A Bengaluru-based chef turns to the Malayalee women in her maternal family for a new book that talks about cooking, feeding, and other stories from their kitchens

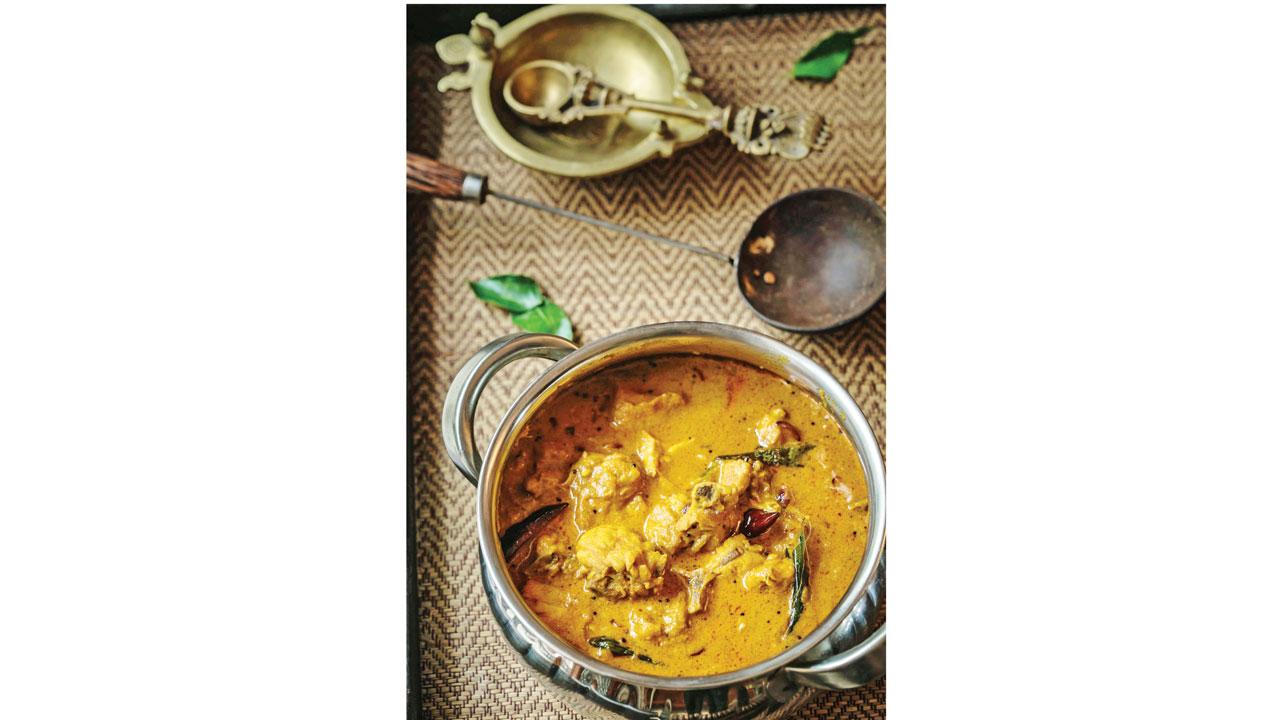

At Ammu George’s home, the red fish curry was made in a chatti (clay pot), sealed with banana leaves and softened over an open flame. Pic/Aysha Tanya

In Mamalassery, a quaint southern village in Kerala, a home on the banks of the Muvattupuzha river, capped by red tiles with walls painted in white and tangerine, has for nearly a century preserved an adukkala, a kitchen, where food is not just cooked, it is nurtured. “Within this home, the first matriarch presided over her family of ten... her helpers, all women, made halwa, dried mango thera and chakka kumbilappam wrapped in the leaf of a jackfruit tree, from scratch, endeavours that would take hours...” writes chef Tia Anasuya, in her just-released book, Adukkala: A Family Odyssey (R2,300), which draws upon memories and recipes from the kitchens of a generation of women who trace their roots to this house.

ADVERTISEMENT

Anasuya’s curiosity to stitch their stories together stemmed from a personal space—the Kerala home was a gift of her maternal lineage. Her grandmother, Ammu George, grew up in Mamalassery, where on the riverbank, they grew vegetables, like brinjal, chillies, long beans, pumpkins, okra, harvested coffee, and farmed their own fish in kolams (ponds). As a child, Bengaluru-based Anasuya remembers spending many summers in the ancestral home, but her connection with the adukkala would only grow on her during the pandemic. Having honed her culinary practice at Le Cordon Bleu in Paris, where she trained in traditional French cuisine, before stints at the famed Gaggan in Thailand, and other restaurant ventures in Dubai and Bengaluru, Anasuya found herself with her grandparents, early into COVID-19.

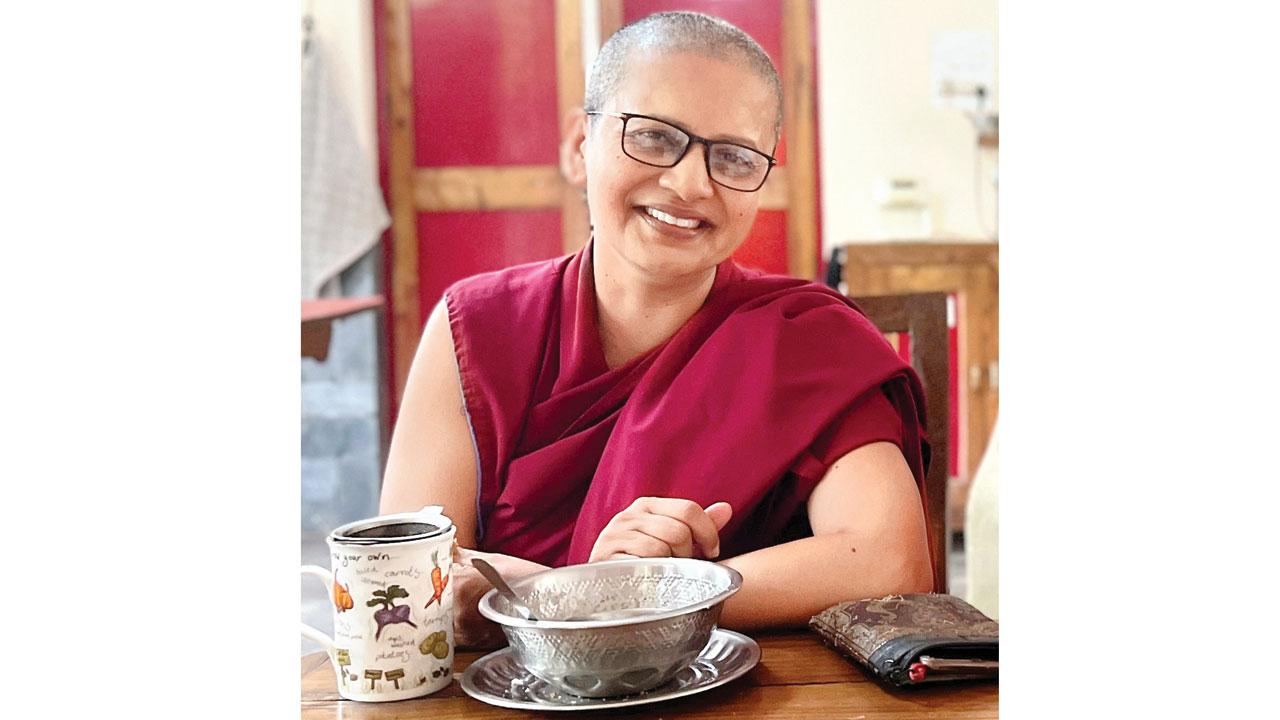

Buddhist monk Julie Thomas aka Tenzin Paldron’s first memory of food was the kanji and payar with chammanthi podi

Buddhist monk Julie Thomas aka Tenzin Paldron’s first memory of food was the kanji and payar with chammanthi podi

“Sometime before the lockdown was announced, in March 2020, my grandmother had this really bad fall. She was in Coimbatore, so my mum [Sheba Thayil] and I took the next flight to go and take care of her. We packed our bags for a week, but due to the lockdown got stuck there for three months,” says Anasuya, over a telephonic call. With her grandmother still recuperating, Anasuya took the reins of the kitchen. “The lockdown in Tamil Nadu was very strict, so initially it was difficult to get basic dal and rice. I had to rack my brains to figure out how to cook with minimal ingredients.”

Since her grandmother was craving comfort food, Anasuya found herself preparing Kerala dishes more and more for the first time, and under the supervision of the matriarch Ammu George. “I realised that I learnt much more in those three months than I had as a professional chef because there are these little tips and tricks that only a homemaker who has spent that kind of time in the kitchen, will be able to tell you,” shares Anasuya, who is the co-founder of a gourmet cookie business, Askew. “I just fell in love with Kerala food.”

The idea of documenting the women from her family took root around this time. The impetus was the stories relayed by Ammu George. “I would sit and talk to my grandmother through the day, and she would tell me about her idyllic childhood, growing up on a river bank, where they would eat their own produce,” she says, “It sounded like a fairy-tale. I never knew childhood like that.” Since food is Anasuya’s “love language” she decided to revisit these stories through Kerala cuisine. “The women who come out of Kerala are fierce. I wanted to throw the spotlight on them, and their relationship with food.”

For the book, Anasuya reconnected with 15 women from the family, with a few bonus chapters, which include those who had a deep influence on her cooking. “I picked the women who had the most to say,” shares Anasuya. “I knew most of them all my life. But until before I interviewed them, they were just Geeta or Deepa aunty to me. But by the end of it, I had come to know them at such a deeper level. They were just wonderful, resilient women, with stories that were as interesting, as they were varied.” Anasuya wasn’t necessarily looking at documenting the dishes they cooked, as much as the memories associated with them. “I am very interested in what makes people who they are, and for me, food ties into that in a huge and significant way,” she says, “The questions I asked them were about who they were as women, and what got them to start cooking in the first place.”

Tia Anasuya with her grandmother Ammu George. Pic/Aysha Tanya

The hardbound volume opens with Ammu George, who is married to veteran journalist and Padmabhushan awardee TJS George, and is mother to award-winning author-poet Jeet Thayil and Sheba Thayil, who also edited the book for Anasuya. Ammu, 88, recounts the preparation of red fish curry, made in a chatti (clay pot), sealed with banana leaves and softened over an open flame. Ammu’s mother was a fantastic cook, who taught the Achapenna (house cook) everything she knew. “My first memory of food from those days is fighting for Achapenna’s fish fry [vaala/ribbon fish] caught from the river,” Ammu shares in the book.

Then, there’s the story of Julie Thomas aka Tenzin Paldron, who went on to become a Buddhist monk. “She travelled the world, and during her travels, she would make the humble kanji and payar [red rice porridge and green gram toran],” says Anasuya. Kanji and payar fried with chammanthi podi (coconut and spices) and pappadam “is the first time I remember noticing food”, Thomas says in her interview with Anasuya, while speaking of the summers with her ammachi (grandmother) in Edaya, who would make her a delicious bowl. “It became my comfort, wrapped up in memories of my grandmother... one recipe, in particular, was not to be played with—chammanthi podi. The proportions had to be exactly right, and it had to be ground on the ammikallu [grinding stone], no excuses,” Thomas adds in the book.

Anasuya’s conversation with the monk in her family, reminded her how “food travels in time and space, and really stays with you”. Another relative, Ann Kailath, grew up in California but continued to have a deep appreciation for authentic Kerala food. When she moved to Boston, after marrying her husband Reji (a Syrian Orthodox), she started picking up Kerala dishes like chicken curry, sambar, kachimoru. Her mother-in-law’s meen molee (mildly-spiced coconut milk fish curry)—the best she has ever tasted—continues to be a favourite at home.

For Anasuya, her most treasured stories in the book came from her grandmum. “She is the woman who started it all... I think her memories of her childhood, running through the orchard of her home, climbing the trees and picking up cashew nut fruit, is what started the fire in me in the first place. She also told me how she wrote in the sand and learned the letters in Malayalam that way,” she says, adding, “It was such a beautiful and calming image.”

Samsara’s well-oiled Malabar chicken curry

Ingredients

500 gm chicken curry cut (skinned, medium-sized)

4 tbsps coconut oil

2 nos red onions (sliced thin, medium-sized)

4 nos green chilli

1 sprig of curry leaves

1 tbsp red chilli powder

1 1/2 tbsps coriander powder

200 ml coconut milk

Whole garam masala spices (1/2 cinnamon sticks, 4 cloves, 8 black peppercorns, coarsely ground)

1 1/2 tbsps ginger-garlic paste

1/2 tsp turmeric powder

Salt to taste

5 nos shallots

2 nos dry byadgi chilli

1 tsp mustard seeds

Method

Wash the chicken and marinate with salt and 1/2 tsp turmeric powder. Heat a heavy-bottomed, deep pan on medium flame with 3 tbsp coconut oil, add the whole garam masala spices and sauté for 2 minutes Add sliced onion, sauté till translucent, and add the ginger-garlic paste and stir to combine. Add green chillies, coriander powder and turn the heat low. Sauté till the raw smell of the powder is gone, add chicken and mix well. Cover with a lid and cook 5-7 minutes, then add curry leaves. Add the second extract coconut milk, cover and cook for 30-40 minutes on low flame. Add the first extract, simmer for an additional five minutes, then turn off the flame.

Tempering

Heat 1 tbsp coconut oil in a tadka pan, add the mustard seeds and allow to splutter. Add shallots and allow to brown, followed by byadgi chillies broken into halves by hand, and turn off the flame. Pour into the chicken curry and cover for a minute before serving.

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!