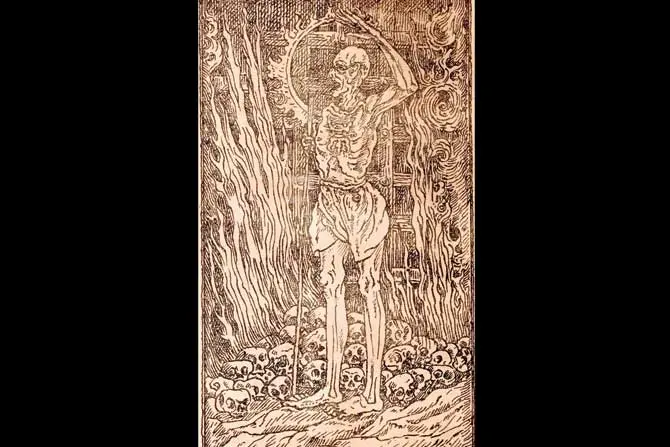

Gigi Scaria, Touch my Wound, 2007-08. Digital print. IMAGE COURTESY/Gigi Scaria

Gandhi, too, wasn't indifferent to some of the reproductions of him. While researching, Ramaswamy found several works of art that he "quite happily" had signed off on and to which he also added his signature.

The author points out how Gandhi's experiment with shedding clothes proved to be "enormously productive for image-making," with artists lavishing their attention on sketching his contours. "I have been careful in suggesting that Gandhi never went totally naked—that there was this tantalising oscillation between showing bare flesh and covering himself up with undyed khadi that may have been a source of his charisma—but yes, he was the only public figure of his time who showed so much of his flesh and in a consistent manner. Again, there is a kind of creative choreography of his body that I think catches the eye of the artist," she says.

In the book, Ramaswamy also takes great pains to analyse the art that emerged from Gandhi's pedestrian politics, the 1930 Salt March to Dandi in particular, and his camera-free death. Several photographers, including Homai Vyarawalla and Henri Cartier-Bresson, had narrowly missed being at the spot at Birla House on January 30, 1948, where Nathuram Godse fired at him. The lack of documentation made his assassination a product of fertile imagination for artists. "For me this was one of the most interesting angles to explore—that without the camera 'documenting' the moment and offering a 'corrective' [after all, let us not forget a crime was committed]—how the artist can give free reign to his or her imagination to visualise that murderous moment," says Ramaswamy. She was, however, most fascinated with the story behind the Felix Topolski paintings. "One of this artist's paintings in 1946 appears to visually anticipate Gandhi's killing by a gun. This is an enigmatic painting that I would have learned to do more with—I even interviewed his daughter in London, hoping to find answers in his private papers, but alas did not get far."

An artist who was completely invested in Gandhi was Maqbool Fida Husain. Gandhi, says Ramaswamy, was apparently his "favourite" subject "and his approach to the Mahatma borders on patriotic reverence. There is a kind of standardisation of look in Husain's Gandhi works—which are quite numerous, varied, and very evocative." But, what captivates this writer's attention is the works of two artists, who lived at different points in time, and have experienced Gandhi in different ways. Nandalal Bose (1882-1966), was probably the only artist, with the exception of Dhiren Gandhi, who was favoured by Gandhi. He was also summoned by the leader to set up an exhibition of paintings at the Lucknow session of the Congress party. In contrast is contemporary artist Atul Dodiya, born 11 years after Gandhi's death. Like Gandhi, Dodiya is a fellow Gujarati and a Kathiawari.

Nandalal Bose, Untitled, 1946. Pen and ink, reproduced as frontispiece. IMAGE COURTESY/Rakesh Sahni, Gallery Rasa

"There are so many things I find fascinating about Dodiya, not least his attempt to reach into the vast photographic archive of Gandhi and retrieve moments from his life that are not much discussed or known in standard histories of the Mahatma… he makes it speak to new truths that are relevant to our times." She points out to his diptych titled Paramhansa Yoganand Reading a Note, August 1935, where he "cleverly retrieves from the archives a photograph documenting an important encounter in 1935 at Gandhi's Sevagram Ashram near Wardha between the Mahatma and the US-based, but India-born founder of the Self-Realization Fellowship, Mukunda Lal Ghosh aka Paramahansa Yogananda". "In his widely-read memoir, Yogananda writes in great detail about a meal with the Mahatma, but does not mention the child present on the occasion. Dodiya's clever diptych pairing the photograph with Henri Rousseau's Child with a Doll (1892) cues us to the child's presence by Gandhi's side, indeed occupying the space between the two men. The child in the photograph [and in Dodiya's painting] is young Kanam Gandhi who, as his grandfather wrote in a letter from around this time to his grandmother, 'always has his meals with me.' By his painterly act, Dodiya alerts us to the ubiquitous presence of children in and around the Mahatma on a daily basis." With Dodiya, she feels she has barely scratched the surface. Probably, another book just on his formidable works of the Mahatma, she says will help her unravel more of his genius.

Keep scrolling to read more news

Catch up on all the latest Mumbai news, crime news, current affairs, and a complete guide from food to things to do and events across Mumbai. Also download the new mid-day Android and iOS apps to get latest updates.

Mid-Day is now on Telegram. Click here to join our channel (@middayinfomedialtd) and stay updated with the latest news

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!