After SC lauds BMC for Covid-19 preparedness, docs and administrators weigh in on Mumbai’s inherent decentralised functioning, unlike Delhi, that’s working in its favour.

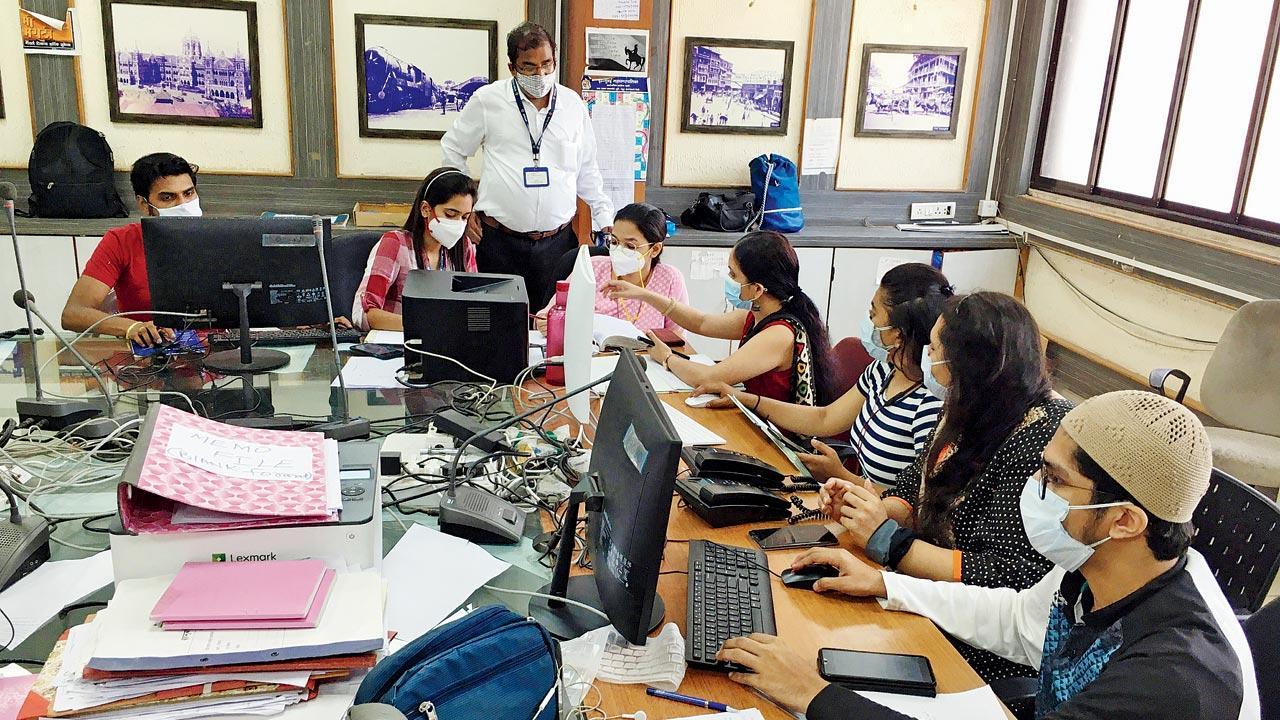

The team at BMC’s B Ward war room, which is one of the 24 Covid-19 war rooms set up around the city. Pics/Atul Kamble

In mid-September 2020, when the Covid-19 case count of Mumbai had climbed to over 2,05,100, with a 104 per cent increase in the number of cases when compared with the previous month, it appeared to be a dire situation. All cultural events for the year were cancelled and restrictions on movement were enforced. At the time, the O-word was still not such a cause for concern. “But, one or two cases at the time had given us a hint that oxygen could become a critical issue in the near future. Global trends were showing a similar trajectory. We had to act, and act fast,” says Additional Municipal Commissioner (Health) Suresh Kakani. Even in the lean period, from November to February, the prepping continued in full throttle.

ADVERTISEMENT

If the city is able to breathe easy today, with municipal commissioner Iqbal Singh Chahal publicly stating that all issues related to oxygen supply under the BMC stand resolved, it’s not without reason. Kakani says a multi-pronged strategy helped them turn the tide in time. “We had decided to keep most of our jumbo facilities, without downscaling. Yes, it meant spending huge money on operations and maintenance. Had we dismantled them [during the lull], resurrecting them would have cost us a lot more.”

Dr Pradip Awate, state surveillance officer for Maharashtra, says Mumbai’s administrative structure is conducive for decentralisation, which may not be as easy to replicate in Delhi; (right) Dr Sharang Madaan, a resident ICU doctor at Park Group of Hospitals, says the national capital is in dire need of skilled medical workers

He says the most crucial factor for them was time. Unlike private hospitals, public hospitals have to adhere to a set procedure at every step, whether it is procurement of supplies or tying up with manufacturers. “We started the procurement process for oxygen in September, which is why we were able to meet the oxygen demand.”

Also Read: Bengaluru adopts Mumbai model to tackle second wave of Covid-19

Recently, the Supreme Court praised the city’s response to the spread of Covid-19, proposing that it be replicated in Delhi. The bench headed by Justice DY Chandrachud took note of the submissions of Solicitor General Tushar Mehta that Mumbai managed with 275 MT (metric tonnes) of oxygen even when the active cases crossed 92,000. Taking a cue from this, Karnataka also issued directives to set up Ward Decentralised Triage and Emergency Response (DETER) Committees for Covid-19 management in all 198 wards in Bengaluru. The ward-level committees will have officials of the Bruhat Bengaluru Mahanagara Palike (BBMP), ward committee members, government officers, volunteer RWAs and civil society organisations. The directive states war rooms will now be set up in all 198 wards of the BBMP and they will be entrusted with activities related to COVID-19 management. The WDCs will be headed by a ward nodal officer. The focus of these ward-level committees will be to help people access hospital beds. The main objective of setting up the WDCs is that it will become the first point of contact with the government for Covid-19 patients in Bengaluru, it states.

Suresh Kakani

Switching from a cylinder-based system of oxygen to a central supply system, wherein huge oxygen tanks were installed in every hospital—makeshift and permanent—was one of their best strategies, feels Kakani. “When it comes to cylinders, almost 30 per cent [of oxygen] goes waste while changing the system. Let’s say a patient is critical, we can’t wait to empty the cylinder; we have to leave some [oxygen] in the system to maintain the pressure.”

The manpower requirement for changing the cylinder and ferrying it to and from isolation wards and ICUs, and then sending it for refilling, and bringing it back to the facility was humongous, too. “It involved massive human intervention at every stage. Even if one link is missing, the entire system can collapse. The centrally located system was equipped with pipeline supply, flow metre, regulator, and pressure metre, all of which came to our rescue during the crisis period.”

The oxygen generation plant at Delhi’s Deen Dayal Upadhaya Hospital that Mission Oxygen co-funded

Kakani says they did not solely depend on the information they were getting from hospitals about the demand for oxygen. “It wasn’t a case of demand and supply, but requirement and supply. I may ask for one metric tonne per day, but the question remains—what is my real requirement? And whether it is scientifically supported or not, is what we tried to verify.” They investigated the number of Covid-19 beds a hospital had, taking into account both the oxygen supply bed system and the ICUs. “Using a standard formula to calculate how much oxygen is required during peak time, we came up with a figure for allocation.”

Kakani says the oxygen demand in Mumbai at the moment is anywhere between 235 and 270 MT per day. “Our sanctioned capacity is 230 per day. Somehow, we are able to manage and save 20 to 30 per cent oxygen.”

Preeti Sharma Menon, senior leader in Aam Admi Party and Dr Rajesh Parikh, author of The Vaccine Book and honorary neuropsychiatrist at the Jaslok Hospital and Research Centre

During the last week of April, when Mumbai had just about begun to get a grip on the situation, the battle for breath had worsened in the capital. Amid the second wave, nearly 90 per cent of the country’s oxygen supply—7,500 metric tonnes daily—was being diverted for medical use, Rajesh Bhushan, Union Health Secretary, said in a statement.

Aam Admi Party senior leader Preeti Sharma Menon admits “everybody should have done better” in light of the tragedy that unfolded, when hospitals in Delhi were struggling to accommodate breathless patients, or even keep alive those who were lucky enough to find a bed. “It’s not that oxygen did not run out in Mumbai. I was handling the AAP’s Covid-19 helpline in the city and every day, we were hearing of death and devastation. The first three weeks of April were distressing.”

Where Mumbai trumped, she thinks, is when the city announced the lockdown. “They were quick to do that, and within two weeks, you saw a dip in cases. Decentralisation of wards into war rooms was also an effective strategy. It’s a good model for every city to emulate. The city has to be broken into smaller units; it could be assembly or zone wise.”

According to Menon, the first three or four weeks of a renewed Covid-19 wave in any city are traumatic. “Maharashtra peaked before Delhi. But, look at Delhi today, the positivity rate has come down below 20 per cent and there are empty beds now.”

In what has now become a familiar slinging match between Centre and state, Menon chooses to criticise the former’s response to the situation, adding that the capital was crippled as “the central government was asleep”. “They [Centre] were so busy patting themselves on the back that they didn’t think about medicines, oxygen or increasing infrastructure facilities on ground. In March and April, when hundreds of people were dying, India exported R6.5 crore worth vaccines. No other country did that. France exported only now, and that too only 10k, after majority of the population received its first dose.” She says Delhi came into the public glare because it’s the national capital. “People have died in Punjab, Karnataka, Uttarakhand, and we don’t even know the real figures in Uttar Pradesh anymore.”

With Delhi showing a decline in new cases of Covid-19, Delhi Deputy Chief Minister Manish Sisodia has announced that the UT’s oxygen requirement has dipped from 700 MT a day to 582 MT.

Dr Pradip Awate, state surveillance officer for Maharashtra, says Mumbai’s administrative structure is conducive for decentralisation, which may not be easy to replicate in Delhi. “Delhi’s position is more complex because it’s a union territory. So, there tend to be coordination issues between the municipal corporation, the state government and the Centre. Moreover, Delhi is double the size of Mumbai and the housing conditions are worse. If you compare the clusters, you’ll realise that it’s far more congested.”

Dr Sharang Madaan, a resident ICU doctor at Park Group of Hospitals, West Delhi agrees. “We have space to create makeshift hospitals and facilities, but from where do I get skilled medical staff that can operate ventilators? Regular nursing staff is different from that in the ICU. Right now, we need to rope in people from allied healthcare services, AYUSH doctors, homeopaths, Unani practitioners and dentists because their basic foundation and understanding of the anatomy is the same as us. We can train them, so that they can at least operate O2 beds.”

He says the pollution in Delhi only makes matters worse with residents being far more vulnerable to respiratory issues than people in other states.

Although Kakani says the municipality was well equipped when it came to oxygen, complaints of scarcity of beds in the city were all over Twitter last month. Chahal said that these complaints were coming from people, who weren’t following the directives of the war room and trying to reach out to private hospitals directly. “All allotment of hospital beds shall be through 24 war rooms only. Let the name come to us in our list from labs at midnight, and we will go to their homes with beds early next morning, as we are doing since last June,” he said in a statement.

On May 21, 2020, the state had assumed control of 80 per cent of beds in private hospitals. This allowed state and local administrations to control treatment charges in private hospitals, which experts say ensured quality treatment was accessible to people at affordable costs. Hospitals in Mumbai, however, protested as they were reportedly suffering losses, with some Covid-19 beds going empty during the lean period.

Joy Chakraborty, COO, PD Hinduja Hospital & MRC, believes the 80:20 model wasn’t the sole reason for this. “A significant portion of non-Covid-19 patients started deferring their treatments, thinking hospitals may not be the safest place. At least this was the case till more awareness and education made people open to seeking treatment. Segregating beds wasn’t so much of a challenge for us, since we have two demarcated facilities for Covid-19 and non-Covid-19 patients. But for smaller hospitals, this would have been an issue.”

To counter the surge, all Mumbai labs testing samples for Coronavirus have been directed to ensure a turnaround time of 24 hours. State guidelines also mandate negative RT-PCR tests for those working in public transportation, home delivery services, film shoots, and roadside eateries, among other categories. This reportedly led to a surge that created a backlog in several testing laboratories in Mumbai.

Suburban Diagnostics, headquartered in Mumbai, received thrice the number of samples they were equipped to handle in the first two weeks of April.

“Due to the sudden spike, we faced a shortage of testing kits. So, we had to enhance our capacity to maintain the desired turnaround time of report delivery. However, we could clear this path with the help of our team and vendors and are now back on track,” says Dr Anupa Dixit, lab director. Today, they have a capacity of processing 14,000 tests per day and are reporting RT PCR tests in 24 hours.

With news of fabricated Covid-19 reports being in circulation across the country, they have also implemented a QR code system, which they claim will provide authorities ease of access and authentication. The QR code when scanned on a smartphone will instantly show the authenticity of a report from the company’s portal. Any manipulation in the report will be flashed on the system, along with the true test date and report status. “Last year, the BMC introduced a system where the positive report was first handed to the BMC, who would then inform the patient. This was due to contact tracing requirement by the local authorities. In case the patients were informed about the positive reports, they would abscond and spread infection,” adds Dixit. Intimation of positive reports continues to be submitted to the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) through a portal that is subsequently shared with the local authorities. Kakani says labs handing over the reports to the BMC ensured that information about all positive cases came to them by midnight. “Whatever Covid-19 tests were conducted on a given day [before 6 pm] at the labs, had to be shared with us on the same day. We would then sift through the list and segregate it ward-wise; the entire process would be conducted in the night. By 7 am, we’d share the list with the respective ward offices, so that they could start calling patients from 8 am onwards and figure whether hospitalisation or home isolation was needed. The report that came to us in the night would be shared with the patient in the morning.”

Dr Rajesh Parikh, author of The Vaccine Book and honorary neuropsychiatrist at the Jaslok Hospital and Research Centre, attributes the state’s current stability to enlightened leadership and the ability to get all hands on board. “CM Uddhav Thackeray listens intently, especially to scientists, and most importantly, he gave strict instructions from day one to please declare the numbers as they are, and that’s happening regardless of how it’s making us look.”

This transparency is something that he says American physician and medical historian Howard Markel highlighted 50 years ago. “He studied pandemics across the world and tried to figure out the one factor, which was different with countries that did well and those that didn’t. What he found was that secrecy had always led to the further spread of the pandemic.” When it comes to the second wave, Dr Parikh believes the most developed countries have made grave mistakes. “The US was in denial and even fudged numbers, but what they got right was the vaccination. They went full throttle. They realised that this is the only way to move forward. Look at Boris Johnson, for instance, who, in the beginning, said you need to depend on herd immunity, which is a euphemism that a lot of people should die and then the situation will even out.” He says it’s only when the UK Prime Minister fell seriously ill and was admitted to the ICU, that he completely changed his position. “He realised it was a wrong approach, so they have also vaccinated a large percentage of their population.” South Korea, he says, harnessed their experience from a previous pandemic like the SARS. India, he adds, has extensive experience dealing with immunisation, because we have conducted successful smallpox and polio vaccination campaigns. For now, Kakani says his biggest challenge is getting citizens to follow COVID-appropriate behaviour.

“When it comes to infrastructure, we can pull all plugs to get the job done. How do I change mindsets? I hope we don’t let our guard down. We may have a third or even a fourth wave.”

No positive report needed

In order to make the system more ‘patient-centric’, the Union Health Ministry last week revised the national policy for admission of Covid-19 positive patients to Covid-19 health facilities. In the revised policy, the government has done away with the requirement of a Covid-19 positive report for hospitalisation. Under the revised rules, no patient will be denied services at a health facility. A suspect case shall be admitted to the suspect ward of Covid-19 Care Centre (CCC), Dedicated Covid-19 Health Centre (DCHC) and Dedicated Covid-19 Hospital (DCH). This system was first adopted by BMC Commissioner IS Chahal in Mumbai last year, where he created a triage segment at hospitals, where anyone suspected of having contracted the virus and didn’t have a report, could get admitted. “Every facility in the city has a triage area for patients who are experiencing symptoms, but do not have a Covid-19 report to show. We did not want to turn away anybody. If the patient was found to be positive later, s/he was shifted to the Covid-19 ward,” says Kakani.

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!